“I’ll be heading back to the Philippines. This time though, hell is a bit hotter.“

In the Philippines, President Duterte is killing thousands. Jacque Manabat is a journalist for the biggest Filipino TV station, ABS-CBN. At the moment, she is working for correctiv.org in Berlin. How does it feel to go back to the Philippines as a journalist?

“Through her acts of public service, Sienna came in contact with the members of a local humanitarian group. When they invited them on a month-long trip to Philippines, she jumped at once.”

“I’ve run through the gates of hell.”

Dan Brown, Inferno.

Dan Brown once described my country as the gates of hell. Although I was bit taken aback, it certainly has some truth to it. In a few months, I’ll be heading back home. This time though, hell is a bit hotter.

Graveyard shift

The seven-hour difference means I often talk with colleagues working the graveyard shift. From these conversations, and the news online, it seems that the war on drugs has escalated. Our investigative team at the ABS-CBN broadcasting network tallied drug-related deaths to 2,695 – just May 10, after the presidential elections, to December 10.

I, too, was assigned the graveyard shift. The smell of blood mixed with the humid air became too familiar to me. One to two murders a night in the metropolis was average. The police call them “salvage victims.” They weren’t salvaged, but I believe they were victims: Some had their hands tied behind their backs, others with bodies taped and fit into a sack. No matter how the families of these victims cry out for help and ask for justice, they knew that their experiences were simply another story to be told.

That was over four years ago.

This year, I believe my colleagues covering the night beat have a much greater tolerance to corpses. The number of killings rose to an unprecedented level after President Rodrigo Duterte openly vowed to kill 100,000 criminals during his final campaign rally:

“Forget the laws on human rights. If I make it to the presidential palace, I will do just what I did as mayor. You drug pushers, hold-up men and do-nothings, you better go out. Because I’d kill you. I’ll dump all of you into Manila Bay, and fatten all the fish there.”

In an average night in July, around 30 people were gunned down by unidentified men or killed during a buy-bust operation. The statistics recently dwindled to around 14 a night in the metropolis. Each has a unique story to tell.

The graveyard shift journalists, telling these stories, go through rigorous stress debriefings. Some of them admit that they fear for their lives. “I believe that the killers are just around whenever we are in the location of a crime scene. I just feel it.”

Jacque Manabat.

Privat.

I cannot imagine the trauma that has become part of their daily grind – all the blood, gore, tragedy and outrage. These things eat into parts of your soul.

“Our day starts when their lives end”

This signage is posted at the door of the homicide division of the capital.

Before the police and the local government units were our primary sources for night shift stories. Now the police is giving my colleagues the cold shoulder, they told me.

In one particular instance, a citizen used his cellphone camera to film how a man pleaded for his life inside a shanty in the capital. The police ignored his pleas and killed him.

The police started to decline interviews and refused to provide information about the incidents. This makes journalists’ jobs more difficult. And makes it harder for the public to understand what is really happening.

It’s alarming how some netizens respond to the crime stories we air. Some people say that these victims deserve to die and laud the government for killing the alleged “drug addicts.”

Our country’s extrajudicial killings have caught the attention of the world.

I have repeatedly been approached by some of my colleagues in Berlin asking for clarification on what is happening in the Philippines. They read about the rise in killings and the rising skepticism towards journalists. I realized how hard it is to explain that some people feel safe with, or maybe even because of, these killings of alleged drug dealers and users. They believe killing these people will lower the crime rate.

President Duterte has been portrayed as the Filipino Adolf Hitler by critics. Duterte himself compared his war on illegal drugs to the Holocaust.

“Hitler massacred three million Jews. Now, there is three million drug addicts. I’d be happy to slaughter them. At least Germany had Hitler. The Philippines would have…“ he said, pointing to himself.

Weaponizing social media with fake news

Public discussions, especially those on social media, are becoming uglier and uglier in the Philippines.

This was felt strongly during the presidential elections campaign. Before I left the Philippines, I received private messages from faceless accounts. The individuals writing these messages accused me of being a journalist paid to hurl dirt at our newly-elected president, either on behalf of the past administration or the opposition.

Comments like “you are brainless” or “I hope you get raped” hurt, but I ignored them and continued doing my job. I aired a story on how some of the government agencies address corruption successfully and I was told: “You suck up.”

I can handle that, but what I hate the most is the circulation of fake news.

It’s so frustrating and depressing how the community perceives them to be true. No matter how often journalists dispute these fake news stories, people continue to be blind supporters. They re-post these stories until they reach over 10,000 shares on Facebook

One of the government politicians even posted a fake photo of a raped girl in a field and accused journalists of turning a blind eye to this horrible incident. Using reverse search image shows that the story originated in Brazil and not in the Philippines. But staunch supporters continue to distrust the press and follow these fake accounts.

Fake news has somewhat tarnished our authority as the fourth estate.

Some have expressed disgust over the media industry, saying that fake news stories are more credible than the rigorously researched stories we air.

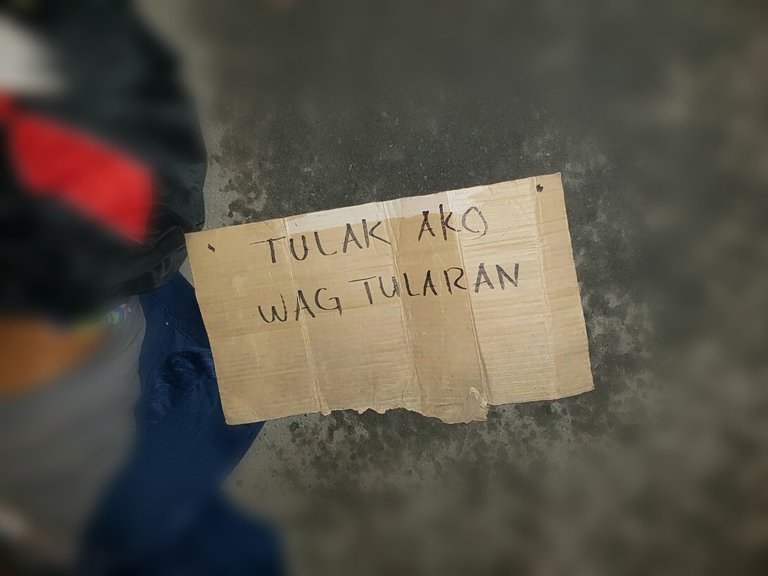

Found close to a dead body: „I’m a drug pusher. Don’t become someone like me.“

Anjo Bagaoisan, ABS-CBN Reporter

In 2016, fanatics and fake news spread like wildfire. Journalists became the targets for blind followers.

Veteran journalist Inday Espina-Varona also experienced threats from fanatics. The worst was months ago, she recalls. One person threatened that he would trace Varona down to feast on her and was told: “Let’s see where your activist courage will get you.”

Al Jazeera journalist Jamela Alindogan and international freelance journalist Gretchen Malalad have also received death threats from netizens when they aired stories on the war on drugs.

The National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP) urged colleagues to report all threats directed at journalists, so that it will be properly documented and action can be taken.

For some journalists, chronicling history with all these setbacks may cause fear. But these threats and fake news stories motivate me even more to change the nation – one story at a time.

The second most dangerous country in the world

All of these social media threats become more alarming once you look into the recent history of the Philippines.

The Philippines is listed as the second most dangerous country for journalists, with 146 killings in the past 25 years, according to the International Federation of Journalists.

More than forty years ago, when our nation was placed under former President Marcos’ dictatorship, the press were among the first to be silenced. Outspoken activists were also kidnapped, tortured and killed. The company where I work, ABS-CBN, was shut down.

Seven years ago, 58 people were gruesomely murdered in the southern part of the Philippines. Thirty-two of them were journalists.

The press was in convoy to the provincial capital to cover the filing of candidacy for the town’s governorship when the convoy was attacked. When people arrived at the scene, they saw bullet-ridden bodies sprawled around the vehicles. Others were thrown into a mass grave. The government allegedly used a digger to bury some of the bodies.

Found close to a murderer, a small piece of paper and a picture. Probably the directions leading to one of the victims.

Anjo Bagaoisan, ABS-CBN Reporter

Until today, the victims have been denied justice.

Now with President Duterte leading the country, he has continued inciting hate towards journalists.

In one of his early press conferences, Duterte said: “Just because you’re a journalist, you are not exempt from assassination if you’re a son of a bitch.”

He added that many of the slain journalists accepted bribes or were corrupt, and they may have “done something wrong.”

Sometimes the President’s speeches can be confusing. He says something, but means something else. The next day, a team of spokesperson clarified his statements. After that the public blamed the press for “misinformation” and “misunderstanding.”

NUJP said in a statement: “As journalists, it is our duty to report events as faithfully as we can. To blame us for the consequences of what those we cover utter or do is tantamount to asking us to abrogate our duties and be silent. This we cannot and will never do.”

Should I be neutral as a journalist?

Being part of the mainstream media is a lot of pressure. People expect you to be neutral; others despise you if you are open about your opinions.

But I believe that journalists must speak out amid conditions of outrage. We have to be fair, not blind. Journalists should never pick any fights with citizens on the web. It makes no sense to be petty and mean like the „trolls“ are. If need be, we should block them.

As I head back to the Philippines, I plan to stay vocal online and continue pursuing my passion of airing stories.

This is my only way to be of service to Filipinos – as my company slogan puts it.

I’m still free and safe

With the rise of the trolls, the perception of the press changed.

Some of my friends, who are not working in journalism, tell me: “It must be hard to be a journalist nowadays with all the threats. Why did you become one?”

It is tempting to stay here in Europe and escape what is happening back home. The label „first world country“ implies that they are two steps ahead of us, but we are so far behind. Sometimes I don’t feel the freedom of speech, because I am afraid of being threatened, online and offline.

But when I listen to journalists who survived the reign of our former dictator Ferdinand Marcos, their stories motivate me to go back home and be the journalist that I am.

Journalist Inday Espina-Varona’s explanation hit me the hardest: “From time to time, Filipino journalists have faced great risks and actual threats. I was a young journalist in the last years of Martial Law. I know how it feels to be scared – and how to carry on. I feel free, but only because I will myself to be free. I know very well the time might come when this freedom will be threatened from all sides. I will fight the way we did during the time of dictatorship, even if it means going underground. The important thing is never to fall silent.”

This is the reality I have to face when I get back. I am coming home, Philippines.

Jacque Manabatis a senior journalist in the biggest broadcasting network in the Philippines, ABS-CBN News. She has been in the media industry for more ten years. At the moment, Jacque is a fellow of the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung in the Berlin office of correctiv.org. The writer’s views do not reflect those of ABS-CBN Corporation or of its News Division. You can find Jacque on Twitter. The pictures have been shot by Anjo Bagaoisan, a reporter at ABS-CBN. You can find more of his pictures and stories on his blog.