Constant threat

Israel has endured several heavy outbreaks of resistant germs. The nation’s response has been exemplary. Despite the peculiarities, other countries are following its model.

In Israel, politics permeate through ever facet of the country including the health care system. The authoritarian structures, built for defense against external and internal enemies, have shown benefits in infection control.

In 2006, a resistant germ was ravaging the country’s hospitals. A bacterium, of the Klebsiella pneumoniae variety, was introduced from New York. Almost no drug can fight the germ, not even carbapenem, an emergency antibiotic. It seemed like the bug’s spread was unstoppable. At its peak in March 2007, 185 hospital patients were infected. The bug sickened more than 1000 people; half of them died. In hospitals, the bug has a mortality rate of up to 50%.

It took months until the outbreak was contained. And even now, the bug has not disappeared completely. It’s lurking, waiting for the next attack.

What has Israel learned from the epidemic? What can others learn from Israel?

The Hadassah hospital in Jerusalem

At first everyone was fighting the outbreak on their own, says Mitchell Schwaber, an infectiologist at the Sourasky Medical Center in Tel-Aviv. There wasn’t a network connecting the different hospitals. It was only at an informal meeting of the country’s infectiologists when they realized that everyone was facing the same problem. They set out to establish a task force, the National Center for Infection Control. Mitchell Schwaber became its director.

The task-force got to work: Patients were to be screened for the bug, and infected people were to be isolated and treated by dedicated staff. What was special about the task force was that its recommendations were binding. „We got legal authority“, Schwaber says. His team could demand information and enforce directives.

Those same directives are still in place today. Schwaber’s team is still collecting data daily on resistant germs from every hospital – unimaginable for big, decentralized countries, such as those in Europe or the US.

Despite the benefits that come with collecting this data, Schwaber’s directives are controversial. For example, there are questions surrounding if and when patients carrying a resistant germ should be isolated. Some argue that the measure is laborious and can stigmatize the infected patients and their nurses. Schwaber is convinced that the orders are justified at least when it comes to this particular germ. His team’s protocol has since been adapted internationally.

Mitchell Schwaber, Leiter des National Center for Infection Control in seinem Büro

Secret weapon

State authority is not the only tool Schwaber uses to fight infection. He has a special weapon. Her name is Ester Solter; she is a nurse. The jovial woman comes into play, when hospitals are not following Schwaber’s directions.

In 2012, during another frightening Klebsiella outbreak, a hospital in eastern Jerusalem contacted Schwaber because newborns were getting sick and dying of a mysterious infection.

Eastern Jerusalem is the Arabic part of the city and its exact governing status controversial. The tight control that Schwaber has over other hospitals was of no use here. However, he still asked for the data. When he got it, he was worried.

“My God, something had been going there“, the doctor says. At the peak of the outbreak every third child in the hospital had the bug. Schwaber sent nurse Solter to help the doctors on site immediately. The biggest problem turned out to be the language barrier.

Solter did educational work: How are samples taken correctly? How is the laboratory equipment used?

It is unfortunate that it took an outbreak at a neonatal station for this exchange to happen.

At the end, however, Schwaber’s team was successful. His recommendation? „Have a system in place before an emergency comes. Don’t let yourself be surprised.“

Schwaber knows that his nation is special: It is small and has a strict, centralized bureaucracy. In a country that lives in permanent state of emergency, reactions are swift and effective.

On the other hand, its hospitals are always full. „We are over 100 percent capacity all the time“, Schwaber says. The nation’s population is growing. In the last decade, it assimilated more than a million immigrants, most of them from the former Soviet Union. This makes population growth higher than ten percent. And yet, the hospitals capacities have remained the same, Schwaber complained.

Bug tourism

Additonally, Syrians and patients from abroad, with infected wounds or who are taken up for humanitarian reasons, such as survivors from the Bucharest discotheque fire of 2015, are being treated in Israel. They often bring resistant bacteria with them and upon arrival have to be isolated, Schwaber says. Because of Israel’s high standards of medical care, the country is a destination for the global medical tourism industry. But when humans travel, so do the germs.

Schwaber is always on alert. Every day he is prepared for a new outbreak. MRSA, Acinetobacter or a gut germ? It could be anything. His worst nightmare? Not having enough money, doctors and hospitals beds when an epidemic breaks out, he says. Because in reality he is not only fighting resistant germs, but also against limited resources and politics. Every year seems more difficult. „We live in tough part of the world. Money that goes into defense is missing somewhere else.“

The Nobel Prize winner

About halfway between Tel-Aviv and Jerusalem lies the renowned Weizmann Institute. More than 2500 people do research there. The institute has produced three Nobel Prize winners in chemistry.

Ada Yonath is one of them. The 76-year-old sits in a black T-Shirt in a tiny seminar room and explains why she antibiotic resistance is an enormous threat to global health.

Nobel Prize winner Ada Yonath researches novel antibiotics

She wants to use her insights of the molecular structure of bacteria, for which she was awarded the Nobel Prize, to develop novel antibiotics that target parts of the bacterium with exceptional precision. She introduced her ideas to pharmaceutical companies – being a Nobel laureate gets you invited everywhere, she says. She told the companies that people were going to die young unless new antibiotics were developed. Nobody ever got back to her.

Now Yonath researches the concept on her own. It would not be the first time that she ends up surprising the scientific community.

The hidden infectiologist

Allon Moses is a leading infection control specialist in Israel. He is not easy to access. His office in deep in the catacombs of the Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem and nobody is around to help show the way.

Despite also being one of the world’s most renowned infectiologists — he played an important role in contains the 2006 epidemic — nobody seems to know him. This is typical. Infectiologists work in the background, without much attention.

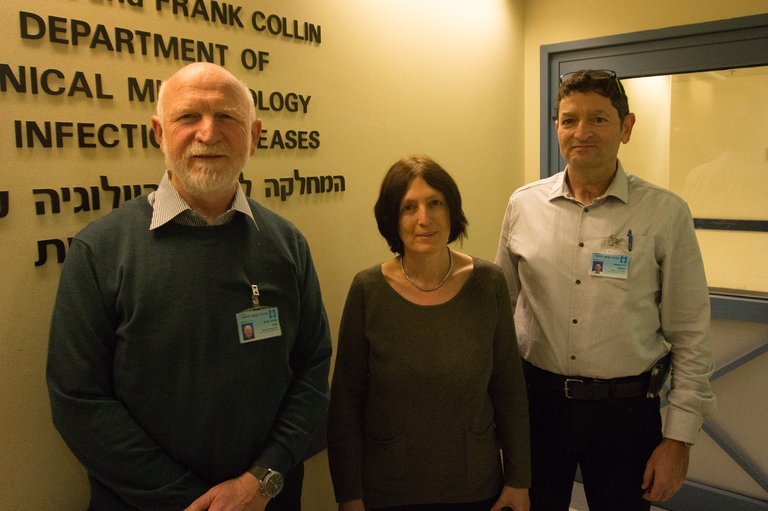

Eventually a young doctor leads the way up and down stairwells, through corridors, and finally to Moses’ modest office. Inside is a desk with a computer and on the shelves are microbiology journals and textbooks. Moses’ team is also in attendance. Carmella Schwarz, head nurse, and Shmuel Benenson, infectiologist, sit on office chairs.

Moses is a friendly man with a white beard and receding hairline. He sits behind the computer screen on which he shows presentations and data on infections. He is proud of this system because it shows every infection reported at the whole hospital.

What has he learned from the outbreak? That good infection control is difficult, he says. That there is not one solution; many small steps make the difference.

One of the main tasks of Moses’ team is to convince the doctors to report infections and nurses to thoroughly wash their hands. They even make sure that cleaning personnel scrub more thoroughly.

Allon Moses, on the left, and his team: Carmella Schwarz and Shmuel Benenson

Any prospective hire for Moses’ team needs to be an infection control expert with charm and diplomatic skills. Being able to participate on a team is essential. „Infection control is no job for a single person“, Moses says. Everyone needs to be included, from the clinic boss down to the cleaners.

Since 2006, a lot has gotten better, Moses says. It is easier to get the doctors’ attention; they are more interested in hearing his advice. Still, psychological intuition is necessary in his team’s daily work. Moses remains alert. The constant threat, he says, is an inherent part of living in Israel.