by Gabriela Keller, Leoni Bender, David Haas, Alexander Maxia, Justin Yarga, Roland Akon Wuwih, Haoxuan Xiong

March 7, 2023

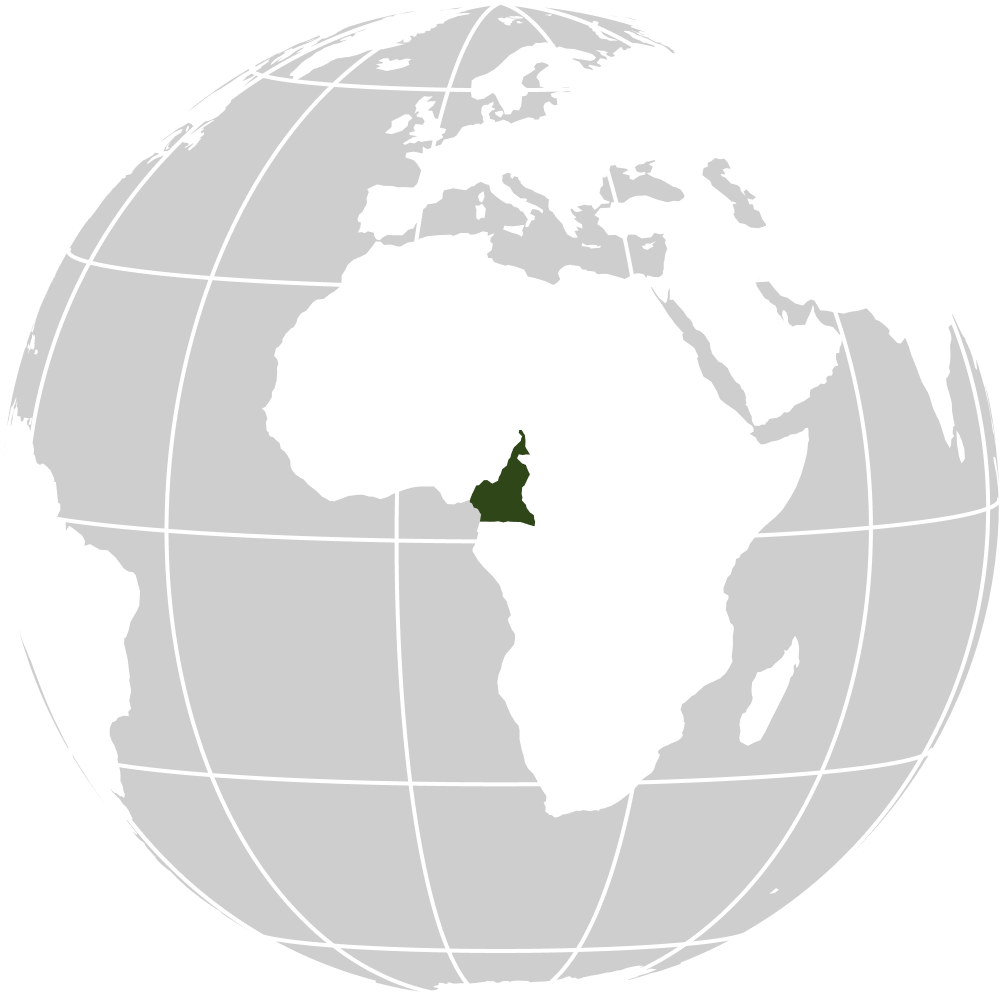

Mud brick huts are scattered along a country road in Cameroon’s South Region. Children sit on the ground in between as a few men make their way through the settlement and into the tropical forest that lies beyond. “This is the land our ancestors left us,” one of them says. “But if natural rubber takes all that away from us, what can we do? What are we supposed to live on?”