Putin’s early years

CORRECT!V has reconstructed Putin's early years in an elaborate investigation. As a young KGB officer, Vladimir Putin displays the ruthlessness that later catapults him into the Russian presidency. Putin plans the blackmail of a professor with pornographic material, he employs a notorious neo-Nazi as one of his informants – and forgives colleagues for anything as long as they are loyal.

In August 1985, Putin arrives in the East German backwoods. His official position is consular officer. But his real job, as a major in the Russian intelligence service, is to recruit spies in the GDR. This is not a place he really wants to be. Spies dream of serving at stations in enemy territory, of obtaining important information. Being stationed in an allied nation, and then in Dresden, far away from the capital – not very exciting. But at the age of 32, Putin is still at the beginning of his career: he has spent ten years in the KGB and this is his first real foreign assignment.

His closest colleague in the first two years is Vladimir Usoltsev. During this time they know everything about each other. The two men share an office and even a desk in the attic of the KGB building in Angelikastraße 4. The office is sometimes too hot or too cold.

Putin spends most of his working hours there; he writes reports and sends them to KGB headquarters. He also looks for people who would be willing to become agents and spy for him in non-socialist countries; people who would risk years in jail if they are caught.

Putin focusses on people with a special affinity for the Soviet Union, academics, business people and tourists, even right-wing extremists and criminals. According to a former agent, the pay was very modest – he only once received 30 East German Marks as a meal allowance.

At his command, Putin has an investigation team from the notorious K1 division of the East German police. The team is officially responsible for investigating political crime in the GDR, but some units within K1 secretly work for the KGB, including the troop in Dresden that is assigned to Putin. This is confirmed by two of Putin’s former colleagues in conversations with CORRECTIV and in Stasi files that we reviewed. For example in a letter, Putin asked the district Stasi office in Dresden to help restore telephone service for one of his agents whose phone service was cut off after he left the police force.

Everything the policemen write goes straight into Putin’s briefcase. The team at police headquarters is not allowed to keep an archive and does not retain copies of the documents given to Putin, says one of Putin’s agents.

Putin’s right hand man is Georg S. He is a daredevil and a roughneck; strong, ruthless and loyal. Putin’s kind of guy. We will hear more about Georg S.

A transgression

Working in the GDR might seem a little boring for an agent like Putin – but then again, it is also very easy. People like him have access to the infrastructure of an entire state. There is no „nyet“ for a KGB officer in the GDR. It is also helpful that many citizens of the GDR have direct contact with people in the West. The GDR is a honey pot for information and contacts. And Putin makes use of this. Among other things, he recruits a number of Stasi agents for the KGB.

One of them is Klaus Zuchold. When they meet, Zuchold is under training by the Stasi as a foreign spy handler.

Mr. Zuchold is a key witness for this story. CORRECTIV reporters conducted numerous interviews with the former Stasi officer over a long period of time. Zuchold is one of the few witnesses who is willing to speak openly about his cooperation with Putin. He was in regular contact with the KGB officer during Putin’s entire tenure in Dresden. As is to be expected with double agents, one can question the veracity of Zuchold’s statements. CORRECTIV is aware of this weakness, but after factchecking Mr. Zuchold’s statements in documents and in interviews with other witnesses, we found his statements to be convincing. CORRECTIV believes it is important to extensively document Mr. Zuchold’s unique testimony here.

Zuchold is a person who can easily be persuaded. According to Zuchold’s Stasi file, he was under investigation on suspicion of working for the West German spy service BND. That is a terrible allegation against a spy that could lead to a prison sentence – or to a bullet in the head.

But not with Zuchold. He is only transferred to a different unit, and later Putin personally pushes through Zuchold’s recruitment in Moscow. This is what Zuchold himself tells us. Even though the people in Moscow must be aware of the Stasi file which accuses him of being a double agent.

A possible explanation: the accusation is only a pretext for the Stasi to secretly investigate KGB agents – including Putin’s network.

The recruitment begins at a Dresden police party. A man he has never seen sits down next to him and raises his glass with the words „Prost Aufklärung“ (cheers espionage).

Zuchold is shocked. The term espionage is secret, only meant for internal use. No uninitiated person can know that Zuchold works for the Stasi in foreign espionage, definitely not someone in the police force. And if somebody does know, they are not allowed to say it, especially not over a beer. That’s the rule.

The officer who voices this code word is Georg S. from the political police K1; he works for Putin. With the word, Georg S. also blows his own cover, showing that he too is a spy. Another no go among secret agents. And so begins Putin’s recruitment of Zuchold – with a transgression.

Zuchold already knows who Putin is. In an interview with CORRECTIV, Zuchold says he first met Putin in the Jägerpark in September 1985 at a Stasi phys-ed soccer game, early in the morning at 7 a.m. For Zuchold the exercise is mandantory, while Putin is there for the fun. Putin immediately stands out due to his speed and technical skill. He scores goals for his team. Because Putin hardly spoke German at the time, they speak in Russian.

After the agents’ toast, Georg S. shifts Zuchold from the Stasi to the KGB. The Stasi is not happy about the recruitment. Putin and his colleagues keep rummaging around in the staff and resources of the GDR spy service. Stasi officials soon figure out that Zuchold works for the KGB, so they put him out to pasture. They move him from the section for foreign intelligence to the less prestigious section for observation. He no longer receives any important information.

Privately, the two men get along well. Zuchold invites Putin to his weekend house outside of Dresden. The house is near a Soviet army barracks. Zuchold jokingly calls the soldiers „my harvesters“ – because they steal apples from his garden. This joke is right up Putin’s line. From then on Putin asks Zuchold every time he sees him: how are your harvesters doing? He looks down on the Soviet soldiers. He despises them. They failed in Afghanistan. They brought shame to his country. If there is one thing that Putin can’t stand, then it is weakness, says a friend of Putin’s.

CORRECTIV has asked the Russian presidential office to comment on the information about Putin’s time in Dresden. We did not receive a response. Should we receive comment at a later date, we will update this story.

By any means

Blowing Zuchold’s cover at a party through a toast – that is no joke. But this behavior is typical for Georg S. He is notorious for not following rules. He does what he wants. He thinks he stands above everything else, says Zuchold. Again and again, he would ignore regulations and talk openly. In the Stasi he would have been fired for being careless and endangering others. But this reckless daredevil is Putin’s most important agent.

Georg S. is dominant and charismatic; he has close-cropped hair, sees himself as top dog and is a passionate hunter who rents his own hunting grounds. He proudly told Zuchold that his father was also a KGB agent who died under mysterious circumstances.

Georg S. is also known for his escapades with women. He is said to have had affairs with his female agents and with the wives of his male agents. At a party organized by one of his agents, Georg S. allegedly rapes the agent’s ten-year-old daughter and a friend of hers. The father and brother of the victim confirm the rapes to CORRECTIV. The crime is never reported.

Putin is impressed by Georg S. He is strong – and despite his escapades, unconditionally loyal. Two things Putin values highly. Even then, Putin is willing to excuse anything as long as the person stays true to him, says Zuchold. Accordingly, Putin gives Georg S. a full set of hunting gear along with a saber for his 40th birthday.

On the other hand, Georg S. feels superior to Putin. Again and again, he boasts to Zuchold that they will make a proper Chekist (Russian spy) of Putin. Georg S. speaks openly with Zuchold on vacations and at parties.

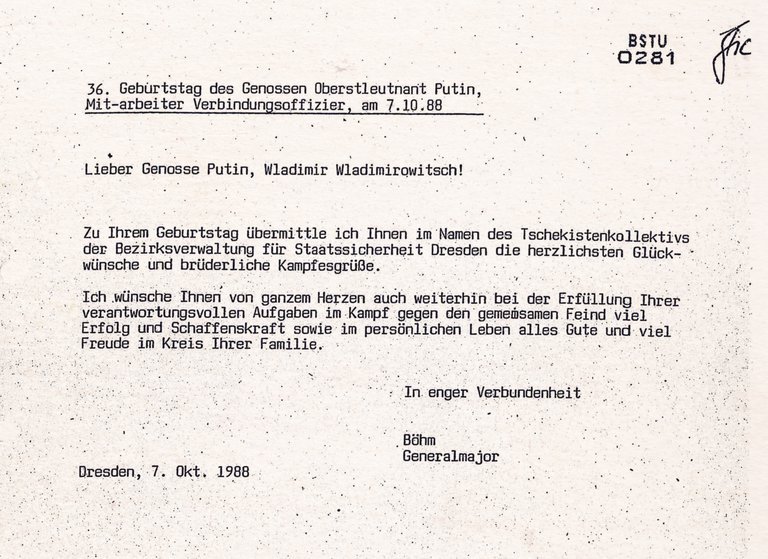

Happy 36th birthday

A two-star Stasi general wishes Comrade Putin best wishes for achieving his important goals in the battle against their common enemy. Dresden, 7 October, 1998

And so we also know about this episode:

Putin wants to obtain information from a professor of medicine by any means. The professor has access to highly sensitive information: a study on deadly poisons that leave hardly any trace – a comprehensive guide for silent killing. The methods range from fake suicide to the use of radioactive materials. Even arsenic poisoning transmitted via a penis during sexual intercourse is discussed in the study.

Putin is highly interested in the study, says Zuchold. And to get it he has different options for winning cooperation: idealism, money or blackmail. To get to the professor, Putin appears to choose „kompromat“ – the planting of compromising material.

According to Zuchold in an interview with CORRECTIV, Georg S. orders him to obtain pornographic material from the Stasi archives. This is to be planted on the professor to blackmail him. Georg S. is merely following orders – the command for this operation could only have come from Putin.

We found the professor from Dresden and asked him if he was blackmailed with pornographic material. He denies the episode.

But in 1993, police investigators found the pornographic material in Georg S.’s bedroom during a raid – it is the same material that was used to blackmail the professor, according to Zuchold who says he was shown the search inventory list. A spokesperson for the police says in response to an inquiry that the files from this case are no longer present.

One of Putin’s most interesting operations is his handling Rainer Sonntag as a KGB agent. Sonntag was a notorious neo-Nazi known throughout East and West Germany. The neo-Nazi and small-time criminal is recruited by Georg S. in the 1980s; this makes Putin responsible for overseeing control of Sonntag. Since Putin is tasked with finding agent multipliers, it is Sonntag’s job to expand the agent network with people he knows such as members of the neo-Nazi movement.

In 1987, Sonntag is deported to West Germany and makes a career as a close confidante to the neo-Nazi leader Michael Kühnen. An agent subordinate to Putin could only be deported with his permission. Sonntag is now an „agent in the field of operations“, meaning a spy in West Germany. He maintains contact to Georg S. and via him to Putin.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall Sonntag returns to East Germany, according to Zuchold. At the border crossing by Hirschberg, Sonntag asks to be picked up by his control-officer Georg S. Back in Dresden, Sonntag helps organize the East German neo-Nazi scene. His return helps the far-right movement in Dresden quickly gain traction.

Sonntag becomes the head of a vigilante group. Together with skinheads in combat boots, he terrorizes street scammers and small-scale criminals. And he blackmails the flourishing brothel business.

Files at the Saxony state police do not shed light on the neo-Nazi Sonntag’s alleged KGB affiliation nor on the full role of Georg S. But since the state police was only founded after reunification, the files could be in another department, says a speaker for the Saxony state police in response to an inquiry. By the editorial deadline, this search remained fruitless.

Sonntag is shot dead in the summer of 1991. His enemies in the brothel business are not the only ones to breathe a sigh of relief. Also Georg S. He later tells Zuchold that Sonntag’s death was best for everyone.

What became of the people?

In 1989, the GDR falls apart. The Soviet Union implodes. And Putin’s work in Germany ends with a failure. We know this from Werner Grossmann, the last head of the GDR foreign espionage service, part of the Stasi. Grossmann warns his colleagues at the KGB that Putin is recruiting GDR agents who have already had their covers blown, creating a high risk for the KGB.

Putin is then suddenly called back from Dresden in February 1990.

Putin is worried about his future. He confides in his colleague Usoltsev, saying that he is afraid he will have to go back to Leningrad, which will soon be called St. Petersburg, and get by as a taxi driver. But he has no reason to be worried. Putin’s KGB contacts prove to be a springboard for an unprecedented career.

And Zuchold changes sides once again. On 26th December 1990, he goes to the West German intelligence service and spills the beans on Putin’s network. The agency refused to confirm the meeting with Zuchold. According to a spokesperson, the agency does not provide information about its contacts or its operations.

Today, Zuchold works for a security company.

After German reunification, Georg S. cannot break with his past. His time of glory is over. He is arrested in on 23rd April 1993. The authorities search his home. They come across the pornographic blackmail material without realizing its significance. It is just listed in the search inventory.

But then something unexpected happens: Georg S. is never charged with espionage. To this day, it is unclear why.

Georg S. never talks to the press. He gets by as a private investigator in Dresden. Sometimes he has a lot of cash, says Zuchold.

In 1999, the year when Putin is named the Russian Prime Minister, Georg S. is brutally beaten on his head with an iron rod in his apartment. Georg S. let the perpetrators inside. He is found unconscious three days later. After that, Georg S. is a wreck. He can no longer concentrate. In conversation, he randomly starts to giggle or cry. He falls into alcoholism and welfare.

One day, Zuchold visits S. in Dresden. Zuchold says they are burned-out birds that nobody needs anymore. Georg S. disagrees. He is still needed. Zuchold tries to convince Georg S. to move to Moscow. He tells S. that he lives on welfare in Germany, while Russia would take care of him thanks to Putin and the old connections. But when Zuchold buys Georg S. a train ticket to Moscow, S. never takes the trip. Georg S. seems to be afraid of travelling to Putin’s country. Later Zuchold suspects that after his arrest, Georg S. might have informed German investigators about Putin’s role in Dresden.

In his last years, Georg S. spends most of his time drinking beer in an Irish pub in Dresden, says Zuchold. Georg S. dies in 2010 at the age of 62. At the funeral, Putin’s former agents meet for the last time. Silently they stand by the open grave. Their former boss does not show up.

What happened to Putin

Putin was married to Lyudmila from 1983 to 2014. The time in Dresden is formative for Lyudmila, since then she has had a special liking for all things German. Back in Moscow, she keeps in contact with her German girlfriends. She sends her daughters to the German school in Moscow. She has fond memories of her time in Dresden.

Memories of her marriage to Putin are less fond. He treats her with disrespect, she complains to one of her pen pals.

Once when Zuchold visits Putin at his home, Putin introduces his wife to the Stasi officer with the following words: she is like a Russian cake – you put lots of sugar into it and it rises. When the men start talking about work, Putin sends his wife to the kitchen because she is not allowed to participate in serious conversations. We asked Putin and his former wife Lyudmila Putina for comment via the Russian Presidential Office. Neither of them have responded.

In the late 1990s, Lyudmila uses the offices and fax machine of the head of the Dresdner Bank in Russia. She uses the fax to keep in contact with her girlfriends. The head of Dresdner Bank in Russia is Matthias Warnig, an old acquaintance of Putin’s. One of his colleagues says Warnig worked as an agent recruiter for the East German Ministry for State Security. In response to an inquiry by CORRECTIV, Warnig’s office responds that he is „not aware“ of Ms. Putina having used his fax machine. In response to the question whether he is an „old acquaintance“ of Putin’s, his office writes: „We cannot qualify the term ‘old acquaintance’.“ Warnig denies that he recruited agents for the Stasi.

Today, Warnig works for Nord-Stream, the company that operates the Baltic See pipeline from Russia to Germany. Former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder (Social Democratic Party Germany) sits on the supervisory board of the same company.

In 1994, Lyudmila Putina has a car crash in St. Petersburg and is badly injured. The Dresdner Bank finances her transportation to Germany and her treatment in a special clinic in Bad Homburg. Bernhard Walter, the former board spokesman for the bank, later says in an interview that he took on Ms. Putina’s costs for „humanitarian reasons“. Because the hospitals in St. Petersburg could not have treated these types of injuries at the time.

During his 2000 presidential campaign, Putin makes no mention of this humanitarian act. He merely says that his wife was treated in a military hospital in St. Petersburg.

The Dresdner Bank allegedly showed Putin its gratitude and paid for some of his trips to Germany. Through a spokesman, Warnig says he has no knowledge of such payments.

People sugarcoat their past; that is not unusual. But Putin goes unusually far. In his official autobiography „First Person“, Putin says that his family was on vacation at the Russian Baltic Sea in 1998 when he learned he has been named as head of the intelligence service FSB.

In reality, Putin and his family spent their vacation in the south of France. This is documented in letters from Lyudmila Putina that CORRECTIV has reviewed. According to a letter Lyudmila writes to a friend, Putin himself commutes between Moscow and southern France for important meetings in July 1998. In August they planned to continue their vacation in Switzerland, in the swank town of Davos. But as a result of Putin’s promotion to head of the domestic intelligence service, FSB, they have to go back to Moscow.

They already know Davos. „We have spent two vacations here with the Shamalov family, six weeks altogether“, writes Lyudmila Putina to her friend in early 1997 from Davos, the Swiss ski resort. The letters were sent via fax. Niklai Shamalov is a wealthy businessman from St. Petersburg with a close relationship to Putin. Lyudmila tells her friend that Putin had done a lot for the Shamalov family, and now they had to do something for Putin. Shamalov and Putin have not responded to inquiries regarding their mutual business relationship.

Meanwhile, Putin rises up to become the most powerful man in Russia while his father is diagnosed with acute cancer. Lyudmila Putina describes the suffering in a letter to a friend in July 1998:

“His father has already been in the hospital for a month, he has cancer, stage IV. The doctors that treated him before missed the onset of the illness, because he always had back pains, and they prescribed him massages, injections, but that was already cancer and metastases! in the spine.“

The doctors do not recognize the cancer. The hospitals in St. Petersburg lack modern medical equipment. As deputy mayor, Putin was also responsible for foreign investments into the city’s health care sector. But there is corruption. A doctor writes that the hospital management turned down cheaper but fully functional used equipment and bought much more expensive new equipment to rake in the customary bribes, according to the email reviewed by CORRECTIV.

Limited reserves are wasted. In the end, the man whose son helped build this system fell victim to it.

Like this story? Support independent journalism with your membership. Become a member of CORRECTIV.

Putin week at CORRECTIV

German-English Translation: Noah Walker-Crawford

Copy Editor: Ariel Hauptmeier

In Cooperation with RTL und Mediapart.