Influence operation exposed: How Russia meddles in Germany’s election campaign

A CORRECTIV investigation has uncovered that a Russian disinformation campaign established around 100 fake websites ahead of Germany’s general election. Their purpose: to influence the election campaign due to take place in February. In several cases, these sites have already been used to discredit German politicians.

This article was first published in German on January 23 here.

A Russian influence operation that previously targeted the US has set up over 100 websites with the help of AI to spread disinformation and meddle in Germany’s upcoming elections, an investigation by CORRECTIV has found.

Over the past months, the campaign has created and disseminated false claims about German politicians using AI and deepfake technology. These disinformation narratives were then spread via a network of fake news sites. For example, in a false article and video, Green party candidate Robert Habeck was accused of having abused a young woman years ago. Other baseless claims promoted by the campaign were that foreign minister Annalena Baerbock met with a gigolo during trips to Africa, or that Marcus Faber, head of Germany’s parliamentary defence committee, is a Russian agent. Other fake news stories claimed that the German military plans to mobilise 500,000 men for an operation in Eastern Europe, and that Germany signed a migration agreement to bring 1.9 million Kenyans to Germany.

According to CORRECTIV’s investigation, these false claims are part of a Russian operation known as “Storm-1516,” whose aim is to influence the upcoming general elections in Germany. “Storm-1516” appears to have been interfering in the election campaign for at least the last three months. It appears to be linked to a former U.S. police officer, the notorious Russian troll factory Internet Research Agency (IRA), and Russia’s military intelligence agency, the GRU. The U.S. government has already sanctioned some of those alleged to be responsible for the campaign’s meddling in the elections there.

Germany’s Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution warned in November of possible attempts by foreign states to influence the 2025 general election. At that time, preparations in Moscow for such interference appear to have been well underway. CORRECTIV’s reporting shows that following the collapse of Germany’s coalition government and the announcement of snap elections, the disinformation campaign quickly shifted its focus to Germany.

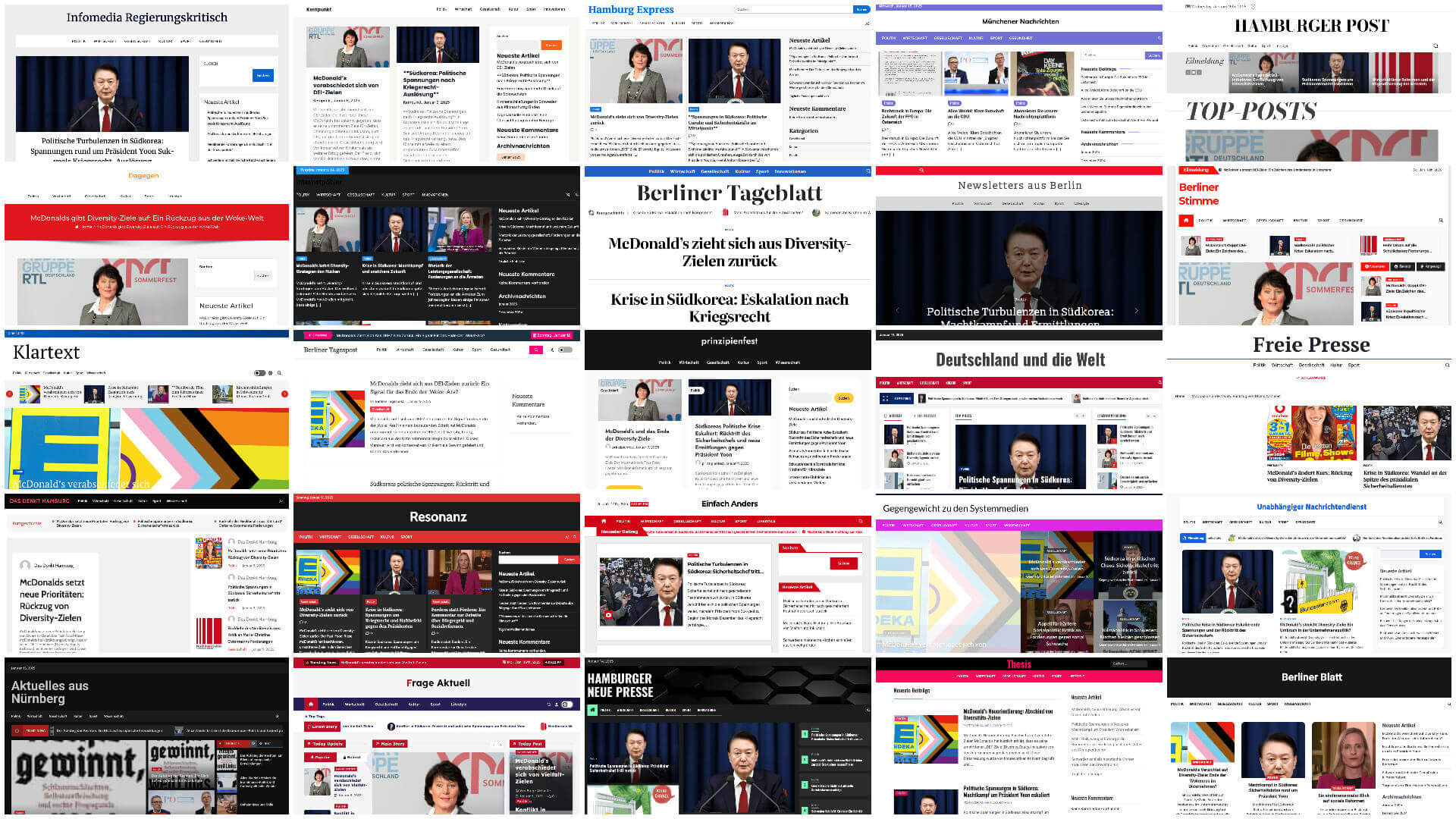

Working in partnership with Newsguard and the investigative project Gnida, CORRECTIV has uncovered the network of more than 100 German-language websites. Many of them have not yet been used to spread fake news but appear to have been set up in advance, waiting for activation. Once activated, the fake news stories published on the sites are spread by pro-Russian influencers in Germany. According to experts, this makes “Storm-1516” more effective at reaching audiences than other disinformation campaigns, such as the ongoing Russian “Doppelganger” campaign.

U.S. elections interference: ex-cop spread fake news stories about Kamala Harris and Tim Walz

To better understand Russia’s intentions for Germany, it helps to look at its actions in the 2024 U.S. election. Starting in the summer of 2024, “Storm-1516” targeted the U.S. presidential elections with the apparent goal of securing a victory for Donald Trump. Before that, the campaign had already circulated false claims about Ukraine and the Olympics.

In September, the Russian influence operation produced a fake video in which a woman claims she was injured as a child by Kamala Harris in a hit-and-run car accident back in 2011, leaving her in a wheelchair. In October, fabricated sexual abuse allegations were made against Harris’ running mate, Tim Walz.

The same tactics used in the U.S. are now being deployed in Germany: videos are being created with actors or deepfake technology, showing supposed whistleblowers or witnesses. These videos serve as the basis for false reports published on one or more of the campaign’s fake news sites. For example, the Harris video was attributed to a fictitious local media outlet in San Francisco. The story was then disseminated via a network of seemingly independent influencers on platforms like X and Telegram.

John Mark Dougan, a former Florida police officer now residing in Moscow in Russia, is responsible for the dozens of fake news websites in the US, according to reports by media outlets and analysts. He allegedly sets up the websites and fills them with rewritten articles using AI tools. Later, individual custom-made fake news stories are added to the sites. In doing so, Dougan plays a central role in spreading the pro-Russian propaganda.

Suspected ties to Russia’s GRU intelligence agency

Russian documents obtained by a European intelligence agency indicate that Dougan’s operation is funded by a GRU agent, according to a Washington Post report. Likely describing the same operation, the U.S. Treasury said in a December 2024 press release that “at the direction of, and with financial support from, the GRU,” AI tools were used “to quickly create disinformation that would be distributed across a massive network of websites designed to imitate legitimate news outlets.”

The method proved successful for the campaign: its videos have garnered millions of views, according to analysis by NewsGuard. Prominent politicians, such as the new vice president J.D. Vance and Republican Marjorie Taylor Greene have spread “Storm-1516″’s narratives. By using influencers, the campaign is significantly more effective than, for example, the Doppelganger campaign – another Russian disinformation campaign that is still ogoing – said Darren Linvill from Clemson University, who has been monitoring the campaign. “Storm 15-16’s engagement on some of these stories is just astounding.”

Reporting by CORRECTIV and NewsGuard into the technical methods behind the campaign suggests that the same network behind the English-language websites in the US may also be responsible for the German-language websites that have now appeared. When asked for comment, Dougan denied any connection to the GRU or any other Russian government entities. In a Whatsapp message he called the Russian government as “a bunch of idiot bureaucrats who never get anything done” and said he “wouldn’t have that kind of patience”. He did not respond to more detailed questions about the websites and his involvement in the campaign.

From one election to the next: more than 90 disinformation websites ready and waiting for deployment in Germany

In November 2024, as German president Frank-Walter Steinmeier announced snap elections, the Russian disinformation campaign shifted its focus towards Germany.

But even before November, Moscow had been meddling in German politics. In summer 2024, “Storm-1516” had produced several individual fake news stories targeting Germany. For example, in July 2024, a claim surfaced that a pig’s head wrapped in a Palestine flag with the inscription “Ukraine stands for Israel” was thrown into a Berlin mosque. This appeared on a portal called the “Berliner Wochenzeitung,” a publication that does not exist.

The fake news story alleging that Annalena Baerbock had an affair with a gigolo appeared in August on a site called “Zeitgeschenen” (which contains a typo in the name). A not previously reported deepfake video aimed at discrediting FDP defence politician Marcus Faber shows a supposed former colleague accusing him of being a Russian agent. An article referring to the video appeared on a site called “Andere Meinung.” Perhaps because it was released the day before the collapse of the government coalition in November, the case received little attention.

Shortly after this the network really started to gain momentum. Since November 19, 2024, the people behind the Russian operation have set up at least 99 additional domains in three waves of activity. Together with the Gnida Project, CORRECTIV identified the websites based on different technical characteristics. They have names such as “Scheinwerfer” (Spotlight), “Widerhall” (Echo), “Wochenüberblick aus Berlin” (Weekly Overview from Berlin), or “Unabhängiger Nachrichtendienst” (Independent News Service).

The Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution, Germany’s domestic intelligence service, declined to comment on the campaign. However, a spokesperson stated that “the registration of subject-specific domains in preparation for individual disinformation campaigns is in line with known tactics of Russian influence operatives.”

“These [websites] are clearly consistent with Storm 1516 websites,” said Darren Linvill, the professor from Clemson University. CORRECTIV showed him some of the German-language websites. „They are using off the shelf content creation tools, they’re stealing content from legitimate news sources in a very consistent way, and all of them have certain similarities in that content,“ he said, adding that there are also similarities in the distribution network.

A large portion of the sites are already being filled with content, with only a few sites still entirely empty. While the content doesn’t always contain outright fakes, it is far from neutral. According to analyses conducted by Newsguard, the content comes from right-wing media outlets like Compact and Philosophia Perennis, or pro-Russian blogs like Nachdenkseiten and the German arm of Russia’s state-controlled RT news channel. According to Newsguard the articles were modified using AI. This is the same method that the former police officer Dougan used in the US.

The websites show that the campaign is gearing up ahead of the Bundestag election. And a recent example clearly illustrates the kind of disinformation that may still be spread during election campaign.

Agitation with a supposed German ‘migration agreement’ with Kenya

On December 19, 2024, a piece of disinformation was published on the website Presseneu alongside the other automatically generated content. It concerned a so-called ‘migration agreement’ between Germany and Kenya that had supposedly been signed a few months before.

The article clearly aimed to provoke emotions, with the headline: “Germany plans to import 1.9 million Kenyan workers: A new migration crisis on the horizon?” The figures cited are completely unrealistic. The text references two articles from established African media outlets as sources: the Kenyan portal Tuko and the South African The South African.

However, both are sponsored content – someone paid for their publication. But who? Tuko did not respond to enquiries. According to The South African, the site received 12,000 South African Rand for the article, roughly 620 Euros. The portal didn’t disclose the client’s contact information, but after some time, an supposed intermediary reached out to CORRECTIV. He claimed he paid for the article “as part of a larger paid campaign.” Who was his client? No answer.

The two ‘sources’ were clearly meant to enhance the credibility of the Presseneu report– this tactic is known as “information laundering.” A very similar tactic was used with the Baerbock-Gigolo story, where the source was an advertisement in the Nigerian Daily Post.

A few hours after publication, the Presseneu article was being spread on X and Telegram – sometimes by influencers with a large following.

Right-wing, pro-Russian influencers share the fake news stories conspicuously early

The dissemination of fake content using real people is another characteristic of the “Storm-1516” campaign. The inclusion of influencers is a “proven modus operandi, particularly of Russian influence actors” according to Germany’s domestic intelligence service. It is therefore possible that these actors would “engage in similar activities ahead of the general election,” the office said in a response to CORRECTIV. And indeed, as the disinformation campaign focused on Germany, more and more German-speaking, pro-Russian influencers joined in.

It is striking that it is often the same individuals who are first to spread the fake narratives. Among them are Michael Wittwer, a former candidate for the far-right party Pro Chemnitz, Jovica Jović, a pro-Russian activist, and Alina Lipp, a pro-Russian influencer who runs a Telegram channel with over 180,000 subscribers. Their posts are often shared by Alena Dirksen, who was recently the owner of a Russian restaurant in Mittweida.

It is unknown whether these influencers are paid to spread the disinformation. A case from the U.S. election campaign showed that money was indeed involved: in an interview with CNN, X user @AlphaFox78, a Trump supporter with hundreds of thousands of followers, claimed he had received $100 on several occasions to spread videos and memes. The money came from Simeon Boikov, a pro-Russian propagandist from Australia, known online as AussieCossack.

Boikov also spread false information targeting Germany. He was among the first to post the Baerbock fake on X and also shared the fake story about the pig’s head.

A German right-wing influencer, operating under the pseudonym “Ganesha” on X, hinted at a similar situation in early December: he claimed to have turned down “an offer from a patriotic shop” to post paid advertisements and added that he thereby didn’t share “something that was almost certainly fake news.” He was referring to the Habeck fake. A few days later, “Ganesha” shared the Presseneu article about the immigration agreement with Kenya and wrote: “P.S. Sponsored post, neither Putin, Mossad, nor Trump paid me.” He didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Asked for comment by CORRECTIV, both Jović and Dirksen denied having been offered money for spreading the content. However, Dirksen says: “I wouldn’t be surprised if something like that does happen.”

A foundation functions as a hub for pro-Russian influencers

There is another common element among the influencers: they are all connected to the Russian “Foundation to Battle Injustice” (FBI). This is a platform that aims to highlight alleged injustices in Western countries. The foundation also has a German branch.

Jović and Lipp are quoted in articles on the foundation’s website. However, according to Jović, this was not voluntary – a video embedded in an article there originally came from his own Telegram group and was edited, he claims. He has distanced himself from the foundation, Jović said. Alina Lipp did not respond to our enquiries. Dirksen and Wittwer have repeatedly shared German-language articles from the FBI on their networks, but also failed to respond to our enquiries.

Why is this foundation relevant? It was founded by the former head of the notorious Internet Research Agency (IRA) troll farm, Yevgeny Prigozhin. Following his death in June 2023, part of this apparatus is believed to have started working in the “Storm-1516” campaign. This conclusion comes from Microsoft’s Threat Analysis Center, according to the New York Times. Professor Darren Linvill also sees parallels. He describes the mission of the “Foundation to Battle Injustice” as “the global recruitment of influencers for the purpose of spreading disinformation as opposed to propaganda.”

Leaving an impression regardless of credibility

This campaign to interfere in the German elections that we have exposed shows us that the threat of Russian disinformation is real. By discrediting individual politicians, Moscow is attempting to influence the outcome of the German election in February. Sometimes the attempts seem clumsy. It’s not very plausible, for example, that the FDP politician Marcus Faber, a staunch supporter of Ukraine, is a Russian agent. “I would have expected more sophistication from Russian propaganda,” Faber commented to CORRECTIV.

But no matter how credible they are, these narratives are stubbornly repeated, and there appear to be hardly any suitable countermeasures so far. Posts about the Baerbock fake are still circulating on X. The fact that it has now been debunked seems irrelevant. The main aim is to keep the rumour alive.

The technology behind our investigation

The starting point of our investigation was the fake news story about the migration agreement with Kenya, which was spread in December. Because the website presseneu.de was still online, we were able to examine its technical features and found that the same server hosted two other websites. These websites were similarly structured, but had not appeared anywhere before.Together with the anonymous volunteer project Gnida, we discovered dozens of other websites using specific search parameters. Connecting elements included the registration data, which followed the same pattern. Random addresses and names were combined, and similarly structured Gmail addresses link three websites together, respectively. Furthermore, the websites often published the same content, which had been altered using AI for each of them.

CORRECTIV has published the list of the 102 German-language domains that we found and attribute to the “Storm-1516” campaign. The actual number of websites could be even higher.

Notably, there seems to have been no attempt to hide the technical infrastructure – unlike in the “Doppelganger” campaign. It is transparent that the websites are hosted by three providers, including the German company Sim Networks from Mannheim. When confronted by us about the propaganda sites, Sim Networks simply stated that such enquiries could only be processed and answered “on the basis of a legally binding court order or upon the instruction of the public prosecutor’s office.” The Lithuanian hosting giant Hostinger said they were investigating the information and would take appropriate action if necessary. The US company Namecheap did not respond to a request for comment.

Reporting: Alexej Hock, Max Bernhard, Sarah Thust, Till Eckert, Max Donheiser

Fact-Checking: Alice Echtermann

Editing: Alice Echtermann

Design: Laila Shahin, Ivo Mayr

Translation: Ellie Norman