The Taliban’s Algorithmic Emirate: How bots can reinforce and shape a political system

How the Taliban use fake identities and bot accounts to simulate support – and exploit the digital space for their propaganda. An investigation into targeted manipulation, virtual control, and the threat to open societies.

It’s now been over three years since the Taliban overthrew the Afghan government and seized control of the country. This has been a time in which women and girls have been denied social participation, independent educational opportunities have been banned, and cultural diversity has been suppressed. The Taliban aim for total control over Afghan society and seek to project an image of strength both domestically and internationally, often employing manipulative digital strategies to achieve this.

These strategies are sometimes presented under seemingly harmless names. Names such as Hadya Panjshiri, Sumiya Panjshiri, and Farzana Panjshiri, behind which Taliban propaganda is concealed. At a glance, these users appear to be women from Panjshir, a province known as the last bastion of resistance against the Taliban. This is where coordinated manipulation becomes visible.

Panjshir province isn’t a place you associate with Taliban sympathisers, and certainly not female ones. In the Taliban’s takeover of 2021, Panjshir was the last province that fell into the hands of the Taliban So why is this the place where the support for the internationally sanctioned Taliban is growing?

This is where it gets interesting: user accounts that appear to be grassroots support are, in fact, part of a tightly coordinated Taliban digital campaign. Our current research tracked 78 suspicious accounts that reveal how the Taliban is simulating consensus, fabricating identity, and hijacking language to dominate online discourse. The digital space has become a battlefield, and they’re optimising it.

Natural beauty instead of oppositional attack

The investigation began in early 2025 by OSINT investigator and founder of Intel Focus, Qais Alamdar–identifying suspicious user accounts that mimicked bot-like behaviours. Many of whom appeared on keyword searches in Afghanistan’s information space on X (former Twitter), where many of these accounts had similar posts. These posts were copied, pasted and used identical images on their posts. While most of these user profiles had profile pictures, a simple reverse image search, a technique that allows you to find information about an image, reveals that they used publicly available images. The list of user accounts was later analyzed from X. Of an initial 120 suspected bot accounts, 78 were still active. Many of the others had either gone quiet or were suspended. What tied them together? For starters, uniform behaviour: tweet frequency, language, tone, and even how their profiles were built.

Over 70 used “Panjshiri” as a surname, even more strangely, many of these accounts posed as women. In a regime that bans women from tweeting in real life, the Taliban are creating digital women to flood platforms with pro-regime content.

Some accounts tweeted over 70,000 times in under two years. One hit an average of 126 tweets per day. This is not human behaviour, it’s algorithmic noise. Their posts ranged from glorifying Taliban fighters and praising hijab laws to sharing generic photos of Afghan landscapes. But more crucially, they worked in sync. At times, dozens of accounts posted near-identical tweets within minutes of each other.

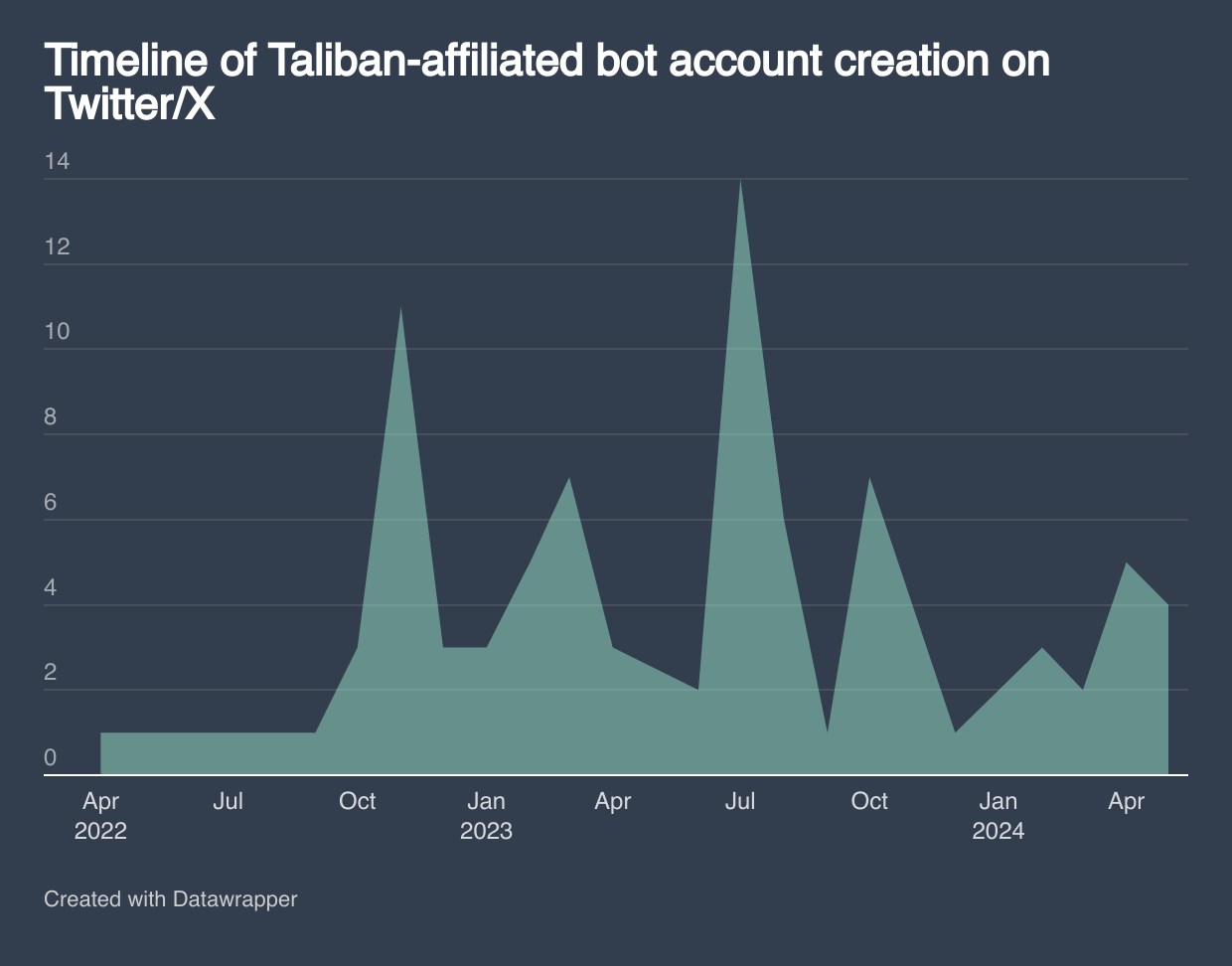

Figure 1: Graph shows the timeline of Taliban-affiliated bot accounts’ creation on X.

Figure 1: Graph shows the timeline of Taliban-affiliated bot accounts’ creation on X.

The timeline doesn’t lie either. Over 60% of these accounts were created within the same six-month period, spanning late 2022 to early 2023. This wasn’t accidental, it was mobilisation.

While bot-like behaviours were identified, definitive attribution of all accounts to coordinated Taliban operations requires further verification, but the patterns are familiar to anyone watching authoritarian playbooks. First comes identity manipulation. By faking Tajik names and female personas, the Taliban seek to present an image of inclusion and support from groups they repress. It’s a digital mask, and they wear it well.

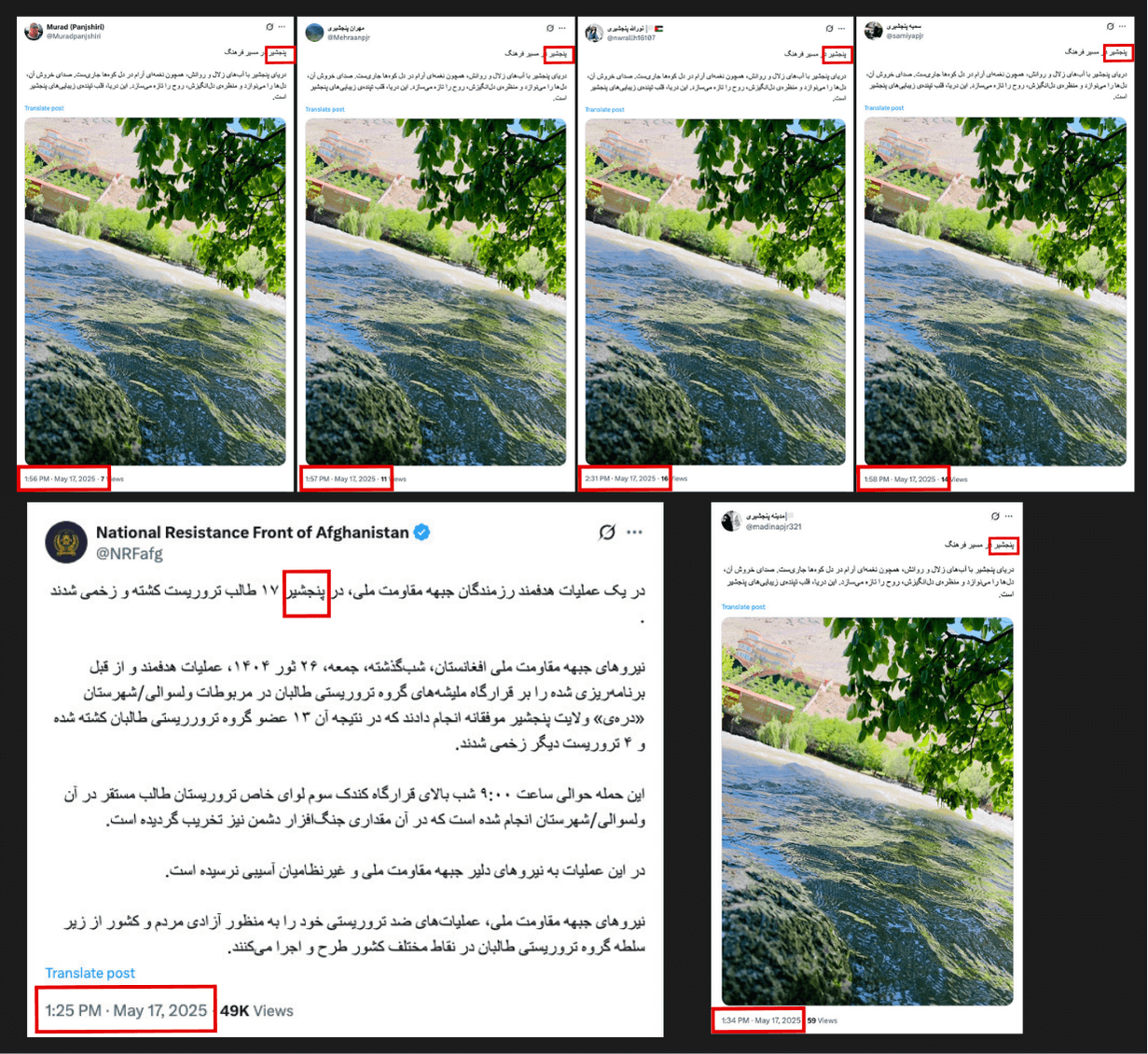

Then comes the hashtag hijack. When the National Resistance Front released a statement attacking Taliban forces, the reaction was instant. Within minutes, bot accounts swarmed the platform with posts about Panjshir’s “natural beauty” or development projects – all tagged with the same keyword. The result? Any search for “Panjshir” led users away from news of the attack and into a carefully constructed mirage.

Figure 2: Coordinated posting of positive content by bot accounts within minutes of National Resistance Front’s critical statement.

Figure 2: Coordinated posting of positive content by bot accounts within minutes of National Resistance Front’s critical statement.

The autocratic playbook goes digital

From Russian disinfo farms to Iranian bot armies, we’ve seen how authoritarian regimes digitalize control. Russia started developing online disinformation campaigns via troll farms in early 2000s, creating false personas to comment on articles in Western media, constructing doppelgangers of well-known websites, dabbling in every topic imaginable, from vaccines to not only US presidential elections, but different electoral processes in 20 countries, including Syria and Libya

And the Taliban’s recent efforts highlight a disturbing evolution. Strategies of information warfare that blend propaganda, identity manipulation, and emotional appeals to shape perceptions both domestically and internationally.

This manipulation has coined a term—the “Algorithmic Emirate”—a virtual state operating within the digital realm. In this new empire, legitimacy isn’t built through votes or diplomacy but through virality, mass engagement, and the suppression of dissent. By mimicking grassroots support, suppressing dissent, and poisoning search results, the Taliban project a version of Afghanistan that fits their vision, one tweet at a time.

Mukhtar Wafayee revealed that Taliban’s “use these accounts to conduct character assassinations of opponents and critics of the Taliban. For instance, these accounts frequently launch coordinated attacks on independent journalists. Many of these profiles are falsely attributed to ethnic groups and regions that have historically shown the strongest opposition to the Taliban, such as Panjshir, Badakhshan, Parwan, Balkh, and Kapisa.”

“They [Taliban’s bot accounts] also spread fabricated narratives about decrees issued by Mullah Hibatullah (Supreme Leader of the Taliban), publishing them with logos of official media outlets to mislead audiences and gain public acceptance,” Wafayee observed. The tactic of using female profile names is also observed by journalists like Wafayee, “to justify and soften the Taliban’s anti-women image,” he adds.

A Paradoxical Digital Identity

It’s a paradox that a regime suppressing women physically and politically now coins digital spaces that seemingly advocate for freedom. These accounts,be it praising revolutionary ideals or lamenting foreign opposition, are artifacts of a sophisticated online strategy. Their goal: to overwrite the complex reality on the ground with targeted, data-driven narratives. This isn’t mere deception; it’s a form of information warfare that seeks to redefine public perception and political legitimacy. Mukhtar Wafayee, an investigative journalist for the Independent Persian, states that, “the Taliban have deliberately launched a wide-ranging campaign through both traditional and online media to gain political and social legitimacy inside and outside Afghanistan,” highlighting the strategies deployed by the Taliban after their takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021. Wafayee claims that “alongside establishing official and traditional media outlets to support their campaign and justify their religious-political narrative, the Taliban have also created dozens of fake accounts on X, TikTok, Facebook, and Instagram.”

Implications Beyond Afghanistan

As authoritarian regimes expand their digital arsenals, the stakes for democracies are enormous. From the US to Europe, misinformation campaigns, bot-driven narratives, and targeted disinformation threaten to undermine democratic processes and erode public trust. This evolving threat underscores the need for vigilant safeguards in democratic countries – Germany is not an exception – that are already grappling with disinformation campaigns.

Are social media platforms and governments prepared to confront these sophisticated forms of manipulation? Or are they unknowingly enabling autocracies by allowing inauthentic voices to dominate digital discourse?

The Taliban have answered. The question is: have we?

Download the full report here.

—————–

Editing: Nora Pohl und Luc Martinon

Fact Checking: Viera Zuborova

Graphics: Qais Alamdar

Communication and Social Media: Katharina Roche