Reports of sexual violence in the war: Why the Ukrainian parliament dismissed Human Rights Chief Denisova

The Ukrainian parliament dismissed Human Rights Chief Lyudmila Denisova amid claims that she spoke unethically about rape and sexual violence committed by Russian soldiers against Ukrainian civilians. Some German-language websites accuse her of inventing cases all together. What truth is there to these accusations?

Warning: The following article contains descriptions of sexual violence that readers might find upsetting.

On May 31st, the Ukrainian parliament dismissed Lyudmila Denisova, who was, up to that point, the appointed Human Rights Chief. German and international media had often cited her graphic accounts of sexual violence and rape committed by Russian soldiers against Ukrainian civilians. Denisova’s accounts were disturbing and covered the rape of infants, two dozen women who were repeatedly and systematically raped in a basement, or the abuse and torture of a man who had left his hideout to fetch some water.

In Ukraine, media professionals and human rights activists criticized Denisova and deemed her language inappropriate and unethical. But the allegations extend beyond this criticism, fueled by Russian and German websites that have reported on the war against Ukraine from a pro-Russian perspective for weeks: Did Denisova invent the reports of sexual violence she made public?

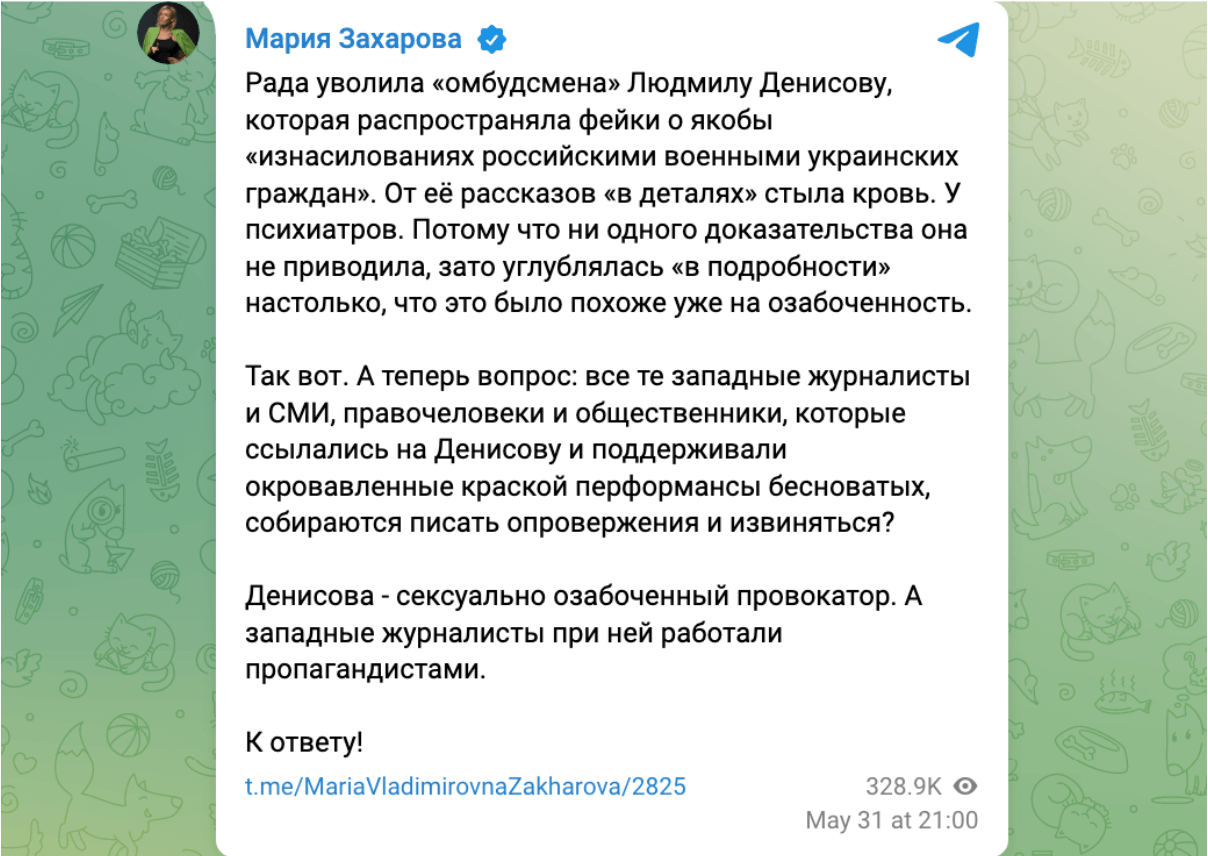

Right after her dismissal, Maria Zakharova, spokeswoman of the Russian foreign ministry, claimed in a Telegram post that Denisova was sacked for spreading false reports about „alleged rapes of Ukrainian citizens by the Russian military.“

German websites echo Russian narratives of allegedly invented rape cases

German websites picked up on this narrative shortly after. The Nachdenkseiten’s headline read: „Ukrainian human rights commissioner removed over fabricated ‘mass rape’.“ The text claims that Denisova „simply made up most of the descriptions“ and was therefore dismissed. Report 24 had similar reporting. The Anti-Spiegel even claimed: „All reports of rapes by Russian soldiers were fictitious.“

We spoke to Ukrainian and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) about documented cases of sexual violence in Ukraine. We asked them and organizations of the United Nations (UN) about their collaboration with the former Human Rights Commissioner. Lyudmila Denisova did not comment on or respond to our queries.

Our research unveils legitimate doubts about the cases Denisova published on her social media accounts and talked about with the media. It remains unclear how many cases actually took place. Although the UN encouraged her to do so, Denisova did not send any supporting evidence to the UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine.

That does not mean that Russian soldiers have not or are not committing sexual violence against Ukrainian civilians over the course of the war – several organizations have documented and investigated cases. But the allegations against Denisova have far-reaching consequences: Russian propaganda can use them to further deny that its soldiers are committing war crimes in Ukraine.

How Lyudmila Denisova was dismissed

On May 31st, a majority of the Ukrainian parliament voted in favor of removing Denisova from office. The ruling party, Servant of the People, to which President Volodymyr Zelenskyj belongs, initiated and announced the dismissal.

Ukrainian MP Pavlo Frolov wrote in a Facebook post that Denisova had neglected her duties by not setting up humanitarian corridors or advanced prisoner exchanges. Instead, she had focused too much on graphically outlining cases of sexual violence for which she did not provide any evidence. That, according to Frolov, harmed Ukraine’s reputation.

Websites point to an interview with Denisova where she allegedly admitted inventing cases

Nachdenkseiten, Anti-Spiegel and Report24 refer to an interview with Denisova that took place a few days after her dismissal. They say it is proof that Denisova made up cases, by „admitting“ that her statements about sexual violence „could be fabricated,“ as Report24 writes.

The interview in question was published by the Ukrainian news site LB.ua on June 3rd. In it, Denisova admits to being too graphic in her descriptions. Maybe she „exaggerated,“ to shake up the world regarding the events in Ukraine. The vocabulary she used was „harsh“ but she only repeated what psychologists who worked at her hotline told her.

Denisova did not say she invented cases.

Human rights groups and media representatives openly criticized Denisova for her language

Ukrainian media professionals, human rights defenders and psychologists already criticized Denisova at the end of May in an open letter. The letter states that publishing „shocking details“ must be justified and appropriate, especially when it comes to children. Sexual violence is a difficult and traumatic topic for families, not a topic meant for a „scandal column.“

The letter was co-signed by Tetiana Pechonchyk, Chairwoman of the Ukrainian human rights organization Zmina. According to Pechonchyk, the intent behind the letter was not to get Denisova fired, but to point out how unethical Denisova’s wording was. However, the scandal comes as no surprise to Pechonchyk. Human rights organizations had criticized Denisova’s election as Human Rights Commissioner from the beginning, lamenting that they and the public were not involved in the candidate’s selection. As a former member of parliament, Denisova was not impartial enough, says Pechonchyk. The latter’s organization has therefore greatly limited working with Denisova.

Julia Anosova, who works as a lawyer for the Ukrainian human rights organization La Strada, is equally critical towards Denisova’s language. In an interview with CORRECTIV.Faktencheck, Anosova outlined that her organization has strict standards and publishes details only after thorough consultation with those affected. La Strada operates a hotline for domestic violence and human trafficking; reports of sexual violence have increased since the beginning of the war, Anosova said. Those seeking help are often in „devastated psychological conditions.“ Urging them to publicly share their experiences could be „manipulation;“ the interests of those affected should prevail over the interest of the state.

Investigation by Ukrainian website Ukrainska Pravda reveals inconsistencies in Denisova’s statements

The question stands: Are the cases of sexual violence brought forward by Denisova actually true? The allegations revolve around a special hotline launched by Denisova’s ombudsman office on April 1st, which Denisova claims is the source for her reports. According to the Ombudsman’s website, the UN’s children fund, Unicef, supported the project. In some instances, Denisova described the hotline as a project run by Unicef – which the UN organization denied upon our inquiry: According to Unicef, they only provided technical support and equipment.

Denisova stated in an interview that the hotline was meant to provide psychological support for those affected. The hotline received many reports of sexual violence and she passed on „word for word“ what the psychologists working there had told her.

That is questionable, according to an investigation by Ukrainian online newspaper Ukrainska Pravda. Five people supposedly worked at the hotline. One of them is Denisova’s daughter: Oleksandra Kvitko.

Denisova rejected claims of nepotism in an interview. Unicef had hired the hotline’s psychologists through a partnering NGO. However, Unicef told us that it had not hired any staff for the ombudsman’s office.

Denisova said her daughter told her about the cases of sexual violence

According to the investigation by Ukrainska Pravda, during interrogations by the public prosecutor’s office, Denisova admitted that she obtained information on sexual violence from her daughter, Oleksandra Kvitko. She no longer knew whether she also spoke to other psychologists. Like her mother, Kvitko revealed harrowing details of cases of sexual abuse and rape in interviews with the media.

Tetiana Pechonchyk explained that hotlines also play an important role in Zmina’s work because they present a low-threshold entry point for those affected. The main problem with the former Human Rights Commissioner’s hotline is however, that the public does not know whether people have actually reported the cases in question: „Maybe people really told these stories, maybe not. The problem is, we don’t know.“

The report by Ukrainska Pravda reveals further discrepancies: Denisova’s daughter told the prosecutor’s office that she had received 1,040 calls via the hotline, 450 of which concerned the rape of children. But an official log showed only 92 calls were made.

According to the newspaper, neither Denisova nor her daughter commented on the allegations. Denisova also did not respond to multiple inquiries from CORRECTIV.Faktencheck.

Authorities and UN organizations apparently never received any documents from Denisova

It not only remains unclear how exactly the former Human Rights Commissioner obtained the information she later publicized, but also whether she ever handed over relevant documents to authorities.

Ukrainska Pravda quotes three anonymous sources who say that Denisova did not pass on any records about the cases she made public to law enforcement agencies.

Similarly, the Ukrainian Prosecutor General Iryna Venediktova told a correspondent of the Ukrainian news outlet Babel that Denisova did not provide her with any material on rapes.

On June 3rd, after her dismissal by parliament, Denisova wrote about a meeting with Matilda Bogner, on Facebook. According to Denisova, she and the head of the UN human rights monitoring mission in Ukraine talked about the results of their „fruitful cooperation.“ Bogner’s office wrote to CORRECTIV.Faktencheck that so far it had not received any referral cases of sexual violence from Denisova, although they had „encouraged“ her to do so.

On May 23rd, Denisova’s office published multiple accounts of alleged deadly cases of rape against children and adolescents. They appealed to Pramila Patten, the UN Secretary-General’s special envoy on sexual violence in conflict, to investigate the cases. However, these investigations never took place, a spokeswoman for Patten told us. Why, we asked? They never received any material from Denisova, the spokeswoman said.

Reports from the UN and non-governmental organizations corroborate cases of rape and sexual violence against children

The allegations against Denisova weigh heavy and sow seeds of doubts. According to Tetiana Pechonchyk, they „have become a weapon for Russian propaganda“ which allows Russia to claim „that Ukraine made up all the atrocities or all the information about sexual violence.“

The spokeswoman of Russia’s Foreign Ministry, Maria Zakharova, picked up on the allegations right after Denisova was dismissed. She described Denisova as a „provocateur“ and journalists who featured her reports as „propagandists“: „Will they retract their claims and apologize?“

Notwithstanding the doubts about Denisova’s reports, they are not proof that Russian soldiers did not or are not committing sexual violence in Ukraine, as several organizations have documented. On June 6th, during a session of the UN Security Council, Pramila Patten spoke about 124 reports of alleged incidents of sexual violence: including rape, attempted rape, forced undressing and threats of sexual violence. The cases are still being verified.

The UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission reported cases in Kyiv’s suburbs back in May. Employees visited 14 cities in the Kyiv and Chernihiv regions and spoke to locals who told them about sexual violence against civilians. A report from June 29th stated the Monitoring Mission had confirmed 23 cases of sexual violence, of which the majority was committed in Russian-controlled areas. According to Bogner, many of those affected are afraid of the stigma surrounding sexual violence and are reluctant to talk about their experiences.

The anonymity afforded by their hotline is probably the reason why those affected feel confident enough to report cases, Julia Anosova highlighted. La Strada’s hotline has, so far, received 15 rape reports committed by Russian soldiers, affecting all genders, children and adults, she said. The youngest person was 12 years old, the oldest 50 years old. Reports by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch include testimonies of similar cases.

On July 19th – after the initial publication of our investigation – the Ukrainian public prosecutor’s office informed CORRECTIV.Faktencheck that, so far, 35 victims of sexual violence had been identified. Two had died and criminal proceedings had been initiated against three Russian soldiers. Information that Lyudmila Denisova had published on her Facebook page was included in two criminal cases. The prosecutor’s office did not specify which cases they referred to.

Denisova’s allegations put Ukraine to the test

Some expressed their outrage after Ukrainska Pravda published their report. Employees of the online newspaper were threatened and accused of supporting Russia. The names of the journalists involved subsequently appeared on a ‘list of enemies’ of Ukraine.

Still, Tetiana Pechonchyk believes that investigating these allegations is the right move. She thinks it is important to „publish the truth during the war,“ as it shows that misconduct will not be tolerated.

But it is not just about the country’s public perception, says Julia Anosova. The affair around Denisova could also have other negative effects. The lawyer fears that the allegations might influence other survivors’ willingness to talk about their experiences.

Denisova wanted to shake up the world with her reports. But in doing so, she might have harmed the very people she wanted to protect as a Human Rights Commissioner – those affected by sexual violence.

Note: This article was first published in German on July 15th.