“With a few simple steps“: How RT DE circumvents the EU sanctions

In March the EU banned Russian broadcasters. Among them RT, formerly known as Russia Today. Since then, its German version RT DE has been advertising digital loopholes to work around its suspension. Above all: mirror pages, dozens of them. Why have the responsible German authorities not managed to shut them down?

Lavrov: Footage from Butcha is an anti-Russian staging.

Dmitry Medvedev: Nazi regime in Ukraine must be dismantled.

Russia begins liberation struggle against Ukrainian occupation.

Kremlin spokesman Peskov: Ukraine threat of a ‘dirty bomb’ is real.

Headlines like these are meant to justify Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. They are propaganda, published in German by Russian broadcaster RT. Propaganda that was banned in the European Union a few days after the war began. Content from Russian broadcasters poses “a significant and direct threat to the order and security of the EU,” a European Commission spokesman tells us to justify the measure.

EU member states are to implement the sanctions on their own. They shall ensure that websites of sanctioned Russian broadcasters can no longer be accessed. In Germany, Internet providers block content based on a list provided by the Bundesnetzagentur (Federal Network Agency). An incomplete list compiled by the agency based on irregular monitoring, our research shows. What is more, users can bypass the block “with a few simple steps,” according to an IT expert.

Looking at what RT’s German version, RT DE, has been up to since the suspension, unveils just how patchy the implementation of the sanctions is. RT DE published articles with the above headlines on so-called mirror pages – copies of RT DE‘s original website. All of the articles were published after the sanctions were imposed. To date, we have been able to access them in Germany on several sites – without any problems, and even after we had inquired about the sites with the Bundesnetzagentur on October 20. We found dozens of these pages in recent months.

The mirror sites are just one of several digital loopholes RT DE uses to circumvent the EU ban. So, how useful are the sanctions against Russian propaganda on the Internet?

Sanctions: Several Russian channels banned across EU territory

“Sputnik and Russia Today are under the permanent direct or indirect control of the authorities of the Russian Federation and are essential and instrumental in bringing forward and supporting the military aggression against Ukraine, and for the destabilisation of its neighbouring countries,” the Council of the EU wrote in a press release on March 2, 2022. Words with consequences. The Council used them to justify the suspension of the two Russian broadcasters. In June three other channels followed: Rossiya RTR / RTR Planeta, Rossiya 24 / Russia 24, and TV Centre International.

“The regulation essentially bans the ‘broadcasting activity’ of the sanctioned media, which includes the distribution of content through broadcasting and on the Internet,“ lawyer Björnstjern Baade, a research associate in the Department of Public Law at Freie Universität Berlin, explains. It covers all means of transmission from cable to websites and satellite to apps.

The ban is not the first suspension of Russian media: in 2016 and 2021, Lithuania and Latvia blocked Russian broadcasters RTR Planeta and Rossiya RTR for several months for inciting violence and hatred. Lithuania also blocked RT in 2020. However, a EU-wide ban is a first, Baade says.

RT‘s French version RT France took legal action against the suspension. Unsuccessfully. The European Court of Justice rejected its plea for annulment at the end of July. Decisive was, according to Baade, the court’s reasoning that the media supported a war in violation of international law; a war which had been clearly condemned by the United Nations General Assembly. Support for the war by the media constitutes war propaganda and can therefore be prohibited, he explains. In its ruling, the ECJ describes the restriction of freedom of expression as proportionate in this case.

But, “RT DE wouldn’t be RT DE if we didn’t have solutions!“ the channel confidently declares on its website.

How can entire websites be blocked?

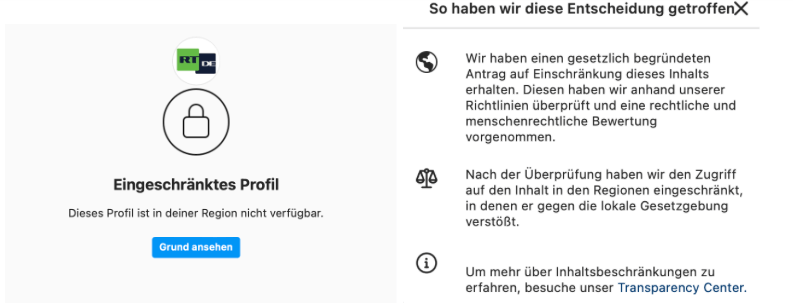

RT DE has been banned from major social media platforms Facebook, Instagram, Tiktok, Twitter, YouTube and even Telegram in Europe. As far as its website is concerned, there are loopholes – RT DE has the “right formula“ to get around the sanctions.

On its website and via its newsletter, the channel advertises various solutions and features handy explanatory videos. A virtual private network (VPN), for example, can bypass the country block by allowing cell phones or computers to access content virtually via a non-EU country.

However, the simplest solution, RT DE stipulates in a newsletter, is to bypass the so-called DNS blocking. It’s the main tool used to block access to websites.

What is DNS blocking?

DNS stands for Domain Name System. It assigns website addresses (for example, rt.com) to an IP address, explains IT expert Jochim Selzer from the European hacker collective Chaos Computer Club. This requires so-called name servers. The system is comparable with a telephone directory, in which the corresponding IP address is stored for each domain.

With DNS blocking, the state usually approaches Internet providers and asks them not to answer requests to a web address, Selzer says. Consequently, one can no longer open the webpage. By use of the directory analogy, this means that a phone number is deleted from the phone book and can no longer be found. In the case of DNS blocks, entries of the affected websites are deleted from the name server.

In general, DNS-blocks violate the principle of equal treatment of all data traffic (network neutrality), writes the Bundesnetzagentur. But there are exceptions that justify a block, such is the corresponding EU regulation applicable in Germany. The Bundesnetzagentur examines whether a block is lawful and meets network neutrality requirements.

In Germany, the blocking of the corresponding Russian websites works as follows: the Bundesnetzagentur provides lists of websites that can be blocked to digital associations (such as Bitkom). These pass the information on to their members – Internet providers such as Telekom, Vodafone, 1&1.

However, these lists are not an instruction – the decision whether to block or not lies with internet providers, the Bundesnetzagentur emphasizes in an email to the associations dated June 27, 2022. Several emails about the matter were published through a freedom of information request by “Frag den Staat”. This specific message was about the blocking of the domains of Rossiya RTR / RTR Planeta, Rossiya 24 / Russia 24 and TV Centre International from June 25 onwards. Accordingly, it’s okay to block entire domains (such as rt.com) rather than just individual articles. By doing so, “the EU accepts that this blocking might also result in the potential blocking of legal content” the Bundesnetzagentur writes.

Loopholes to circumvent the sanctions: RT has the “right formula”

DNS blocks are not very effective. They essentially only keep content away from those who have no interest in it anyway, says IT expert Jochim Selzer from European hacker collective Chaos Computer Club: “Everyone else knows how to get around these blocks with a few simple steps.” Instructions and How-tos abound online.

Hermann Lindhorst, a lawyer specializing in IT and media law, also thinks: “Internet blocks should always be questioned, firstly from a purely practical point of view and because of fundamental rights. Secondly, they are not only easy to circumvent, there are other alternatives.”

Timeline: From RT‘s founding to its ban

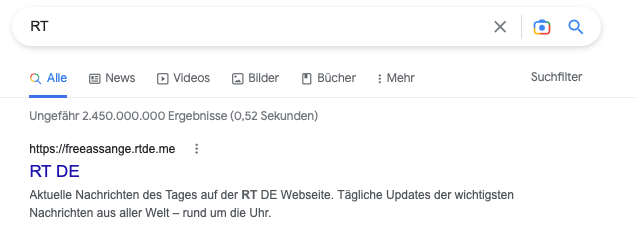

RT DE relies on precisely these alternatives and promotes so-called mirror domains: copies of RT’s website, which can be reached via other web addresses. The mirror domains have “rtde” in their address, but instead of common domain extensions like “.de” for Germany or “.com” they use extensions such as “.tech” or “.life”.

IP addresses of the alternative RT websites point to two Russian companies – one of them is RT’s parent company

We found nine different German mirror domains. On top of that: sub-domains whose addresses have the same extension but different beginnings (for example, meinungsfreiheit.rtde.life). A query via Whois shows they were created on March 5 and April 6, 2022, all after the suspension – a clear indication that they were intended to bypass the ban.

Our search returns two IP addresses who point to servers of two Russian companies: ANO TV-Novosti and PJSC Rostelecom. The former was founded in 2005 by the Russian state news agency RIA Novosti. ANO TV-Novosti produces RT‘s foreign-language channels; it is listed in the legal notice of both the official RT website and current mirror pages. PJSC Rostelecom is Russia’s largest telecommunications provider, a corporation most of whose shares are owned by the Russian state.

Mirror pages are not only meant for German audiences – they also target Spain or France

RT’s efforts aren’t limited to Germany. There are various mirror domains in multiple languages, but the main focus seems to be on German content. In a report from October, the UK-based Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) documented a total of 19 RT domains: nine German, seven Spanish, two French and one English. “It seems to us that the focus is on German and Spanish audiences,” analyst Kata Balint, who was involved in the report, tells us.

A systematic approach? “Almost all [of the sites], when you could get information, were registered on the same day or the same chunk of days and broadly within the same two hours,” Jordan Wildon, senior digital methods manager at ISD, says. To Wildon, it seems RT was experimenting with what worked and how to get around the blocks.

Archived versions of its website show that RT DE was indeed reactive to the suspension. In April, it stated, while referring to its workaround pages: “These older links may no longer work.” They saw blocking of “alternative addresses” by Telekom, among others.

“Review takes place at irregular intervals”: How the blocking works in Germany

So why is the implementation of the sanctions so patchy? The published emails from the Bundesnetzagentur shed some light. The information passes through a number of institutions: the Bundesnetzagentur compiles the lists, but emphasizes it is only responsible for monitoring the net neutrality requirements – it is the “entrepreneurial decision” of the associations in the telecommunications sector whether or not to block the websites.

The associations – Bitkom, Eco, Anga and Vatm – in turn told us that they merely forward the information to their members (Internet service providers). Enforcing and monitoring the blocking is not part of their tasks, they say.

So in the end, it is up to Internet providers to implement blockings; they are obliged to do so by the EU regulation. As major German Internet providers Telekom, 1&1 and Telefónica / O2 explained to us: they work almost exclusively on the basis of the lists supplied by the Bundesnetzagentur.

“We work closely and well with the Bundesnetzagentur,” 1&1 writes, adding that a block always requires a dialog with the federal agency. Similarly, Telekom notes: “Telekom Deutschland blocks (…) access to the defined and specified websites after approval by the Bundesnetzagentur.” Accordingly, the Internet providers do not check the content of the announced pages. Teléfonica writes that the implementation is based on lists from the Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications (BEREC) and the specifications by the Bundesnetzagentur.

In principle, this process makes sense. Internet providers can thus rest assured that they are not blocking excessively and unlawfully. However, in order to find mirror sites and workaround pages from RT, the Bundesnetzagentur would have to actively search for them and update its lists accordingly. This seems not to be the case.

When asked how the lists come about, the Bundesnetzagentur has a sobering answer: “A review is carried out at irregular intervals by employees of the Net Neutrality, Platform Monitoring, Artificial Intelligence department. It is a – not necessarily exhaustive – Internet search for corresponding content that must be blocked due to the EU sanctions regulation.” In part, the information is also based on requests from individual Internet access providers or third parties. There are exchanges at the European level, primarily with the European body for electronic communications BEREC, the agency notes.

The Bundesnetzagentur does not tightly monitor websites – and neither does anyone else

As the email exchanges show, the Bundesnetzagentur did respond to the mirror sites advertised by RT DE. At the beginning of April, it drew attention to three domains. More followed at the end of April. Currently, these websites can’t be accessed.

The published emails from the Bundesnetzagentur to the telecommunications associations date back to the end of July; we don’t know if more followed after. Neither the federal agency, the associations nor the Internet providers were able or willing to provide us with a list of all the websites that have been blocked so far.

The Bundesnetzagentur admits: “The instrument of mirror domains is one of the weak spots in DNS blocking.”

In order to block content continuously, tight monitoring is necessary. Such monitoring is not carried out by the Bundesnetzagentur. – Bundesnetzagentur

In its response to us, the Internet provider 1&1 points out that there might be some delay in blocking “fast-changing” mirror pages.

But, the advertised websites don’t seem to be fast-changing: RT DE has been advertising the same mirror pages since at least May. We were able to find several domains and subdomains that are still online. Why and how they slipped through the Bundesnetzagentur’s monitoring is unclear. In response to our inquiry on October 20 as to whether the websites in question were known, the agency announced that it would “include the domains listed in the Bundesnetzagentur’s next communication to associations in the telecommunications sector.” So far, this does not seem to have happened.

And the federal government? Seems to have little to do with controlling the EU ban. When asked, the Federal Ministry of Economics refers us to the public prosecutors’ offices; they are accordingly responsible for prosecuting sanctions violations.

RT‘s content reaches European audiences – first and foremost German ones

One thing is certain: Content from RT continues to reach European audiences, and quite broadly so. According to the report by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, the 19 identified RT domains generated more than 11 million visits between April and June. Most impressively, numbers from June showed that visitors to the German-language alternative domains were indeed accessing content primarily from Germany, it says in the report. The numbers cannot be independently verified. It is also true, according to the ISD, that RT‘s overall reach has declined compared to before the war.

The ISD also noted that referrals to RT domains via Whatsapp and Telegram had increased, which is “quite problematic,” Kata Balint finds. A look at German-language Telegram channels, which our fact-checking team monitors, confirms that alternative websites are circulating there. Channels with names such as “German-Russian Friendship,” but also anti-vaccination groups such as “Vaccine Criticism” or conspiracy followers at “Q&Anons” shared dozens of links to the mirror pages.

RT knows how to move between the lines of implying and providing misinformation in its reports. It often quotes people and their false statements. Thus, RT does not make the claim itself – but the message sticks, like the statement about an alleged staging of corpses found in Bucha, or that Ukraine is allegedly ruled by a Nazi regime. What’s more, RT has also been spreading misinformation since the war began, as was the case in August, when it claimed Ukrainian deputies had allegedly received a 70 percent salary increase. The article appeared on a mirror site called test.rt.me (we reported).

As the ISD wrote in another report in July, RT‘s articles also sustain familiar narratives that negatively depict Ukrainian refugees. Among them: the alleged favoritism of Ukrainians over other refugees, the high cost of hosting them, and violence and aggression emanating from refugees. Oftentimes, these allegations are simply fabricated, as we reported in our fact-checks (see here, here und here).

What good are technical sanctions to tackle disinformation?

Our research shows that RT DE circumvents the broadcasting ban in the EU with very simple means. So, how useful are bans to tackle disinformation?

“It’s never a good idea to try to solve societal problems through technical means,” says IT expert Jochim Selzer. Media law expert Hermann Lindhorst agrees: “In my view, these things need to be solved socially, and not through repressive Internet blocks, which aren’t difficult to bypass anyway.”

Despite the ban, Germans seem to be more receptive to pro-Russian propaganda, a report published in November by the Center for Monitoring, Analysis and Strategy (Cemas) shows. It found that approval ratings for pro-Russian conspiracy narratives have risen among the German population since April 2022. One can only solve this problem through socio-political debates on how to counter increasing disinformation campaigns, Cemas writes. Understanding disinformation solely as an information or security problem falls short, it notes: “It’s an attack on democracy as such.”

Switzerland and Norway, both not members of the EU, have decided not to block RT and Sputnik. The Swiss Federal Council argued in March: it is “more effective to counter untrue and harmful statements with facts rather than to ban them.”

Editing: Alice Echtermann, Matthias Bau

Data analysis: Sebastian Gurkasch

This article was first published in German on November 10, 2022. You can access the German version here.