The Hidden Fleet

At sea, humans are just one commodity among many. The smugglers of the Mediterranean load up their cargo ships with drugs, weapons – and refugees. We went in search of their ships and their shell corporations. The trail took us from the Middle East to Piraeus and Hamburg.

Around midnight, they reach their destination: a secluded bay near the port of Mersin in eastern Turkey. The lights of the city are off in the distance. In the water, there are three old little motorboats. In these boats, they’re supposed to be carried out to sea, out to the large cargo ship Ezadeen. The ship is waiting in international waters. You can’t see it. The only thing that penetrates the darkness is the cold wind.

Amr’s cell phone suddenly rings. It’s his eldest son.

“Where are you?” asks Amr, a Syrian businessman and father of four children.

“At our apartment.”

Amr starts to get angry.

“This is no time for jokes!”

But it’s no joke.

They had been separated on their way to the dock. The smugglers bundled Amr, his wife Rania and two of their children into a minibus. Their oldest children, both in their early twenties, had to go in a different minibus. The drive past the vacation resorts on the Turkish coast took three hours. The convoy got separated. Amr and Rania arrived at the harbor undisturbed. The other minibus, they now learned on the phone, hit a roadblock. The police sent it back.

What now? What are they supposed to do? Should they decide not to ride out to the Ezadeen that would take them to Europe, and wait for their two children?

They’ve been stuck in Turkey for over a year. They’re from the Syrian coast. Amr is well-off. He owned a business there that sold construction equipment. They fled their country when a massacre was perpetrated one and a half kilometers from their home.

His wife Rania tries to reason with the smuggler. She’s educated and speaks several languages. But it’s no use. The smugglers tell them they have to leave. This is their chance. Tonight. They’re told to wait for their children on the Ezadeen. The ship would be at anchor for another few days. They finally allowed themselves to be persuaded, and head out into the darkness. The Turkish port city of Mersin is left behind.

It’s the day before Christmas Eve. The year 2014 is almost over.

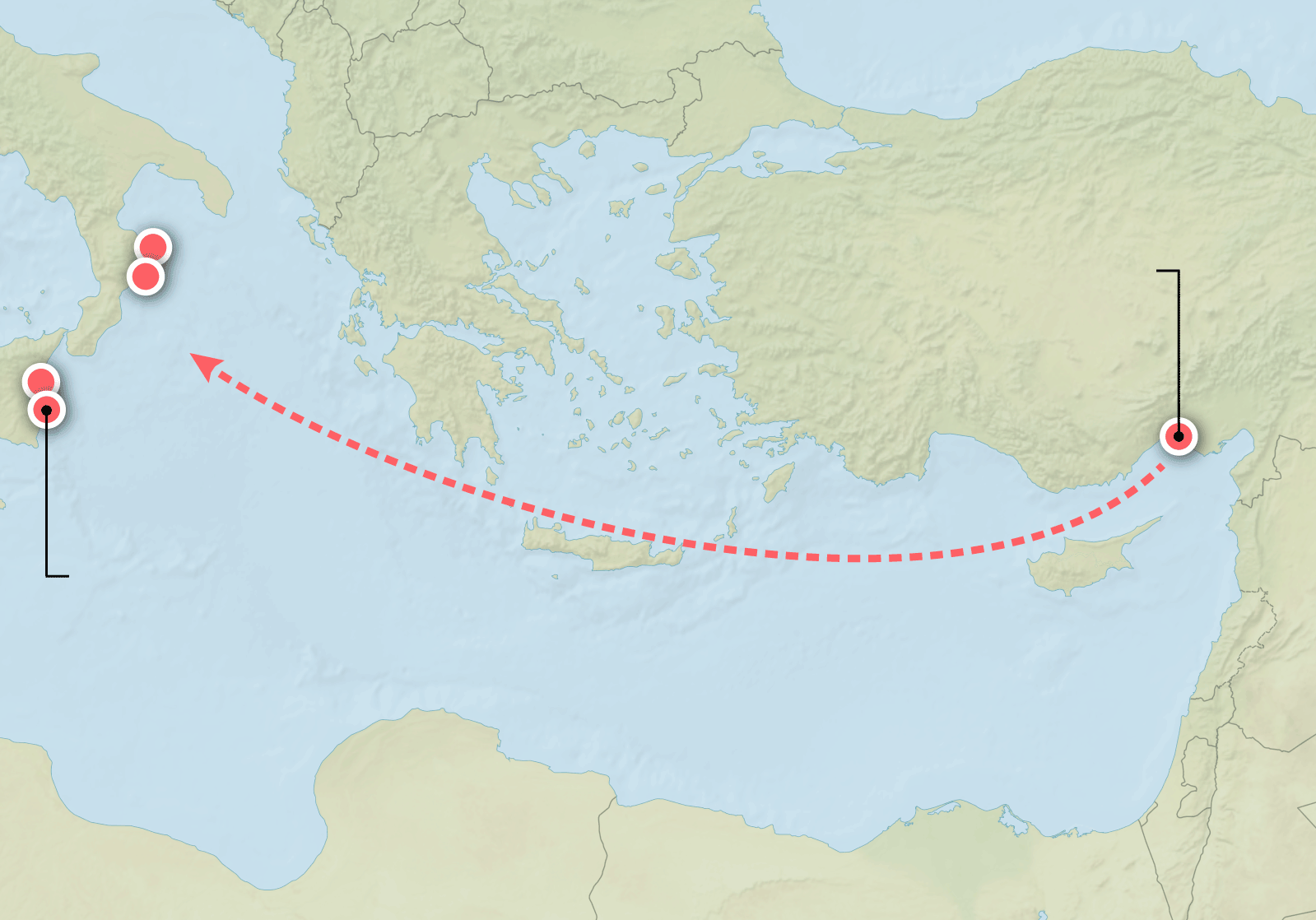

Italy

Turkey

Mersin

The smugglers were running the logistics involved in the use of cargo ships for migrant smuggling out of this Turkish port city.

Augusta

Augusta one of several Italian ports where the cargo ships filled with refugees arrived.

Smugglers have been on the Mediterranean since time immemorial. A few years ago, however, the routes changed, as did the rules of the game. Libya collapsed. In Syria, combatants needed to be supplied with weapons. Even the drug smugglers sought new routes. And hundreds of thousands of people had only one thought: to flee the war for the safety of Europe.

Beginning last summer, large refugee ships suddenly started to appear along Europe’s coasts.

In 2014, three days before Christmas, the Merkur 1 was seized by the Italian coast guard off the coast of Sicily with about 600 refugees.

In 2014, on New Year’s Eve, the Blue Sky M was moored in the port of Gallipoli at the heel of Italy’s boot with about 800 refugees.

In 2015, on January 2 at around 11 p.m., the Italian coast guard brought the cargo ship Ezadeen into the port of Corigliano Calabro in southern Italy. The ship was carrying 350 refugees.

The Merkur 1, the Blue Sky M, the Ezadeen: These aren’t inflatable boats that anyone can operate. They’re vessels that are part of the fleets of large shipping companies. They’re cargo ships between 60 and 100 meters long that carry everything under the sun between Gibraltar, the Black Sea, and the Indian Ocean. Timber, livestock, grain. And refugees.

Bookkeepers are needed for keeping the ships’ records in order. Longshoremen for loading and unloading. Mechanics for running the engines. Captains for navigating over the sea. This takes an organization.

The investigative newsroom CORRECTIV wanted to find out just who was behind the refugee ships. At least 14 of these cargo ships have been en route in the Mediterranean. Who procures and loads these ships? Who buys cargo ships for a final voyage to carry refugees only to then toss the ships away like a disposable lighter? What organizations, what networks, and what people stand behind it? Is there a connection between arms smugglers, drug dealers, and those who transport refugees?

Amr and Rania get settled on board the Ezadeen. Their two children, who are 16 and 19 years old, explore the ship and run across its decks. Boredom soon sets in, however. Their cell phones have no reception on the ship. They can only guess what’s happening on shore. The captain of the Ezadeen, who’s also Syrian, tells the passengers that they’re not allowed on deck. No one should see what cargo he had loaded.

On the second night more refugees come on board. Rania and Amr feverishly await their children’s arrival. But they don’t appear. On the third night there’s no boat at all. What they don’t realize is that high-level politics has intervened. The EU made clear to the Turkish government that it didn’t want any more refugees ships to put out to sea along the Turkish coasts. The authorities sealed off the ports. Nobody is going to leave.

Amr had booked a cabin for his family near the bridge. Here the wait is at least bearable. But below the deck of the old cattle freighter, people lie on carpets right in the middle of the enclosure where sheep and cattle once stood, trying to protect themselves from they icy cold of the metal decks. Pale fluorescent tubes cast a feeble light.

Refugees are using blankets to shelter from the cold inside the Blue Sky M, a freighter that carried around 800 refugees.

AFP Photo / HO / Courtesy of Syrian migrants

The trail to the backers of this business leads through a myriad of records. Radio signals emitted from transponders aboard the vessels indicate where they are located to the exact second. The data is public. Shipping companies know where their ships are. So do the insurance companies and the customs offices. For several months, we intercepted and stored this data for ships that sailed along the Syrian coast.

We could see where the cargo ships were moored and where they seemed to move directionless about the sea. We were able to follow the vessels through the Suez Canal to the ports of Sudan and up along the shores of Iran – where, probably because they switched off their transponders, they suddenly disappeared. Later, we found them again off the coast of Libya, Morocco, or Spain.

For example the cargo ship Ahmad Prince. From Novorossiysk, the Russian Black Sea port known as a transit point for weapons, it sailed for the Syrian port of Tartus, a stronghold of the Assad regime. This is where the Russian Navy has its most important base in the Mediterranean. A few kilometers away lies the tiny island of Arwad. Some of Syria’s main shipping families still come from here. This region remains one of the linchpins of Assad’s power.

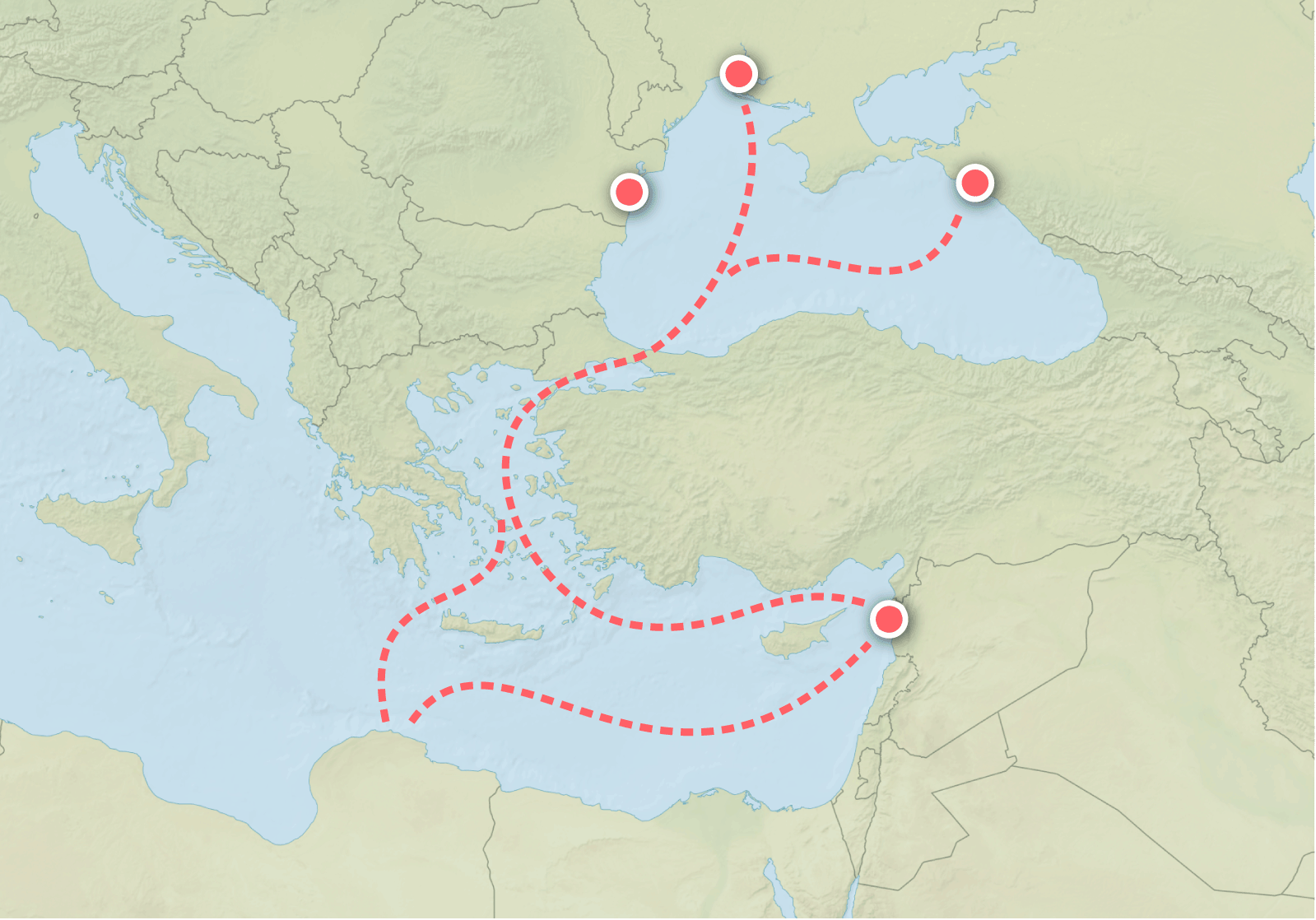

Oktyabrsk, Ukraine and Novorossiysk, Russia

The cargo ships are loading weapons in these Black Sea ports.

Constanta, Romania

This Romanian Black Sea port is an important logistics hub for the Syrian smugglers.

Tartus, Syria

Supplies and weapons are entering Syria through this port. Some members of the smuggling network are from this area.

Libya

The country’s militia are both sellers and buyers of arms and ammunition.

Experts speak of the “Odessa network” when referring to the smuggling of weapons in the Black and Mediterranean Seas: a loose association of shipping companies from Russia, Ukraine and Syria. They carry weapons and ammunition from the Black Sea to Syria and onto the militias in Libya and Somalia. On the way back, they transport ammunition from Sudanese factories to Syria. Since the outbreak of the Syrian civil war, its been a rewarding, though barely monitored, market.

The Ezadeen’s passengers have pooled their money together. Each family contributes another 100 USD to pay for the crew, in addition to the 5,000 and 8,000 euros they had already given to the smuggler. The day after Christmas, the Ezadeen sets sail. The metal enclosures on the cattle deck begin to shake as the captain finally starts the engines.

On this first night at sea, they can already sense the wind getting stronger. The waves relentlessly push the cargo ship from one upsurge to another. Below deck, the stench of vomit intensifies. Amr goes to the bridge. The storm rattles the superstructure of the boat so loudly that it’s nearly impossible to hear yourself speak. “The next twelve hours will be rough!”, the captain calls out to him.

All day long Amr looks out from the porthole and wonders whether the old cattle freighter will be able to withstand the storm. His only consolation: The smugglers who organized the cargo ship had brought some of their own family members with them on board.

In 2013, narcotics officers from Italy and Spain joined forces. Rather than having to chase Moroccan hashish on land, they hoped they could already intercept it at sea. They called their operation “Mar de Fondo”. Soon, they also notice a remarkable change: Until 2013, most hashish had come to Europe aboard small crafts like agile inflatable rafts and inconspicuous fishing vessels. Then, on April 18, 2013, Italian authorities confiscated 20 tons of hashish in one fell swoop on the cargo ship Adam, seized near the island of Pantelleria, south of Sicily.

Italian drug squads are boarding the freighter Meryem in June 2015. They found 12 tonnes hashish on board the ship.

Guardia di Finanza, Italien

The special units of the operation „Mar de Fondo“ detained a total of 16 large cargo ships within two years. On board: a total of 250 tons of hashish.

Colonel Pino Colone’s coordinates the international missions of the Italian DEA from his imposing cherry-wood desk. He’s a numbers man in an elegant gray suit. For decades, he traced the money launderers of organized crime. Now he heads the Italian operations of “Mar de Fondo.”

The drug routes have changed since Libya fell apart, says Colone. “The smugglers have turned Libya into a warehouse for hashish.” Colone estimates that about 1,000 tons of hashish are stored in Libya. At a wholesale price of 700 euros per kilo that corresponds to about 700 million euros in all.

“The smuggler networks have transformed the Mediterranean into a highway for all kinds of illegal goods,” said Colone. “They carry drugs, weapons, and refugees. But it could also be toxic waste or anything else for that matter.”

The cargo ship Adam – where the investigators made their first major hashish find – is again in the spotlight one and a half years later. Now, the name Zain is painted on the rusty hull. On December 10, 2014, it was towed by the Italian Coast Guard into the Sicilian Port of Augusta. On board: almost 400 refugees.

Of the 16 ships seized in the drug operation “Mar de Fondo“, around half are linked to companies that are involved in smuggling arms and refugees. Italian investigators say that the smugglers have purchased some of the vessels in northern Europe and that, in some cases, they have been overhauled in the port of Hamburg for use in smuggling operations off the coast of North Africa.

Four ships, one shipping company: In July 2014, the cargo ship Zakmar is seized near Lampedusa. On board: seven tons of hashish.

In mid-November, the Captain Samin is towed into a port in Sicily. On board: almost 600 refugees.

In September 2015, the Haddad 1 is stopped by the coast guard off the coast of Crete. On board: 5000 rifles.

Altogether, these four vessels, including the aforementioned Prince Ahmad navigating the Odessa route, have one thing in common: according to shipping databases, they were operated by the same shipping company, registered in the Marshall Islands. In the local certificate of registration, a front man is registered as the owner. A ship database provides at least an address in Piraeus.

We pay a visit to the address. The area is run down. Open dumpsters and wildly parked cars block the sidewalks. In the foyer of the house sits an elderly man behind an empty desk. He has short, gray hair. His shrunken shoulders make his large nose look even larger. He’s a man who smells trouble. We ask about the shipping company we’re looking for. “There’s no company by that name here,” he says.

We dig deeper and through the analysis of phone numbers used to register websites and shipping documents presented to Italian port authorities we’re able to link the Marshal Islands-based company with its address in Piraeus to a network of Syrian business men, some of whom come from the coastal city of Tartous.

The storm plaguing the Ezadeen subsided after three days. The power went out below deck, however. The refugees have to make do with the meager light of their cell phone screens. How long would the batteries hold out? Even water is being strictly rationed.

The Ezadeen reaches the heel of Italian boot on January 3, 2015. The crew destroys the engine and signals SOS. The Italian coast guard, however, does not send lifeboats, but a helicopter. The captain shouts at the refugees: “All on deck!” The coast guard needs to see that there are numerous children and pregnant women among the refugees.

The helicopter leaves behind three mechanics. But they can’t manage to get the engines up and running again. It is not until the next afternoon, on January 4, 2015, that two large ships of the coast guard haul the Ezadeen into the port of Corigliano Calabro. The quay is teeming with aid workers and camera crews. One of Amr and Rania’s daughters collapses. She can only sob.

The smugglers register their shipping companies as shell corporations in known tax havens in Panama, the Marshall Islands, or in the US state of Delaware. Here, they’re easily able to list a straw man as the owner.

In our investigation, CORRECTIV has discovered dozens of these companies in tax havens around the world. Many ship owners set up a different shell corporation for each cargo ship. The vessels constantly change hands, from one company to another. Public prosecutors typically target the crews of the detained cargo ships, not the people behind the smuggling. That’s because prosecutors are limited to their national jurisdictions. By the time their requests for assistance to investigators in other countries are responded to, the smugglers have already established new companies. Investigators say that some countries like Lebanon do not respond to their requests for help at all.

In addition to the well-known tax havens, Greece also plays a key role in keeping the shipping industry’s dirty secrets. The country protects its wealthy ship owners. It does not require its shipping companies to be listed in the general commercial register. Anyone who requests information from the registry at the shipping ministry is turned down.

Amr, Rania and their two children managed to travel north through Italy to Germany, where today they live in a small town in the South.

They spent the first few months in a refugee camp. Just two days ago they were able to move into a house where they have at least have a room to themselves. The only place for their cooking ingredients is the window sills. Rania has prepared a plate of lentils, which we eat together at an otherwise bare table.

Amr peers incessantly at his cell phone. He can’t put it down. He’s waiting for a sign of life from his eldest son. Only his daughter, who at first also had to stay behind in Turkey, was able to make it to Germany in the meantime.

But who owned the Ezadeen, the livestock carrier that brought them to safety, alongside more than 300 other refugees? Amr and Rania said that some of the smugglers’ family members were on board. We asked them whether they know who the owner is.

Amr nods and begins to speak of the island of Arwad, the flat piece of rock near the Syrian port of Tartus. But Rania interrupts her husband: “No names, please.” She sweeps a brown strand of hair from her face. “They helped us. I don’t want to get them in trouble.”

Here is the other side of human smuggling. On the one hand, it’s organized by corrupt networks that are also willing to transport drugs and weapons. They take advantage of the plight of the refugees and demand exorbitant sums of money for the crossing. On the other hand, they also allow the refugees safe passage – not in a wobbly, overloaded inflatable boat, but in a cargo ship that can withstand storms. The family is grateful to them, and shields them. We know the answer just the same.

Investigating the shipping world is tricky. Each vessel involves at least three parties: the owner, the operator, as well as other service providers including for the compliance with safety regulations. Reconstructing exactly which one of these is responsible for a smuggling voyage is difficult. This is particularly true for Syria. International insurance companies no longer cover trips to Syrian ports. Sanctions have been imposed on the country. Syrian shippers say that this is already why they’re trying to obscure the ownership of their ships. As soon as there’s a connection to Syria, they say, their business partners get cold feet. It’s also child’s play for them to have their ships moved from one meaningless shell company to another.

In addition to satellite data, our research has also relied on the shipping database Equasis. Many ships in the end are owned by private individuals, who, nonetheless, list companies as the owners in the ship’s required documentation. Thus, information in shipping databases may diverge from the records that are found on board the detained ships. CORRECTIV has analyzed the data and routes of more than one hundred ships and companies in order to detect the contours of the network – even if it is not always clear what ship belonged to whom or at what point in time.

A number of traces point to Tartus, the stronghold of the Assad regime.

When the Ezadeen was loaded in Mersin with refugees, the numbered 5,000-dollar tickets to Europe were sold in an apartment next to a police station. One of those who organized the human smuggling operation was the Syrian Ramez Bahlawan. According to one eyewitness, he handed out and later stamped the tickets. Still, helping Syrians to exit Turkey is not necessarily a criminal offense there. Bahlawan is from the Syrian island of Arwad, not far from the port of Tartus.

In November 2013, off the coast of Rhodes, the Greek coast guard stopped the cargo ship Nour M, presumably en route to Syria from Ukraine, with 30 million rounds of ammunition on board. The list of previous owners and operators of the Nour M in shipping databases reads like a „Who’s Who“ of Syrian smugglers. One example: Mohammed Khafaji, who was busted off the coast of Lebanon in 2012 with a cargo ship that had been loaded with a full arsenal of weapons, guns, rockets, explosives, and mines.

For the Nour M, CORRECTIV also obtained cargo records and other documents. In an inspection report from the Rhodes harbor master, a Majed Markabi is named as one of the ship’s owners. The Markabis are one of the ship-owning families from the Syrian coast.

The network of Syrian smugglers that CORRECTIV has uncovered consists of around five shipping families. Their connections and companies extend over the entire eastern Mediterranean between Turkey, Lebanon, Egypt and Libya and up to the region of the Black Sea. Indeed, some of the families originate in the Romanian Black Sea port of Constanta. The Syrian civil war has also had the effect of scattering them in all directions. They now reside, inter alia, in Dubai, Sweden and also travel to Germany.

Not all their business is illegal. They also ship everyday items such as cement, wheat, and machinery. But they dominate precisely those logistical channels that the smugglers use themselves. They also use dummy corporations registered on the Pacific atoll of the Marshall Islands. This is how the smugglers protect themselves against legal prosecution.

CORRECTIV has not found any evidence of a direct link between the smugglers and the Assad regime. At the same time, their presence in the port of Tartus suggests a certain proximity. Some of them have declared their support for the regime on Facebook. Autocrats in the Arab world often maintain their relations with companies without making any direct investments. They expect loyalty and financial contributions in return for allowing an entrepreneur to operate a particular business. Besides this, the business of smuggling – the smuggling of arms into the region and the transportation of refugees out of the country – also benefits the regime in Damascus.

Majed Markabi refused to comment when reached by CORRECTIV over the phone. The others denied any involvement in smuggling. Mohammed Khafaji says that he didn’t know about the cargo of weapons on his ship. Ramez Bahlawan said that he was not involved in refugee smuggling in Turkey. He denies knowing Markabi, although they’re connected to each other through social networks.

The EU border agency Frontex claims that there won’t be any more refugee ships in the immediate future. Turkey, they explain, had neglected to monitor its coastline for a number of months. Now things are different. It’s all under control.

Actually, nothing is under control on the Mediterranean Sea, due to the lack of transparency in the shipping industry, which relies heavily on off-shore companies. The smugglers’ shell corporations are beyond the reach of Frontex. They have no reason to fear prosecution. The demand for their cargo ships is enormous. A thousand tons of hashish waits on the beaches of Libya to make the crossing to Europe. The ship owners deliver munitions for the bloody civil war in Syria and transport the refugees out of Lebanon and Turkey. Some of the smugglers have actually abandoned their bases in Turkey – though now they operate from Egypt.

Indeed, Egypt or neighboring Libya could be where the next cargo ship filled with refugees sets sail this coming winter.

This investigation was funded by the association investigate! e.V.

Contributor: Marta Orosz.

The African journalists association ANCIR helped to research local business registries. The organization Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ) helped with inquiries in Syria. The journalists Yannis Souliotis from the Greek newspaper Kathimerini and Rene Alfaro from the Honduran TV show Ojo Critico contributed to our research.

Editor: Ariel Hauptmeier

This publication is a cooperation with German media “RTL-Nachtjournal” and “Tagesspiegel”. Versions of this article also appeared in the Italian newspaper Il Fatto Quotidiano as well as the Greek newspaper Kathimerini.

Update, 26 August 2019: We have removed the names of a Greek maritime business as well as a Syrian business man from this story.