10 Years After The Massacre Of Andijan

Even ten years after the massacre in Andijan, Uzbekistan, the European Union does not work for a clearance of this crime. At first the EU imposed sanctions to force Uzbekistan to name the people responsible for the bloodbath. In the provincial city of Andijan, several hundred peope were shot by security forces. In the contrary, the non-profit investigative newsroom CORRECT!V found that EU diplomates after the massacre only needed a year to undermine the sanctions against Uzbekistan.

The armored cars show up in the afternoon. They leave their positions and roll along the main road, carrying soldiers with their submachine guns cocked. They roll onto the square filled with people. There are thousands: men, women and children. An armored vehicle pushes a car out of the way, and then, without warning, the soldiers start firing into the crowd.

I can’t believe my eyes. I don’t want to accept it. I knew that Andijan was surrounded by soldiers and I figured they would move into the city, but I always said: they will not shoot at unarmed people. They will occupy the square at night when it’s empty, but they won’t shoot.

Von den Panzern schießen die Soldaten in die Menge, auch auf unseren Reporter Marcus Bensmann. Vincent Burmeister

And now they are shooting. A cold shiver runs through my whole body. I stand there frozen, in the middle of people running, shouting, falling. I finally react after a burst of gunfire hits the pavement beside me. I jump into an open ditch, lie above a foul puddle and hear the muffled bangs of the Kalashnikovs, without rhythm, ongoing, whipping through the air, hard, loud. Crying men, begging: „don’t shoot!“ The whimpers of the wounded, the screams of people dying.

After several minutes the gunfire stops. Where is my wife? We came here together this morning, her name is Galima Bucharbajewa. Like me, she is a journalist, at the time she was already one of the most widely known critical voices in Uzbekistan. I jump out of the canal and see her lying in the same ditch, a few meters away. She is pale. A camera is hanging around her neck. A man runs to her and shouts. „Take some pictures!“ Galima starts to shoot photos.

An armored car drives up. We grab each other’s hands, run back to the ditch and jump inside. Shots ring out above us. Both of us are on the phone. Galima gives an interview to CNN. The shooting stops again. We climb back up. Dead bodies are lying all around. Men carry wounded people away. A man with a gun walks towards the armored cars’ position. His step is calm. We start running.

The peaceful protest

Two days earlier, on 11th May 2005, I am already in Andijan to report on a trial. Twenty-three local businessmen are charged with absurd allegations. An enormous crowd has gathered in front of the courthouse: men, women, children and elderly people. Most of them wear festive dress; the men in suits, shirts and ties, the women with long dresses and headscarves. So many people, but silence hangs in the air. No honking cars, no shouts and no cursing, as is usually common in Central Asia. The silence is irritating.

This is a silent protest against Uzbek president Islam Karimov, against his police, his intelligence services, against widespread arbitrary power. And this is a challenge. Karimov has not permitted demonstrations in years. For three months, these men and women have kept gathering in front of the courthouse to demand that the 23 businessmen be released.

Drei Monate lang versammeln sich die Menschen still zum Protest. Am 13. Mai wird die Stille von Gewehrsalven durchschlagen.

Vincent Burmeister

Then as now, arbitrary arrests are a daily occurrence in Uzbekistan. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the former Soviet official Islam Karimov took power in the most populous Central Asian country and set up a police state. The 77 year old president not only oppresses the political opposition, he also sees any independent production of wealth as a threat. Independent journalism is prohibited, and Uzbeks require official permission to speak to foreign reporters. State forces will use any measure to silence their critics. At a traffic control, police smuggled drugs into the journalist Salijon Abdurachmanov’s car, since then he has been in jail.

Many members of the secular and educated middle class have left the country. They live in Russia, the USA, Europe or Israel. They have left behind a poor and subjugated population. Corruption is a part of life from the cradle to the grave – according to Transparency International, Uzbekistan is among the ten most corrupt countries in the world.

In 2002, two photos were released to the public. Craig Murray, who was the British ambassador at the time, leaked them to the media. The photos show the bodies of two dead men. Their skin is bloated, taut and unnaturally red – torturers had boiled the men in prison. The UN Special Rapporteur on torture, Theo von Boven, investigated the case. He found that torture is „systematically“ applied in Uzbekistan.

But in the West we read and hear little about this. Uzbekistan is important. It is strategically placed, bordering on Afghanistan. Since the beginning of the „War on Terror“ in 2001, it has been a NATO partner. The US Air Force and German military use air bases in Uzbekistan to supply their troops in Afghanistan.

The demonstrators in Andijan belong to a religious group around the spiritual leader Akram Juldaschjev. Drawing on the Qur’an, he proclaimed a number or rules for life and business. He calls on his followers to live by the principles of fairness, justice and diligence – which has landed him in jail for over 20 years. He is accused of being an Islamist. That has been a common pretense to silence critics in Uzbekistan, especially since 2001. Many of his followers are successful and respected citizens. They own furniture, textile and brick factories, mills, bakeries and restaurants. They combine religious virtue with business acumen; they are the middle class of Andijan. They work with the authorities, have schools and hospitals renovated. Uzbek television praises them, they even receive state awards for their efforts.

But at some point they must have become a disturbance. In the summer of 2004, 23 of the most successful men in the community were arrested. The accusation, once again: they were Islamic extremists. Their property was seized, they were interrogated and tortured.

On the day of the trial I speak to the public prosecutor. He had demanded long prison sentences for the businessmen. I ask him why they were so dangerous. He says they had „not committed any crime yet“, but they should be convicted to prevent future crimes, „as a warning“. Meanwhile, rumors spread among the demonstrators. The verdict was about to come. The defendants were likely to be discharged. I fly back to the capital.

Usbekistan. Die Strecke von Andischan nach Taschkent wird von Sicherheitskräften kontrolliert.

Paul Blickle / ZEIT ONLINE

The uprising

Two days later, on May 13th in the early morning, I receive a phone call. The situation in Andijan has escalated, armed men have stormed the prison and freed the 23 businessmen. My wife and I quickly pack up and leave. The Uzbek military has blocked the overland route, but we manage to get to Andijan within a few hours in a postal plane, on foot and by taxi.

Now everything has changed. Demonstrators guard the streets, they have established posts. The men are beaming. They walk upright, chins raised, and seem proud. This is new. The secret police’s constant hounding of anything different particularly affects young men. At any time they can be arrested. But on May 13th 2005, the men of Andijan are no longer afraid.

Thousands of people are in the central Barbur square on a space of just about 200 by 200 meters. Speeches echo through speakers, children run around. The theatre, a relic of Soviet classicism, is on fire – but nobody is putting it out. The rebels have turned the city building by the square into their headquarters. A steel fence surrounds the glass building. Uzbek government files lie around on the street. Documents fly through the air.

A few men are standing around the entrance to the building. They carry arms. These men are from the city, not foreign fighters or Afghan Mujaheddin. I meet Sharif Shakirov, one of the leaders who I already met during my first visit. He wears a tidy white shirt. His two brothers stand beside him. A few hours ago they were still in jail. They still wear their prison-issue trousers. Their faces are livid. They seem exhausted. Sharif Shakirov takes us into the building, leading us to an open office, and tells us about last night:

The demonstrators were told that the 23 prisoners would be released on May 12th. But the regime did the opposite. That evening, the Uzbek secret police begin arresting men. The police seize cars that are parked near the courthouse. Every protest movement has people that are prone to violence. In Andijan, peaceful protesters hold them back for a long time. Until the arrests. Then people lose their patience: a few dozen men move on a barracks. The soldiers flee. The men storm the building and arm themselves. Then they move to the secret police building and demand the release of the prisoners. The secret police fires into the crowd. Around 30 people die there, says Shakirov.

The men move on to the prison. They use a truck to ram open the gate. The guards flee. The cells stand open. The prisoners are free. That same night the rebels occupy the city building, taking police, members of the secret police and the public prosecutor as hostages. Shakirov says the hostages are on the second floor of the building.

Overnight, peaceful protesters have turned into insurgents. It was unplanned and spontaneous, they seem overstrained. Their leader is called Kabuljon Parpiev, a wiry man with short hair. He is negotiating with the Uzbek Interior Minister Sokir Almatov. They don’t want a revolution, he says, only justice – and the release of their religious leader Akram Juldaschjev. The Interior Minister threatens to have the square stormed if they do not surrender immediately; soldiers would fire on the people, even if it left hundreds dead.

A few armed men stand in front of the city building. In the garden, old men prepare Molotov cocktails. A man in a dark suit poses with a rifle. The barrel is pointed at me. I shout at him to take that thing away. He tells me to calm down, it’s not loaded. Today, the photo of this man serves the authorities as proof that dangerous terrorists were in the city.

Outside, on the stage, people pass around the microphone. Everyone can get in line and say something. For the first time, people in Uzbekistan are free to say what they want. The people complain about arbitrary treatment, they demand justice. Nobody speaks of establishing an Islamic state.

This goes on for the whole afternoon.

Then the armored cars show up.

Die Menschen versuchen vor den Kugeln der Sicherheitskräfte zu flüchten. Wir hören das Schreien der Sterbenden durch den Kugelhagel hindurch.

Vincent Burmeister

The politicians

Several hundred people are killed in the Andijan massacre, but nobody knows exactly how many. After that the security apparatus slams down its iron fist: hundreds are arrested after the massacre. People who manage to flee are kidnapped in neighboring countries. Marked by torture, they confirm the Uzbek state’s version of events in show trials: Islamist terrorists and foreign fighters instigated the uprising with the help of Western media. And Uzbek security forces did not fire at people.

Politicians around the world react – appropriately, it initially seems. The Council of EU Foreign Ministers demands that the Uzbek government allow for an international and independent investigation. The Uzbek government refuses. As a result, the European Union imposes sanctions in October of 2005: a weapons embargo and a travel ban for top Uzbek officials. A cooperation agreement is also put on ice.

The Uzbek government reacts in turn by banning NATO planes from Uzbek airspace. The dictator Karimov threatens to close Western military bases in Central Asia. The German government now has a problem: it needs the base by the Uzbek airport Termes to supply troops in Afghanistan. But it can hardly just make amends with a dictator who has unarmed demonstrators mowed down.

But then the German chancellor Schröder is voted out of office, and Angela Merkel’s grand coalition takes over. A „policy of rapprochement“ towards Uzbekistan is put in motion. In October 2005 – before the new government has been formed – Interior Minister Sokir Almatov is treated in a special clinic in Hannover – the same man who threatened to shoot demonstrators in Andijan, and who sits at the top of the EU sanctions list. Nevertheless, the Foreign Ministry gives him a visa.

In December 2005, half a year after the massacre, Friedbert Pflüger, state secretary in the German Defense Ministry, travels to Tashkent to speak to the dictator Karimov. Pflüger promises a „fair“ consideration of the Uzbek point of view in the evaluation of the „events“ in Andijan. Karimov returns in the favor: the German military can stay in Termes.

Around a year later, on November 1st 2006, the German Foreign Minister Steinmeier meets the dictator. „Sanctions are not an end in themselves“, says Steinmeier after this meeting. The demand for an independent investigation into the massacre is subsequently dropped – in favor of „expert talks“. These talks, confirms a high ranking EU diplomat today who wishes to remain anonymous, were an „exit strategy“ from the sanctions. Nobody had an interest in imposing „everlasting sanctions“ against the Central Asian country, the diplomat says.

The results of these talks, which took place between December 2006 and April 2007 in Uzbekistan, are still kept secret to this day. The Uzbek regime promised a „human rights dialogue“ and „reforms“; they abolished the death penalty and implemented justice reforms. But these reforms are only on paper. People continue to be tortured in Uzbek prisons.

But EU diplomats raise no objections. They began with big words, now they hardly make a sound. The „events of Andijan“ should not strain relations between Uzbekistan and the European Union anymore.

Während des Massakers verstecken sich meine Frau Galima und ich in einem Wassergraven. Mit viel Glück überleben wir das Blutbad.

Vincent Burmeister

Survival

My wife and I are incredibly lucky. Just in time we run away, then more armored cars begin to encircle the Barbur square. Soldiers move ahead, shooting at anything that moves. We escape into an alleyway, run through a district, stop to catch our breath at a bus stop. A car stops and we get in. Back at the hotel, pale and soaked with sweat, I call my mother. Suddenly I can’t contain myself, I begin to sob, can hardly get out any words.

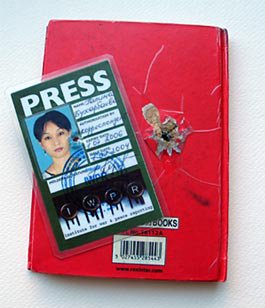

I look into Galima’s big eyes. She is also in shock. But we can’t allow for these emotions, not right now. I set up the satellite telephone. We call news desks around the world to report on the massacre. At one point, Galima takes her notebook out of her backpack – and sees that it was pierced by a bullet. Now we see that the bag also has two holes, an entry and an exit hole. Thanks to a wonder, Galima is unharmed. We work late into the night.

Die Kugel einer Kalashnikov durchschlägt Galimas Rucksack, ihr Notizbuch und ihren Presseausweis.

Vincent Burmeister

That day I realize that our lives will never be the same. Galima needs to leave the country immediately. After witnessing the massacre, Uzbekistan is no longer a home for her. We wanted to get married that summer and had moved into an apartment together. For the first time in my life I had bought a nice sofa. I told my friends that I was finally settling down. I had been traveling around Central Asia since 1994. I was fascinated by the region between the Caspian Sea and the Chinese border. After the Soviet Union collapsed, five new countries gained independence in Central Asia. The last blank spot on the map. I wanted to be an explorer. I worked as a reporter for the Swiss and German media. The region gained increased attention from the press after the attacks in 2001. Suddenly the whole world was looking to Central Asia.

CPJ

Galima and I had been together for a year. We had known each other for a while before that. She ran an English-language media organization, the „Institute for War and Peace Reporting“. I saw her for the first time in Berlin in 2002. Speaking at a podium discussion, she attacked the Uzbek regime and argued with a representative. I sat in the audience and was enthralled. She was so beautiful and fragile – and yet she seemed so brave. Later we did a number of stories together. In 2004 we did a report on the families of suicide bombers. Every day we drove out to see their relatives.

After that we were a couple.

We wanted to get married in August, in Bukhara, in an old merchant building. My family and friends were going to travel there from Germany. Some were afraid. I always told them to calm down: nothing would happen. It’s not dangerous to travel to Uzbekistan. That is no longer true. „We won’t be able to celebrate here“, I told my wife in the hotel after we fled from the square, not in this country anymore.

Trying to return

A terrible storm sets in. It pours down from the sky. Lightning and thunder. The entire night we hear gunfire. And the sound of armored cars driving past our hotel into the city center. A greasy meal from the hotel kitchen. Then we have a fretful and short night’s sleep.

The next morning we want to return to the square. The people are all excited. A woman shouts: you’re journalists, you have to tell us what happened! But we don’t get far. There are checkpoints everywhere, we are stopped by security forces. They search us. They find rolls of film and take them away. And they see Galima’s notebook. „Today is a second birthday“, whispers a plainclothes policeman. Then they put us in a car. They have to take us out of the city, they say, they can’t guarantee for our safety. A warning. They put us in another car. At the edge of the city we find journalists who are not allowed to enter. Again I work the whole day, write, telephone, give interviews.

Galima could be arrested at any moment, she needs to leave as soon as possible. But how? The overland route is too dangerous, the soldiers have set up checkpoints everywhere. At the airport they would arrest her. I call a friendly diplomat, she sends a car. The next morning a white Jeep picks up Galima. We plan to meet later in Azerbaijan.

Diplomaten eines Nicht-EU-Staates helfen meiner Frau Galima, aus Usbekistan zu fliehen. Wir werden nie wieder zurückkehren können.

Vincent Burmeister

Taking a few detours, I manage to get back into Andijan. A „stringer“, a local contact, helps me find victims. He gets me copies of death certificates. We walk through the city and visit the casualties’ homes. One man was shot in front of his own house. He almost made it. But then a bullet hit him right by the entrance. The blood still glistens on the street. The door frame is riddled with bullet holes. The troops chased their victims through the streets.

Then the stringer is arrested. His parents call to let me know. I make my way to the jail. Before that I call up all the foreign representations I know and tell them to call me every ten minutes on my cell phone. I find the commanding officer and act tough. I tell him that my stringer has done nothing and that the whole world stands behind me. Whenever I get a call, I tell him: that was the German ambassador. That was the US embassy. Those were the Swiss.

He gives me back the man. Another officer whispers to him: we’ll get you anyway, when the journalist is gone we’ll arrest you again. I take him with me to Tashkent, to the capital, later he is smuggled out of the country in a banana box.

My visa is running out. I know I will never come back to Uzbekistan. I take a plane to Baku and meet Galima.

Since then we have lived in six countries and 14 apartments. In the whole world we told people about the massacre. In Brussels and in Washington and in London. We were convinced that Germany, Europe and the USA could not just accept this. The Uzbek state called us information terrorists.

But our hope was naïve. Andijan and the massacre were forgotten.

Steal our Story

Help yourself! CORRECTIV is a non-proift. We want the maximum audience for our investigations. That’s why we’d like you to reuse and spread our stories.

You can use everything that you can download in this box for your blog, your online publication, your newspaper or radio for free.

There’s only one condition: please send us an email to info@correctiv.org. If you have questions, email us as well. Thank you!

Get our story as an easy to copy text

You can also use the following material: