How Russia enlisted German politicians, business leaders and lawyers to ensure German dependence on Russian gas.

With the flow of Russian gas through the Nord Stream pipelines now stopped, everyone in Germany and the wider world understands: without these imports, the cost of heating homes and running businesses is much greater. Every household asks: how much heating can we afford? Businesses fear for their very existence.

But the question of how Germany became so dependent on Russian gas has received less attention.

One obvious answer is that for years Russian gas from energy giant Gazprom looked cheap. But behind this superficial calculation, there were networks of German politicians, energy executives and lawyers who led Germany down the dangerous path of dependence. Some of this is already known. Now, for the first time, we aim to present a comprehensive picture of this Russian Gazprom Lobby, something which we intend to regularly update.

Clearly, Russia sought to use the gas pipelines to strengthen its influence over Germany. To this end and over many years, it systematically set up inconspicuous organizations that targeted German politicians – from both the center-left Social Democrats (SPD) and the conservative CDU/CSU bloc that formed the country’s coalition government until 2021 – to support increased gas supplies from Russia.

Russian lobbying efforts worked. At the start of 2022, more than half of Germany’s gas came from Russia. And there were advanced plans to increase this percentage even further. Notably, Germany’s approval of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline in 2018 opened a deep rift between Berlin and its Eastern European neighbors wary of Russian expansionism.

Germany made vulnerable to blackmail

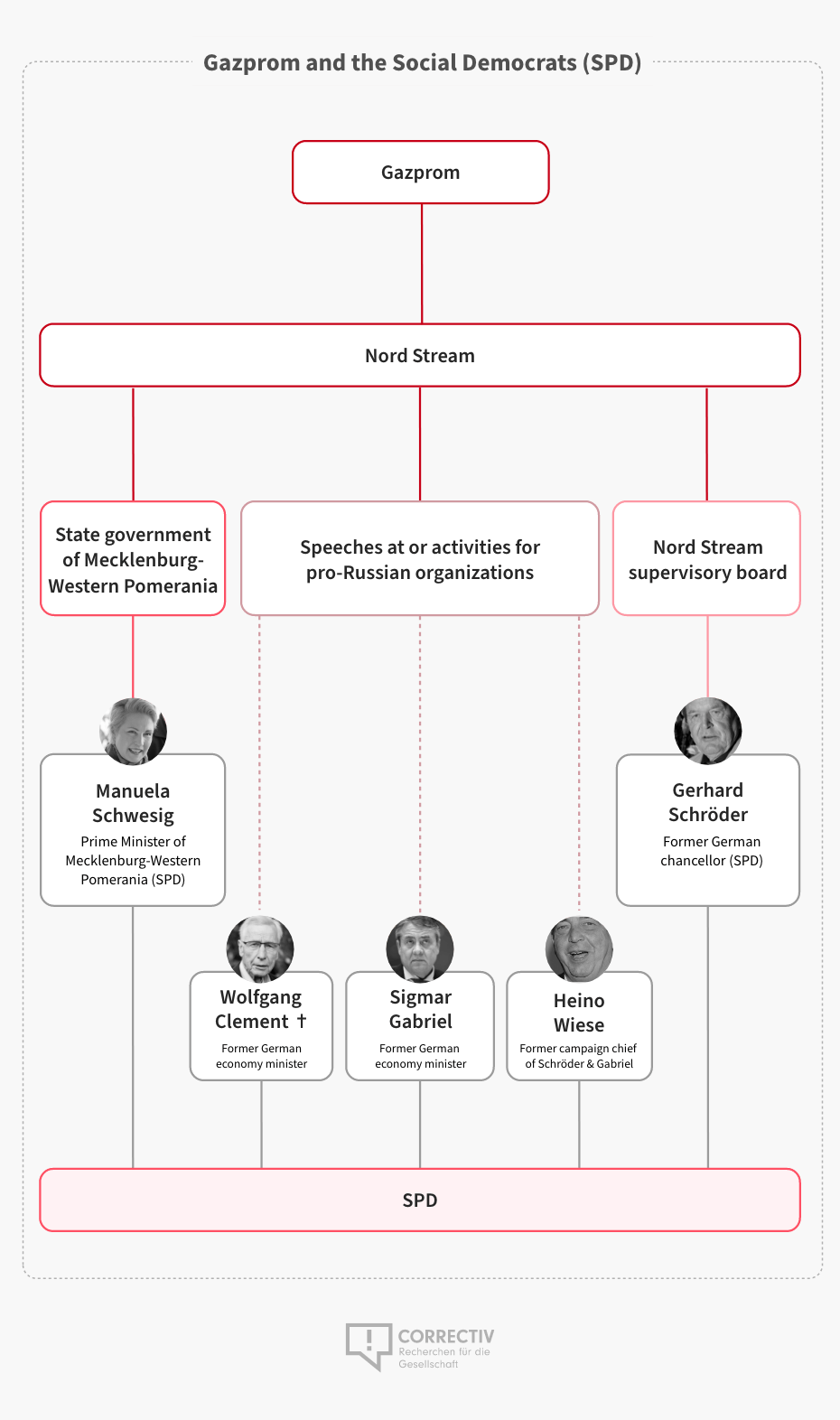

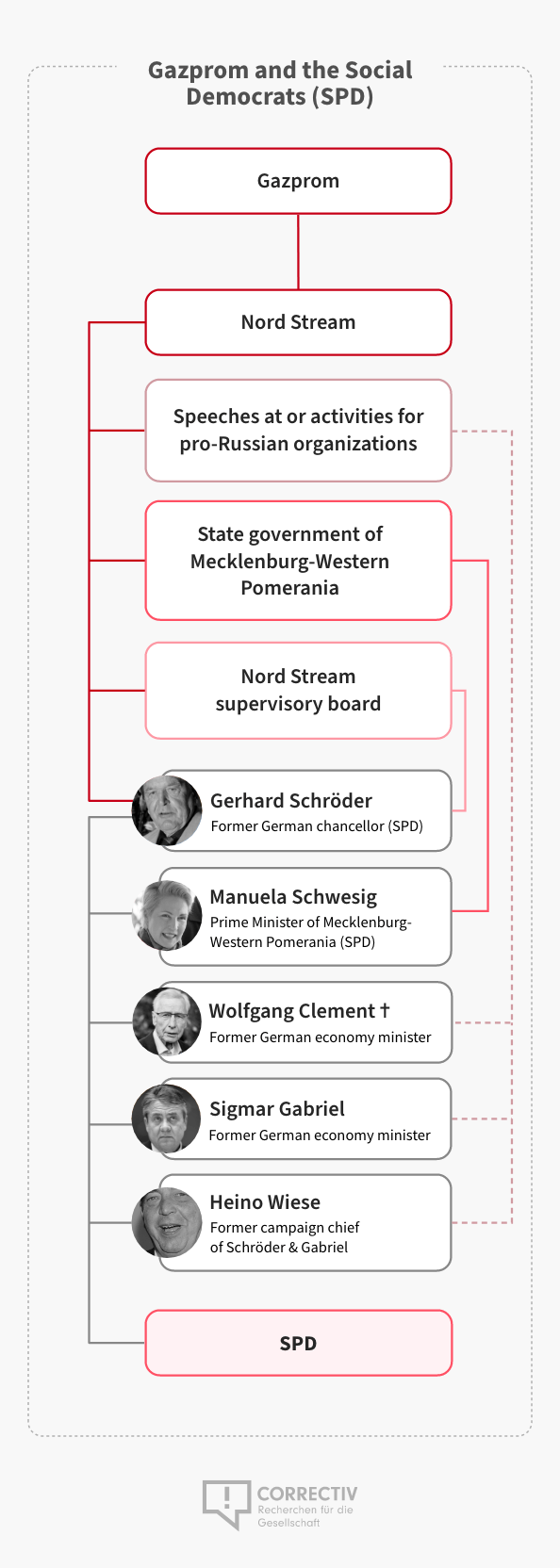

CORRECTIV research in cooperation with Policy Network Analytics (PNA), a private initiative for transparency in politics, shows for the first time how wide-ranging the lobbying network really was. It was not only Gerhard Schröder, the former Social Democrat chancellor who almost as soon as he left office in 2005 became Russia’s best-known lobbyist for Russian interests in Germany.

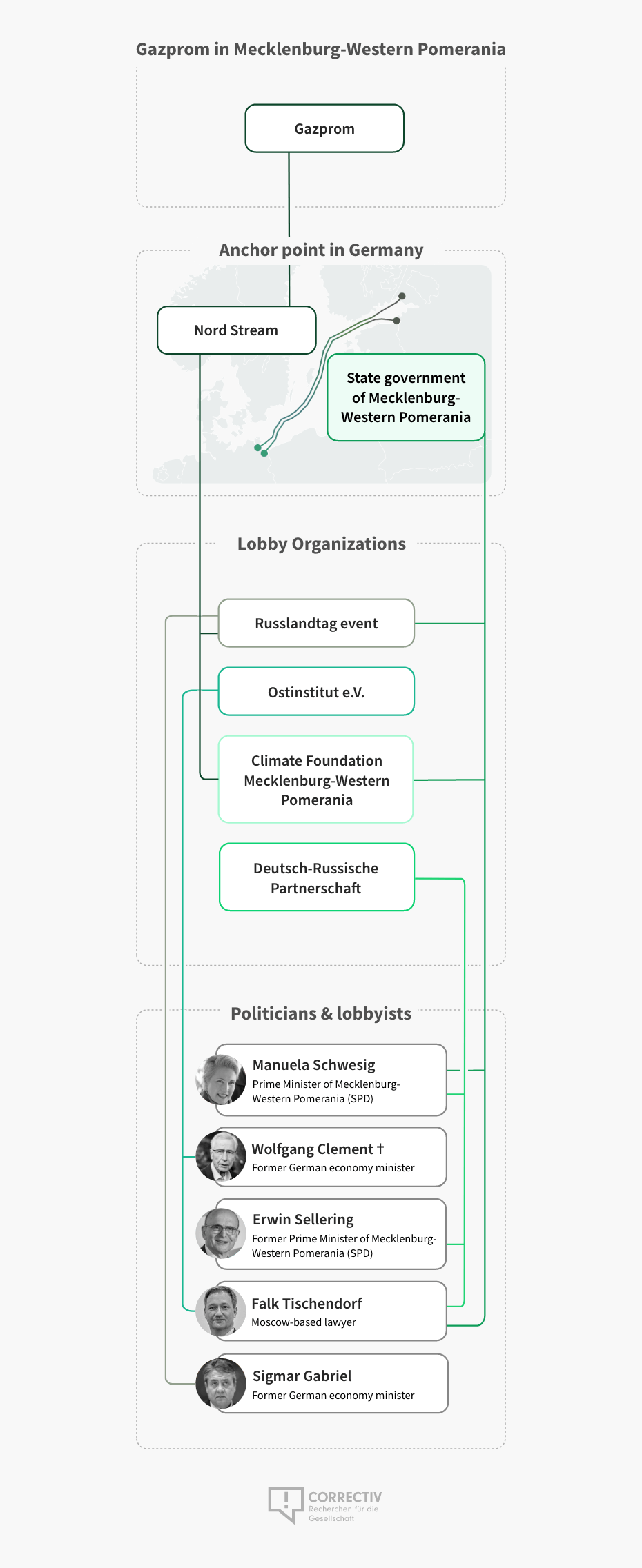

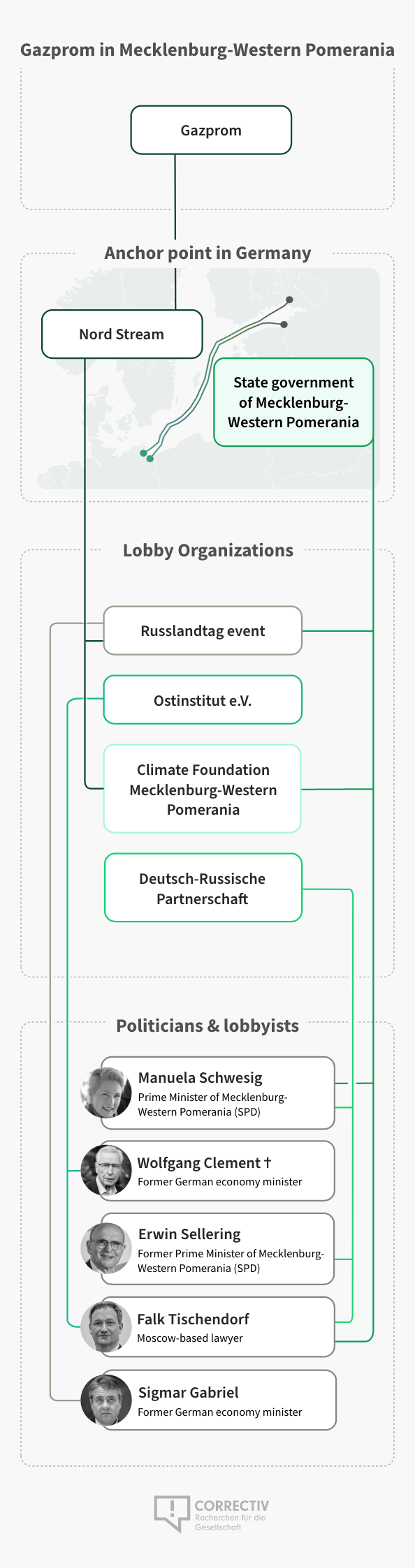

While conservative politicians were also involved, several senior SPD federal politicians joined Schröder in doing Russia’s bidding in Germany. Besides these top Social Democrats, our investigation has identified two key clusters, one in the coastal state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (MV) that borders the Baltic Sea and one in the eastern state of Saxony, both formerly in the Soviet-controlled GDR. Germany’s states play a significant role in some policy areas and both MV and Saxony were strategic to Russia as entry points for its pipelines.

In both states, politicians dependent on the SPD and CDU power structures all too eagerly attended events organized by associations that seemed to be concerned only with good German-Russian relations and which didn’t appear to represent hard-core corporate interests. These events included sponsored music festivals and discussion forums. But it was ultimately about the co-opting of top politicians, and in the case of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania even its Minister-President. The result was that Germany became vulnerable to Russian political and economic blackmail.

The individual associations, forums and events may have seemed harmless, but they followed a certain pattern that can always be traced back to the interests of Gazprom or to the Russian state itself. This lobbying is not in itself illegal in Germany. But through the permanent contacts and talks with Russian strategists, the country’s political leaders lost sight of the state actors into whose hands they had placed more than half of Germany’s gas supply.

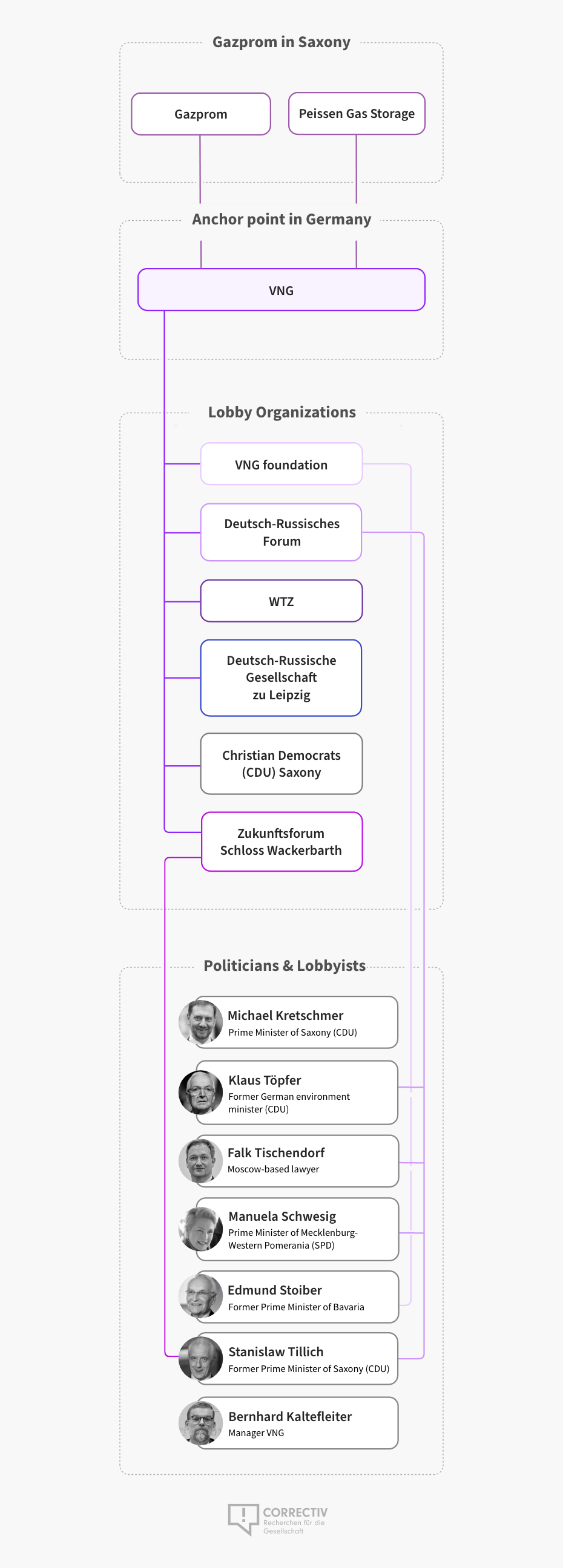

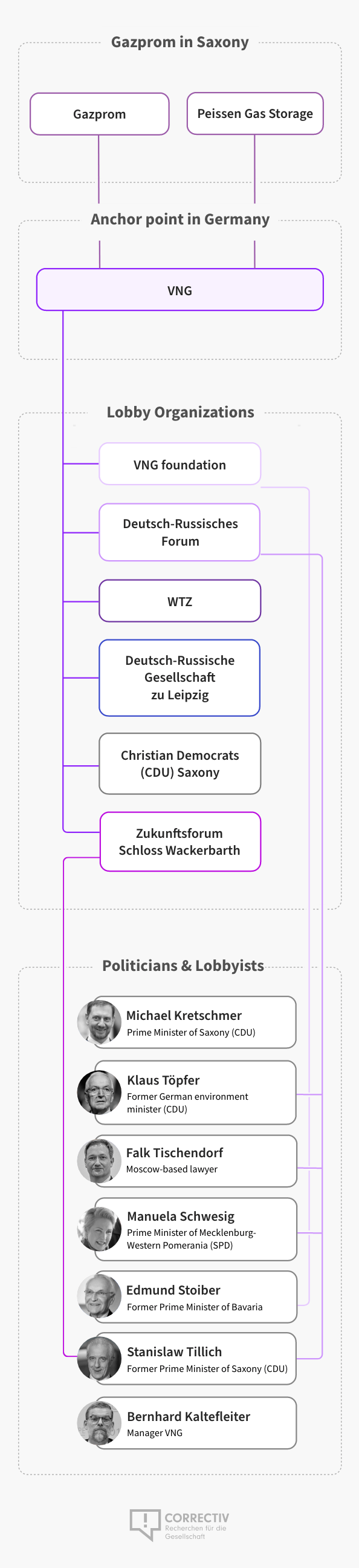

VNG: the company behind a web of seemingly harmless associations

Of the 75-strong Russian delegation which travelled from Russia to Nuremberg in April 2012 for the fifth ‘Deutsch-Russische Rohstoff-Konferenz’ (DR-RK or German-Russian Raw Materials Conference), one Moscow-based German national stand out.

Falk Tischendorf worked in the Moscow office of the commercial law firm Beiten Burkhardt (he is now a partner in the renamed Advant Beiten). The German lawyer has been advising international companies operating in Russia since the early 2000s. His name keeps cropping up both in the network of implicated politicians who attended conferences, and in the founding of various Russia-related associations. Tischendorf did not answer questions put to him by the authors of this investigation.

At the 2012 Nuremberg conference, German and Russian businessmen met politicians to discuss German-Russian cooperation in the field of natural resources. Speakers included former CSU politicians such as Klaus Töpfer and Edmund Stoiber, as well as the later Bavarian Minister-President Markus Söder.

The chairman of an association with a very similar name – the ‘Deutsch-Russische Rohstoff-Forum’ (DR-RF or German-Russian Raw Materials Forum) – wrote a welcoming speech for the ‘Deutsch-Russische Rohstoff-Konferenz’ (DR-RK or German-Russian Raw Materials Conference). In the gas lobby networks, association and event names that sound confusingly similar keep popping up.

This is certainly no coincidence and this confusion is desirable. The various associations and forums pretended to be full of committed people. In reality, the same stakeholders and politicians met again and again. The speeches were interchangeable, the message unvarying: natural resource cooperation with Russia must be strengthened.

Gas executive as busy lobbyist

The man who wrote the welcoming address to the 2012 conference was Bernd Kaltefleiter, an executive at the Leipzig-based energy company VNG (Verbundnetz Gas). Kaltefleiter is also a board member of an association whose conferences have frequently brought together current and former politicians and lobbyists.

Research shows that VNG has been linked to several pro-Russian lobbying organizations or events in recent years. (See below.)

Since Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, this activity has ceased. The association says it receives no funds from Russia and represents German and European interests in energy policy.

Matthias Platzeck, a former SPD minister president of the eastern state of Brandenburg long known for his close ties to Russia, was also involved in a separate VNG foundation.

So what kind of corporation is it whose executives involve themselves in a whole range of foundations, associations and conferences with confusingly similar-sounding names that connect Russian interests and German politics?

The VNG Group recently hit the headlines in Germany when it asked for billions of euros in state aid – the exact figure was undisclosed — in response to turmoil in the gas markets. VNG is one of the biggest gas importers in Germany with decades-old links to Russia. At the beginning of September, VNG went cap in hand to the federal government because it no longer had access to the gas it used to buy from Russia.

The energy crisis has also hit other gas importers hard. But VNG stands out for its self-inflicted dependence on Moscow. VNG has been buying its gas from Russia under long-term supply contracts since the 1970s. Many eastern German municipalities own shares in the company although the majority owner is German utility EnBW.

The connection to Russia is even more obvious on the VNG supervisory board, where Matthias Warnig was a member for more than five years. Warnig, a former officer in the GDR’s Stasi intelligence service and managing director of Nord Stream 2 among many other appointments, is a close confidant of Vladimir Putin and Gerhard Schröder. He is now on the US sanctions list.

VNG: inseparably linked to Russian interests

With sales of almost ten billion euros, the Leipzig-based group was inextricably linked to the Russian gas sector. But not only that. VNG and Gazprom jointly own the large Peissen gas storage facility in the northern German state of Schleswig-Holstein. In 2019, VNG signed new, long-term contracts with Gazprom after the old GDR supply contracts expired. VNG had many reasons to promote Russian interests in Germany.

And it did so with the help of conferences at which responsible politicians also gathered. VNG defends itself against the accusation that it was promoting Russian gas interests. The conferences were about an exchange of expertise, it says, where German and European positions on issues such as natural resources and climate change were formulated in consultation with Russian representatives.

A network for Russian gas in Saxony

One of the conferences was the Deutsch-Russische Rohstoff-Forum (DR-RF or German-Russian Raw Materials Forum) co-founded by the VNG Group. The three-day event took place annually from 2007 until the Covid pandemic, thirteen events in total. The internet still has videos of participants in St. Petersburg and Düsseldorf discussing the importance of Russo-German cooperation during the day, and later in the evenings, enjoying lavish entertainment in St. Petersburg castles or luxury hotels. What is striking – and this also goes for the entire network – is the overwhelming preponderance of men. In Düsseldorf in 2016, for example, more than 70 men spoke while fewer than 10 women were present.

The former federal minister of economics Sigmar Gabriel (SPD) and Saxony’s minister president Michael Kretschmer (CDU) were also regular participants. Then minister Gabriel spoke in 2016 in favor of ending the sanctions imposed on Russia after its 2014 occupation annexation of Crimea. As recently as 2021, CDU premier of Saxony, Kretschmer, made an appearance at the Forum.

Kretschmer has repeatedly acted as an advocate for Russian interests, also speaking out against sanctions imposed after the annexation of Crimea and more recently calling for peace negotiations with Russia. He left one question unanswered, however.

What makes a German state premier turn himself into an advocate of autocracy? One reason could be that when VNG and other Saxon companies with business in Russia did well, his state benefitted.

But his party also benefitted. VNG has sponsored CDU events, by its own account to the tune of a several thousands of euros a year. CDU party groups sometimes meet at VNG premises for their events.

Gas Talks at the CDU Foundation

But the pro-Russian lobby network did not limit itself to politicians and corporations. It also appropriated supposedly non-profit organizations. For example, the dubious roundtable of Deutsch-Russischen Zukunftsforen (DR-ZF or German-Russian Future Forums) held regularly since 2008 at Wackerbarth Castle near Dresden. Founded by the CDU-affiliated Konrad Adenauer Foundation (KAS) and sponsored by the Leipzig-based gas supplier VNG, the pro-Russian lobby network also met here regularly. One speaker at the 2012 event, for example, was VNG executive Kaltefleiter (see above), introduced in the program as VNG’s Director of Corporate Communications.

In his speech, Kaltefleiter emphasized that VNG had been “instrumental in supporting” the creation of a master’s degree program in International Energy Economics and Business Administration between the University of Leipzig and the Moscow State Institute of International Relations. The aim, he said, had been to further consolidate the dialogue between Russia and Germany and “prepare the ground for intellectual cooperation in the energy sector”.

Further events attended by the Adenauer Foundation

The Adenauer Foundation, which according to its statutes pursues “directly charitable purposes” on a Christian Democratic basis, had had close ties to Putin representatives before. In 2007, Putin’s party founded the European offshoot in Berlin of a party-owned think tank. It promptly organized a conference at which representatives of the Adenauer Foundation also spoke.

Today, Jochen Blind, spokesman for the Adenauer Foundation, says that this cooperation refers to a period “in which there were different framework conditions in the relationship with Russia compared to today.” But the Future Forums continued to take place until 2021, long after the 2014 annexation of Crimea and the sanctions imposed on Russia in its wake. The foundation explains that it wanted to “maintain threads of conversation under the most difficult conditions and clarify its own positions”, that is, until Russia invaded Ukraine again this year.

Incidentally, at Wackerbarth Castle, which bills itself as “the first European adventure winery”, Moscow-based lawyer Falk Tischendorf also gave a lecture in 2011, the man who later attended the raw materials forum in Nuremberg in 2012. Tischendorf remains an important figure in pro-Russian networks to this day, with two main regional focuses: Saxony and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (MV). Both states are important for energy supplies from the east. And Tischendorf has turned up in both.

Pro-Russian lobby activities in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania

In the MV town of Wismar, Falk Tischendorf, was one of about 20 founding members of the so-called Ostinstitut e.V., set up in 2009. Ex-SPD Economics Minister Wolfgang Clement was another. One of the aims of the institute according to its statutes is to seek exchange with neighboring countries of the Baltic Sea region on legal issues. On the list of founding members that has since disappeared from the institute’s website, there was also a high-ranking representative of the Russian Embassy in Berlin.

Russia played an important role in the substantive work of the institute which also says it received smaller amounts from Nord Stream 2 – three payments of 5,000 euros. But the institute states that it has minimal links to the extractive sector and has implemented projects in several other countries in Eastern Europe. These include the Ukrainian city of Kharkiv, from which six professors are currently guest fellows in Wismar.

Tischendorf was also active in MV in subsequent years. In 2016, the lawyer, already present in the VNG network, was appointed Russia representative for the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (MV).

MV: A pro-Russian lobbyist as Russia envoy

The Russian state thus appointed a pro-Russian German lobbyist as its official envoy. It was the culmination of many years of lobbying efforts by Russia to secure its political interests in a state where its gas pipelines make landfall. As in Saxony, former German politicians and a number of seemingly harmless associations assisted in this effort, but they were the backbone of the pro-Russian lobby networks.

The same pattern can be observed over and over. The gas lobby works its way into German politics through the back door, disguising its political interest as associations and forums. The state-controlled Russian corporation Gazprom is apparently also linked to the Russian embassy. For years, the Gazprom only appeared openly in its role as sponsor of the Bundesliga soccer team Schalke 04, based in the state of North Rhine Westphalia. Otherwise, the Russian gas lobby operated in away from the public gaze.

MV: a Russian ‘outpost’ in Germany?

Take, for example, an autumn evening in 2020 when SPD grandees and Russian gas industry representatives met in, of all places, a former coal-fired power station. At the Peenemünde power plant, on the northern edge of the island of Usedom, famous as the production site of Nazi Germany’s V2 rockets, they attended the Usedom Music Festival, one of the largest cultural events in Mecklenburg. Former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, MV state premier Manuela Schwesig and ex-Stasi spy Matthias Warnig, then head of the Nord Stream pipeline, were among the guests.

Nord Stream became involved as one of the biggest sponsors of the classical concerts on the island. But if you look at the networks behind these events, you can see the true picture. Beethoven and Mozart may have been what the general public were interested in, but in the background it’s obviously about gas.

This September, there will be classical music on the Baltic Sea island. But since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, major donors are missing. In the current list, there are only eight sponsors – all local – including nearby restaurants and a beach bookstore. In the web archive, on the other hand, it is still possible to trace how important the Russian-related sponsors once were, from the Nord Stream natural gas pipeline to the local utility Energie Vorpommern.

According to the MV state chancellery, the 2020 meeting between Schröder et al on Usedom was a “joint dinner”, not a working meeting. Manuela Schwesig was “not part of a Russian network in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania.”

But in the past, Schwesig was happy to acknowledge her good relations with Russia. In 2018, at an event at the Federal Foreign Office in Berlin hosted by the Deutsch-Russische Forum (German-Russian Forum), then SPD Foreign Minister Heiko Maas and Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov presented her with an award in front of 900 guests. It celebrated Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania’s regional partnership with the so-called Leningrad region (Oblast) around St. Petersburg.

Russian strategy: target a lower level

The German-Russian Forum is one of Russia’s many ‘subordinate’ organizations, and this military term is not misplaced. At one time, Moscow’s Deputy Minister of Industry and Trade Vasily Sergeevich Osmakov referred to the eastern state as an “outpost in Europe”. Outposts, according to Merriam Webster dictionary, are in the military sense:

a: security detachment dispatched by a main body of troops to protect it from enemy surprise

b: a military base established by treaty or agreement in another country

Russia apparently regarded Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and its state leader as such a strategic unit.

There are numerous Russian organizations with similar-sounding names in the state. For example, the so-called ‘Russland-Tag’ (Russia Day) annual festival held in Rostock which is also sponsored by Gazprom subsidiaries. Andrey Zverev, then a representative of the Russian Ministry of Economics in Berlin, explained in a 2014 interview with German daily Die Welt why his ministry was involved in the German states. The embargoes at the federal level were harmful to companies. Now you could rely on cooperation with the federal states.

The Verein Deutsch-Russische Partnerschaft (VDRP or German-Russian Partnership Association), whose chairman is Erwin Sellering, former SPD premier of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, was another such lobby creature. At various times, a representative of the Russian gas industry also sat on the VDRP board.

An address in Schwerin

The headquarters of the VDRP is at Lindenstrasse 1, in Schwerin, MV’s state capital. It is here that MV premier Manuela Schwesig’s controversial Stiftung Klima- und Umweltschutz MV (Climate and Environmental Protection Foundation MV) had its offices. The Gazprom-financed foundation was supposedly created to launch environmental projects. In reality, it appears to have been a thinly disguised mechanism to circumvent US sanctions against the Nord Stream 2 pipeline. For example, it operated the ships that finished work on the Baltic Sea pipeline when other companies exited the project.

These comrades of the SPD and envoys of Moscow: it is a small circle in Schwerin that meets again and again and, often in the guise of cultural and sporting events, promote the mega gas projects such as Nord Stream 2.

In Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, other beneficiaries of Nord Stream money include the nationally successful volleyball club SSC Schwerin and the art association Pro Kunsthalle.

Only since the Russian invasion of Ukraine has the state government tried to distance itself from Russia. The German-Russian Partnership Association will not in future receive any more funding from the state – to date it has received 250,000 euros. Manuela Schwesig’s climate foundation will be dissolved when its economic business operations have been wound up, the state chancellery states. This will probably take until the end of September.

Russian lobbying reaches far into the SPD

On the board of the German-Russian Forum which presented Manuela Schwesig with her award in 2018 there was also a man from Hanover, the capital of the German state of Lower Saxony (separate from Saxony), by the name of Heino Wiese. He is known to only a few, but he too is an important protagonist in the network. Wiese is an official of the SPD, many of whose leading lights have had great difficulty in breaking with Russia even after the full-scale Russian war of aggression against Ukraine.

The most high-profile champion of the lobby network between Russia and the SPD is undoubtedly Gerhard Schröder, German chancellor from 1999 to 2005. His friendship with Putin became clear on Christmas 2001 during a horse-drawn sleigh ride near Moscow. This was followed by an honorary doctorate from St. Petersburg University when Schröder called Putin a “flawless democrat.” Later, friend Schröder would adopt two children from a St. Petersburg orphanage and become head of the supervisory board of pipeline operator Nord Stream. Even today, he remains loyal to Putin.

But the powerful energy giants from Russia had many other advocates from the SPD. Sigmar Gabriel, who in 2015 as Germany’s economics minister was partly responsible for putting German gas storage facilities in Russian hands, is well known. Gabriel, along with Schröder and Erwin Sellering, Manuela Schwesig’s predecessor as premier of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania later publicly cast doubt on the charge that Putin was responsible for the 2020 poisoning of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny. Gabriel declined to reply to CORRECTIV’s questions concerning his lobbying work. Indeed, the former SPD minister threatened to take “legal action against [CORRECTIV]”.

Returning to Heino Wiese, who applauded Manuela Schwesig’s honor at the German-Russian Forum. Since 1990, Wiese has been managing director of the SPD district of Hanover and the Lower Saxony state association. The SPD man was closely associated with both Gerhard Schröder and later Sigmar Gabriel, acting as their election campaign manager. A member of the Bundestag (German Parliament) from 1998 to 2002, he founded the consultancy Wiese Consult in Berlin in 2006.

First comrade, then honorary Russian consul

In 2016, Wiese was appointed honorary consul for Russia in Hanover, switching sides from German state politics to the Russian. Wiese also showed himself to be generous to his own party during these years. Between 2009 and 2017, the SPD in Hanover received almost 50,000 euros from Wiese and his consulting firm, including a couple of years when he was Russia’s honorary consul.

Wiese is reported to have once said of Economics Minister Sigmar Gabriel, “I worked him on the Russia issue.” For a short time, Gabriel owned shares in a consulting firm owned by Wiese called VIB International Strategy Group. Heino Wiese did not respond to CORRECTIV’s questions.

All three men, Wiese, Gabriel and Schröder, endorsed the Nord Stream pipeline in public appearances and have repeatedly called for an end to sanctions against Russia. Meanwhile, soon after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February, Wiese announced that he had resigned from his post as honorary consul “with deep sadness.” He added, however, that he would continue to work in the German-Russian Forum and the German-Russian Chamber of Foreign Trade in Moscow to improve relations between Russia and Germany.

Gazprom's lobby strategy worked

The ‘Hanover Connection’, i.e. the alliance of men from politics and business around Gerhard Schröder, certainly paid off for Russia. Gazprom was able to push through its second Nord Stream pipeline, buy gas storage facilities in Germany and increase German dependence on Russian gas to over 50 percent.

The lobbying network also worked well in the two eastern German states of Saxony and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, which are crucial for the arrival of Russian gas into Germany.

The influence of the Russian gas industry on Germany is remarkable because it ran through so many camouflaged structures in which German politicians from both the CDU and the SPD were happy to be involved. The patterns are the same, whether it was influence in Saxony because of gas supplies or Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania because of the gas pipeline or a direct line of communication into the German federal government.

The overall connections used by Russia’s gas sector and its business partners are confusing. We have therefore sought to concentrate on the most important channels. To get an idea of the ramified networks, other connections are listed below. Not all of them are of equal importance, there are differences between supervisory board members of gas companies and speakers at a lobbying event, but all of those mentioned have allowed themselves to be sucked in.

Our investigation into the Russian gas lobbying is ongoing. We are constantly adding to our findings, not only to document who was involved but also to expose the structures of these lobby networks. In hardly any other area of public life is the effect of foreign influence on German politics so obvious. And certainly in no other area are the consequences of this influence so serious and far-reaching as they are in the case of gas from Russia.

Text and Investigation: Justus von Daniels, Annika Joeres, Frederik Richter Fact-checking: Jean Peters, Marlon Krüger Design: Friedrich Breitschuh, Belén Ríos Falcón, Benjamin Schubert Communication: Luise Lange-Letellier, Valentin Zick, Jamie Grenda, Anne Ramstorf, Maren Pfalzgraf

This investigation is a collaboration with Policy Network Analytics (PNA). PNA analyzes openly available information to pursue its mission of making transparent hidden networks of politicians. PNA investigations have been published in cooperation with Guardian, Welt, FAZ and Tagesspiegel, amongst others. You can contact PNA here.