von Lilith Grull und Frida Thurm

17. February 2026

von Lilith Grull und Frida Thurm

17. February 2026

At a glance:

A nurse arrives at a clinic in Freiburg, ready for his first day on the job. He turns up with his suitcase. His new boss, Andreas Bernhard, tells us the situation was immediately clear to him. “The guy was new to the city and didn’t know where to go,” explains Bernhard, Nursing Director at Artemed clinics. The apartment promised to him was now no longer available. Affordable alternatives seemed impossible to find. Although the nurse had a secure job, for all intents and purposes he was homeless.

Rents and property purchase prices have risen so sharply in the EU that even essential workers can no longer afford housing in many places: between 2015 and 2025, rents in the EU soared by an average of 21.1 percent, while purchase prices rose by as much as 63.6 percent – with considerable differences between regions. In major German cities, rents have risen by around 50 percent in the past decade.

First European-wide analysis of local housing prices

An analysis by CORRECTIV.Europe reveals, for the first time, the extent of the housing shortage across the EU on a local scale – based on the example of nurses. We collated their incomes and combined these with data from the ESPON House4All research project, which determined average asking rents and purchase prices in almost 100,000 cities and municipalities throughout the EU between March 2024 and March 2025. In the final report, the researchers concluded that people new to the housing market are especially hard hit. And they warn that the current situation is just a preview of an even more dire affordability crisis.

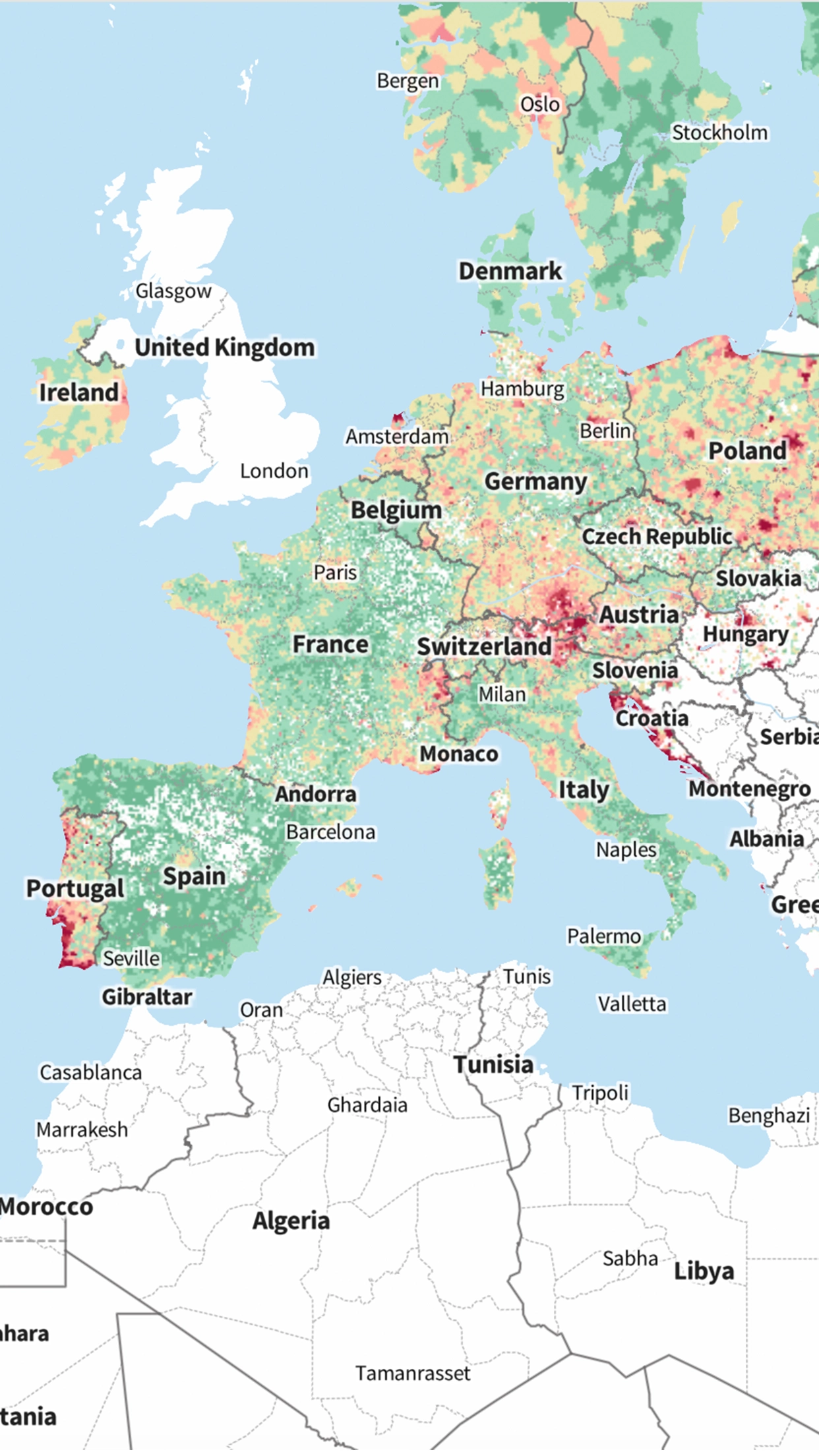

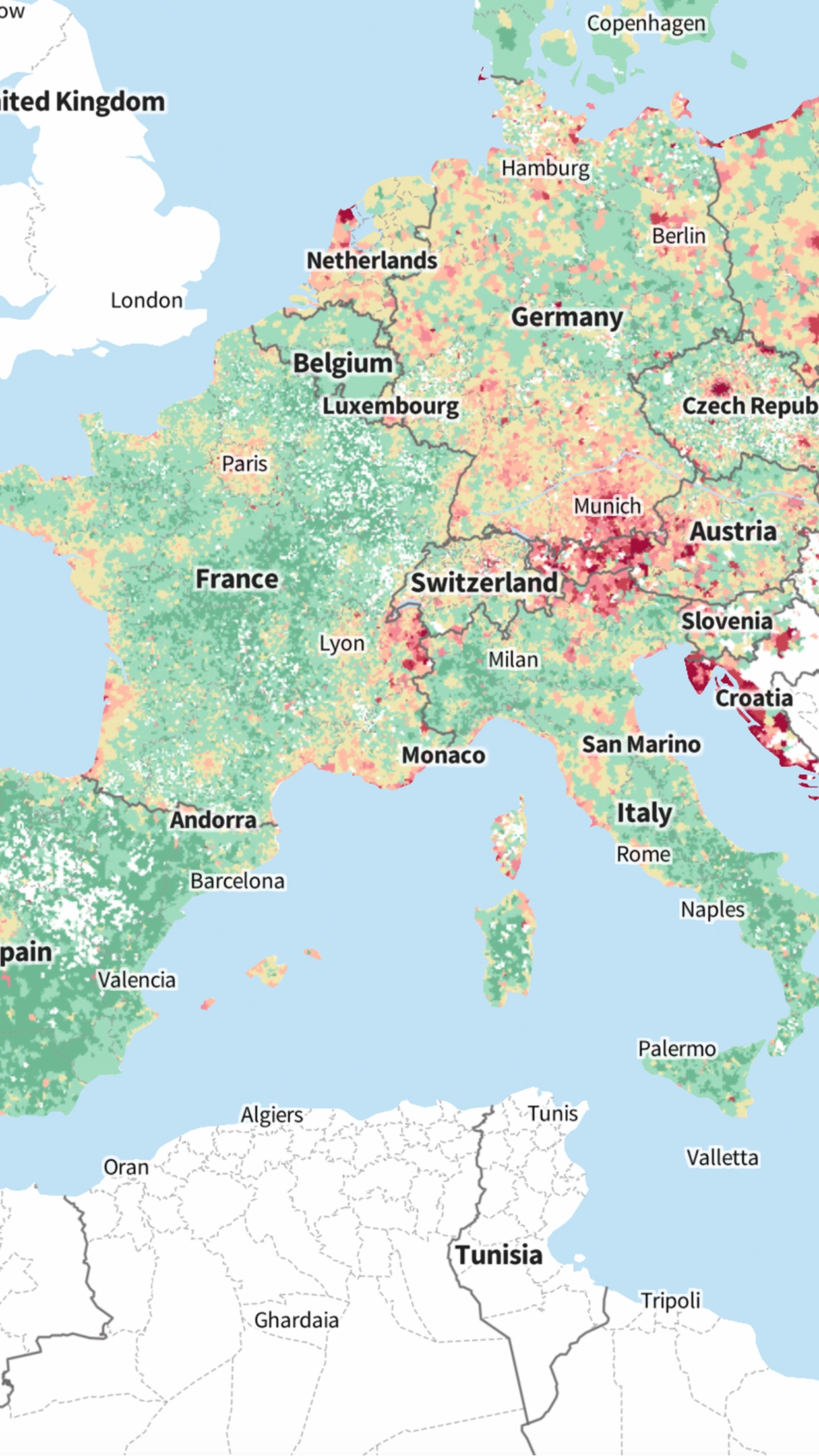

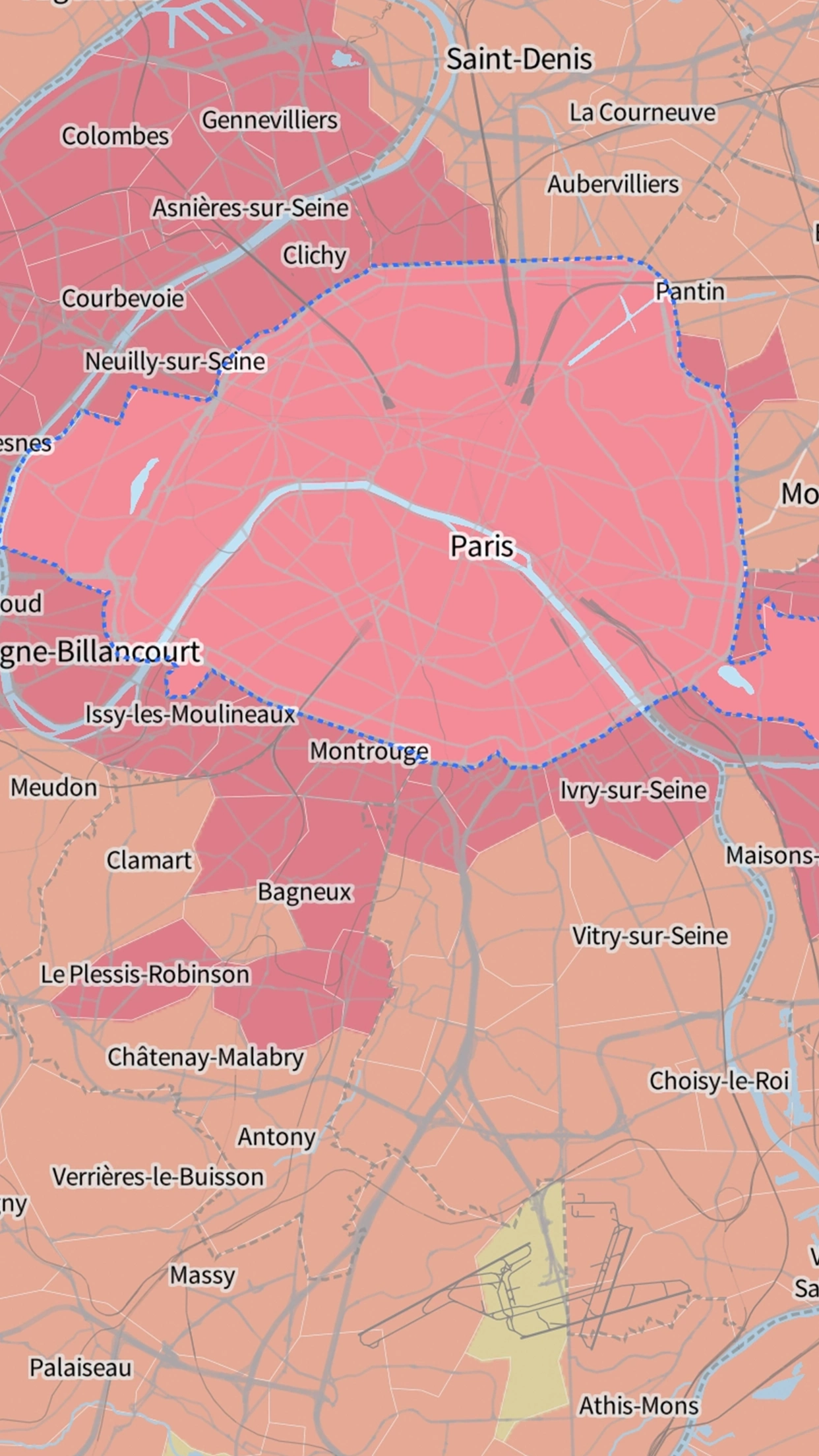

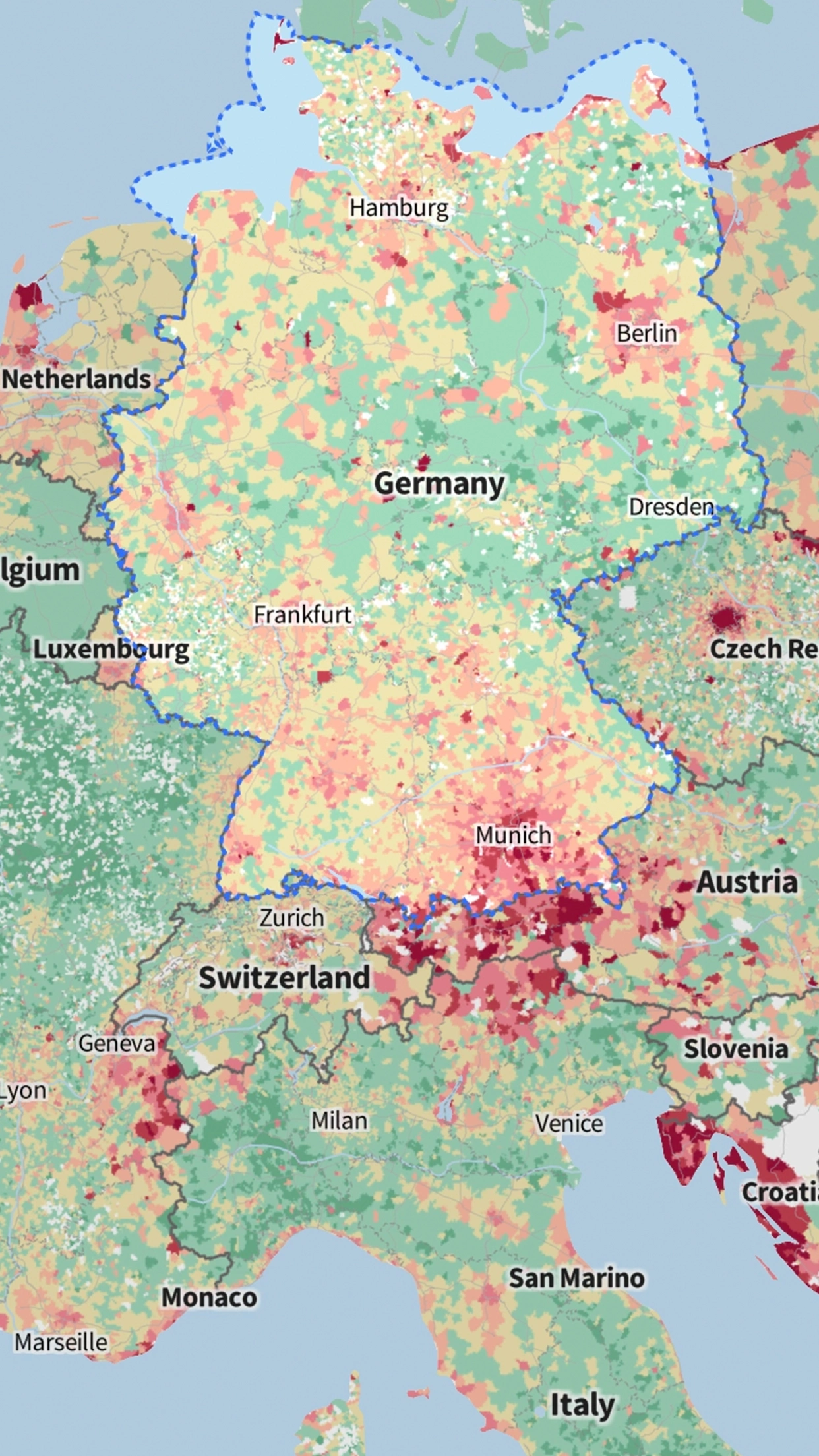

Our analysis shows that in more than 15 percent of the localities in the EU, Norway, Iceland and Switzerland, the average salary of professional nurses is not sufficient to rent or purchase a 45-square metre apartment. These cities and municipalities are marked in red on the map. Property purchase prices are important since most people in Europe own the apartment or house in which they live.

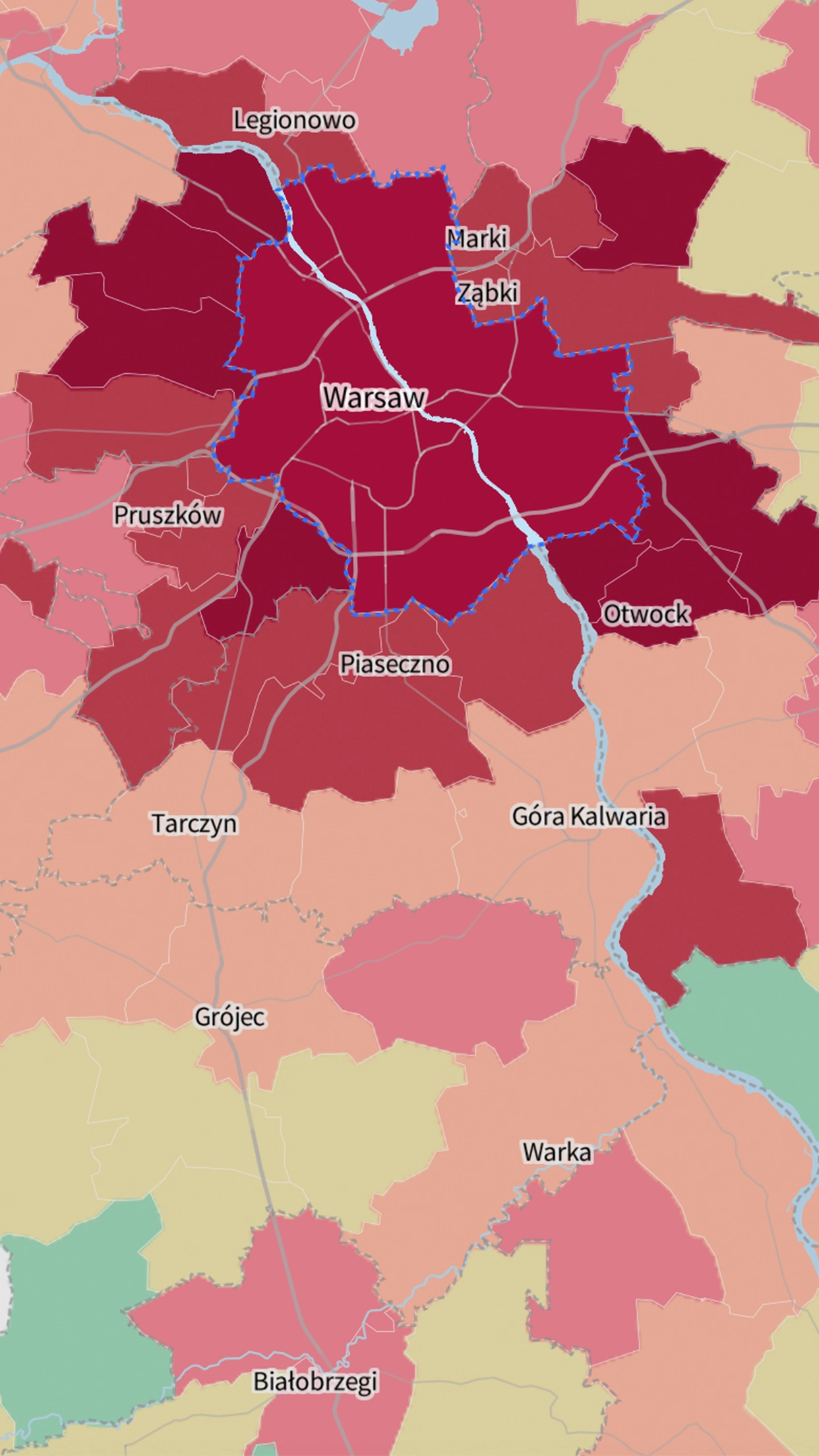

Nurses have a particularly hard time in large cities – such as Warsaw, where the monthly mortgage instalment would cost more than 70 percent of their average net salary.

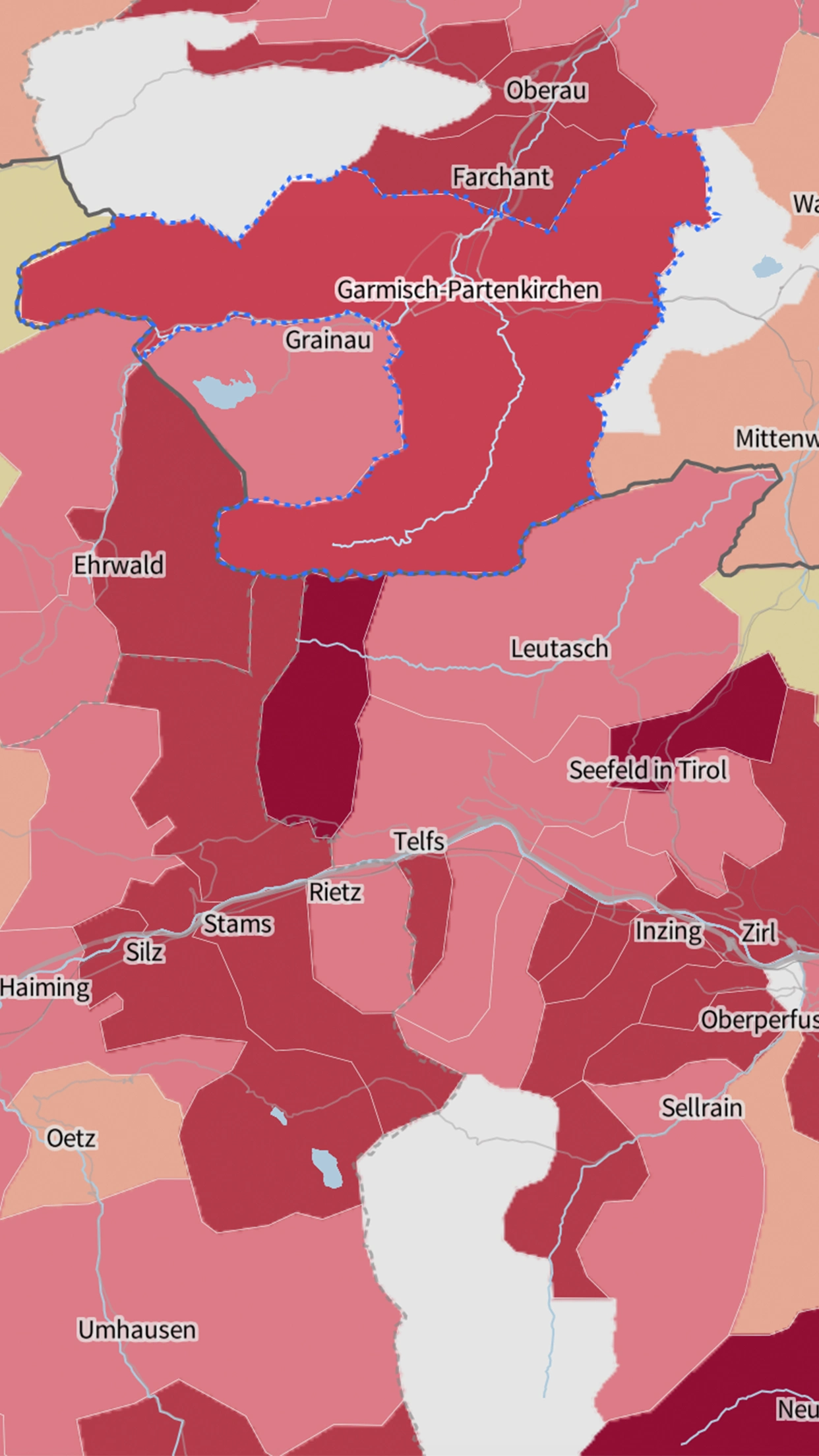

Typical holiday destinations are also particularly expensive – for example in the mountains or by the sea. In Garmisch-Partenkirchen, a winter sports resort, current property purchase prices would consume more than half of a nurse salary.

Significantly more people are affected by the high prices than it seems at first glance. Because many of the affordable regions are quite sparsely populated, whereas expensive areas are more densely populated: more than one-third of EU inhabitants live in places where purchasing a small apartment is not possible on a nurse salary.

Is renting a solution if purchasing is too expensive? The map for rental apartments contains less dark red than the map for purchasing. There are fewer extremely expensive areas as far as rentals are concerned. Nevertheless, more than 15 percent of cities and municipalities remain unaffordable for professional nurses.

In Paris, the outlook for nurses is grim: more than 45 percent of their salary would go towards renting a small apartment – considerably more than the 30 percent threshold that is still considered affordable.

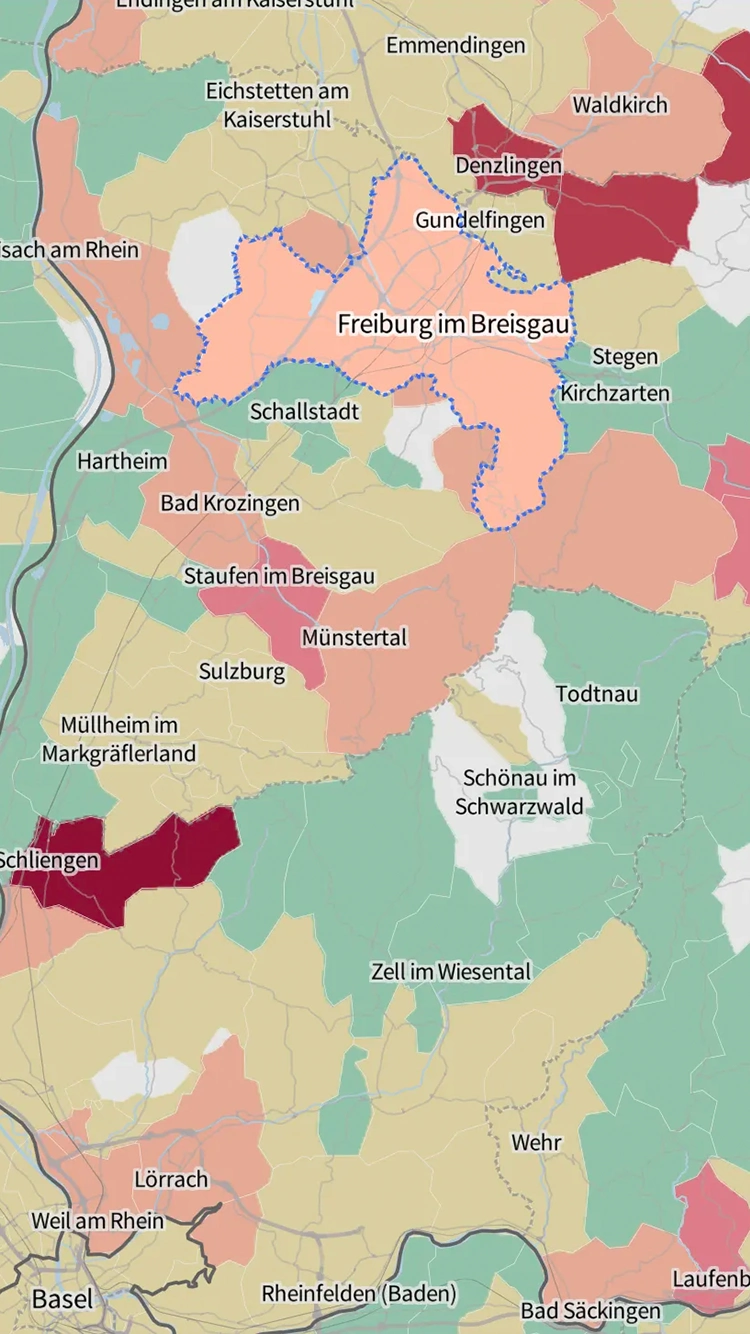

In Germany, the crisis is evident in the south and in the metropolitan regions. In seven of the ten largest cities, average asking rents are not affordable on nurse salaries. These cities, of course, also urgently require nurses.

The average asking rent in Freiburg also exceeds the 30 percent threshold.

This analysis is based on the House4All project by the European research programme ESPON. Details about their methodology can be found here. The House4All project constitutes an unprecedented source of data on housing prices. They scraped online rental and sale listings across Europe weekly from March 2024 to March 2025. Data from over 100 million listings was compiled, cleaned and aggregated according to LAU (local administrative unit; representing municipalities in most EU member states).

The rental data concerns private rentals advertised online and does not include social housing or non-profit rentals. Furnished or serviced apartments may be included, however. The data is therefore not representative of the entire rental market; instead, it conveys an idea of what people face when searching for a new home without a property agent, on an online platform and without any reliance on personal recommendations, contacts or waiting lists. Similarly, the sales data does not include offers that were not listed on online platforms.

Additional costs have been added by ESPON to the available price information from the listings if they were deemed a mandatory component regarding the housing transaction. Thus, if applicable, taxes or land registry fees have been added to the available sale prices. For rentals, no additional utility costs were added on top of the rentals listed. However, dependent on the context specific listing standard, some listed prices may nonetheless contain a mandatory utility component.

Regarding outliers, we discarded some unexpectedly high values from the House4All project based on the number of listings obtained in each municipality and the divergence of the values in comparison with neighbouring municipalities.

CORRECTIV.Europe supplemented the House4All data by investigating the situation of nurses and whether they can afford to purchase or rent a 45-square metre apartment. To do this, we gathered data on nurses’ salaries by asking each national statistical office for the national and/or regional averages.

We used regional-level data where available. Otherwise, we used national data either provided by the national statistical offices or obtained from this OECD dataset. We used Eurostat’s average tax rates datasetto calculate salaries after income tax and https://www.exchange-rates.org as a source of historical exchange rates to convert all values to euros. In determining affordability of renting an apartment, we deemed any amount up to 30 percent of the net salary as affordable. This 30 percent threshold is widely used as a rule of thumb and, in the absence of a more precise measurement, has been considered a stable indicator of affordability by scientists at Harvard University. To calculate affordability of purchasing an apartment for nurses, we used the same methodology as House4All: mortgage instalments from their dataset and the same formula to calculate monthly repayment rates on a 30-year mortgage.

The average floor space per capita in the EU is just shy of 40 square metres. For this reason, we chose to focus on the second of the four apartment size groups analysed by ESPON (25, 45, 75 and 100 square metres). Where available, we used the price per square metre provided in the ESPON data for apartments from the 45 square metre group (which contains data for homes of between 30 and 60 square metres) in each LAU. For LAUs where this value was unavailable, we used the average price per square metre for all apartments and adjusted it using the national average price differential between 45-square-metre apartments and the overall apartment stock.

Limitations:

Price data: The data gathered by ESPON is not representative of all sales prices or rents currently paid in the EU/EFTA countries. It instead conveys an idea of the situation someone would likely face when searching for a new home online and with no access to informal networks.

Nurse’s income data: We worked with average and median salaries; individual salaries can differ. To the greatest possible extent, we aimed to compile data on local scale. However, some countries collect data only at the national level, and others do not even provide national income data. In some cases, nurses and midwifes are grouped together in the income data. We relied on an OECD dataset where national data was unavailable. We could not attain any income data for Cyprus, Romania, Liechtenstein or Malta and therefore cannot provide affordability data for these countries.

Nurses serve as an indicator of where things have gone wrong on the housing market: in the context of this research, they are representative of people in professions that are essential for society. No place could function without them, yet there are many places where they can no longer afford to live. In Germany, the median gross monthly salary of nurses is 4,329 euros, which is almost identical to the median salary of the entire population. This means that where nurses cannot afford to live, society’s middle-income earners also cannot.

“The housing shortage is very clearly putting us under pressure when it comes to recruiting professionals,” says Nursing Director Bernhard. The clinic recruits professional nurses and trainees throughout Germany and internationally. Bernhard ensures they have accommodation in Freiburg. Almost half of the staff meanwhile live in apartments or rooms that are rented or at least arranged by the clinic itself. Nevertheless, extreme cases still turn up at his office now and then: employees who cannot find an apartment at all.

Unaffordable housing has meanwhile become a problem for the economy in Europe: “The EU’s housing crisis hampers competitiveness and economic growth” warn experts from the European Policy Centre. “Young professionals struggle to afford urban housing, leading to talent shortages in key cities and stalling business growth and innovation.”

This burdens not only those looking for housing, but also employers: in some countries, the offer of affordable housing has long served as a political tool enabling the economy to pay mid-range wages and salaries, says Franziska Sielker, professor at TU Wien and head of research at ESPON’s House4All project. “But if rents continue to rise, employees will also demand more money, putting more pressure on the entire economy.”

It starts with land prices. Land is limited, and in many places demand outweighs supply. This is exacerbated by the growing proportion of institutional property investors in the market, which – according to an analysis by the European Central Bank – is decoupling demand from local incomes.

In addition, more and more people are moving to cities where too little is being built to meet demand. A growing market for short-term rentals, a lengthy period of low interest rates and an increase in the prevalence of single-person households have also made housing more expensive. Furthermore, a study by the University of Trier proved that money laundering also increases property prices. The reason: criminals are prepared to pay above market value.

Then there are utility costs. An analysis by CORRECTIV.Europe shows that 47 million Europeans were unable to afford adequate heating in 2023.

High demand and limited supply have caused an increase in property rents and purchase prices in many cities. The most significant reasons are:

A paper by the European Central Bank (ECB) found that purchases of residential properties by institutional investors have tripled in the last decade. It also found that, when institutional investors intensify their purchasing of residential real estate, house prices rise and remain elevated for an extended period. According to the ECB, this is because these investors often buy in bulk, which increases demand and pushes prices up. Hence, when institutional investors move in, purchasing a house or apartment becomes more expensive.

These findings are supported by an economic analysis for Empirica. Kholodilin also highlights the effect of fiscal policies: In most cases, higher taxes (such as property tax, vacancy tax, foreign buyer tax or transfer tax) lead to lower prices. The same applies to monetary policy, according to Kholodilin: lower interest rates lead to higher prices, although unlike higher taxes, these also lead to increased building activity.

Affordable housing is now frequently described in politics and science as the social issue of the 21st century. After all, a secure roof over one’s head is a prerequisite for many things that contribute to a fulfilling life: good education, stable relationships, sufficient financial resources in old age.

There have been protests in various European cities against unaffordable rents. In view of the crisis, the United Nations reminded the EU in a report in 2024 that housing is a human right – and called for the instigation of countermeasures.

According to estimates, more than one million people in the EU are homeless, and in many member states these numbers are rising. In the most extreme cases, those affected sleep on the streets. And this despite the aim to end homelessness by 2030. In Germany, the problem is also manifesting in the growing number of evictions: people unable to pay their rent are even evicted by bailiffs in extreme cases.

“The lack of affordable housing is leading to people postponing their life goals. This generates much frustration and fear in society.”

Scientist Franziska Sielker

“The lack of affordable housing is leading to people postponing their life goals,” says researcher Sielker. “Moving in together, starting a family, taking on a new job in another city.” Many young people are now living with their parents for longer, and commuting to other cities for study, for example. Those who can afford to buy property are often still paying it off in retirement – leading to uncertainty about how to finance this phase in life. “This all generates much frustration and fear in society.”

High housing costs exacerbate economic and regional inequalities. This is the conclusion of the analysis carried out by the European Policy Centre. The housing crisis poses a “threat to the EU’s priority on democracy, as citizens strongly link the legitimacy of political systems with the economic outcomes they deliver.”

Economic researcher Konstantin Kholodilin from the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) analysed in a meta-study of 886 empirical studies how government regulations impact the housing market. Most measures have side effects, making it difficult to identify a single best or most effective instrument, he says. Rent control measures in Berlin, for example, have led to rising rents for new builds. Kholodilin advocates for a mix of different approaches – and for their coordination. He identifies housing allowances as particularly effective. Another DIW study shows that social housing, while expensive, can be particularly effective in alleviating the situation.

Kholodilin believes action at the local level is crucial for tackling the housing crisis, because it is closest to the problem: “Cities have considerable say when it comes to regulating property misuse or short-term rentals, protecting neighbourhood character, and allocating plots of land,” he says. “They can also require developers to set aside a proportion of new housing for social use – in cities like Berlin and Munich, that proportion can be as high as 30 percent.”

But because land prices have been proved to significantly impact property prices and therefore rents, economists have also come up with very foundational ideas to counteract this. Dirk Löhr, a professor of economics at Trier University of Applied Sciences, is in favour of a land value tax. This would enable the state, and therefore society, to benefit from the increase in land values to which owners generally do not contribute much. In parallel, it would lessen speculative interest in land as an investment.

Besides classic notions such as building more, capping rents, preventing empty housing and supporting lower income earners, there are also new proposals. Spain, for example, is planning a 100 percent tax on property purchases made from outside the EU. Finnish think tank Demos Helsinki is campaigning for incentives to swap homes: those who need less space in old age could free up space for families. Shared flats could also be part of the solution.

EU Commissioner for Housing Dan Jørgensen also sees insecurities in connection with housing as a risk to democracy in Europe. In December 2025, the EU Commission presented the first “European affordable housing plan”. Its main aim is to stimulate investment in housing construction by means of lower legal hurdles, additional EU funding and an investment platform.

In Freiburg, Director of Nursing Bernhard has already taken an extraordinary measure to avoid a major crisis for his organisation: the clinic has hired a property agent. A residence hall and rented apartments have also been secured for the company’s trainees. The new nurse who arrived in Bernhard’s office with his suitcase actually had to stay in a hotel initially. Until an apartment unexpectedly became available: another employee who became homesick during his probationary period decided to leave Freiburg.

As other nursing institutions are facing similar problems, 16 of them have banded together with help from the city of Freiburg to form an initiative: private property owners can offer their apartments directly to clinics and nursing institutions. According to the institutions involved, 160 apartments have already been offered and tenants already found for 40. Such intensive and free support in the search for accommodation is the exception, however.

“If the housing issue is not resolved, other problems will be exacerbated,” warns researcher Sielker. The more urgent the need for new buildings, the greater the risk that other goals intended to future-proof cities could remain unfulfilled: more sustainable urban planning, less sealing and heat islands. Sielker fears that even major social goals will be discarded if people are dissatisfied. Housing, therefore, is an essential foundation of a functioning society. The example of nurses shows that this foundation is under threat in much of Europe.