Forged government documents and fake news sites: Russian disinformation campaign targets Germany

A network of fake news sites has been flooding Europe with disinformation and propaganda against Ukraine for months. Reports uncovered websites that mimicked media outlets like Bild and Spiegel. But it doesn’t stop there. Research by CORRECTIV.Faktencheck shows that the Russian campaign also entails forged government documents.

It’s the largest and most complex Russian disinformation campaign since the start of the full-blown aggression against Ukraine: Fake reports about Ukraine spread from more than 60 deceptively real-looking imitations of major media outlets. Among the affected outlets are Spiegel, Süddeutsche, Tagesspiegel, Bild, T-Online and Welt, British outlet The Guardian or the Italian news agency Ansa. The goal is to stir up sentiment against Ukraine and Ukrainian refugees in Europe by spreading fake reports. Several European countries are targeted – first and foremost Germany.

The operation began back in May, but it went undetected for a long time. Journalists from T-Online and ZDF first reported about it at the end of August. Their reports put Facebook’s parent company Meta on track: the company said it identified more than 1,600 Facebook accounts, 700 Facebook pages and 29 Instagram accounts, as well as Telegram and Twitter accounts. They are part of a network which scattered content of the cloned media websites online.

An investigation by CORRECTIV.Faktencheck reveals: the disinformation campaign doesn’t stop there. To fuel the narrative that heavy weapons supplied to Ukraine end up on the black market in Germany, disinformation channels also forge letters from politicians – their origin can be traced back to pro-Russian hacker groups.

A German-language Telegram channel connects two disinformation campaigns against Ukraine

According to Meta, in the early stages of the Russian disinformation campaign a German petition was launched on ‘change.org’. It called for an end to the “unacceptable generosity” toward Ukrainian refugees. As Meta states, the petition was circulated by the same kind of Facebook accounts that had begun to share articles from fake media websites in June.

The small petition only got ten signatures but here’s why it’s important: It advertised a Telegram channel with the username “News_Freies_Deutschland”. An analysis with the Telegram tool TG-Stat shows, the channel was first called “Freies Deutschland”, then “Journalisten friekorps” and now “Journalisten Freikorps”. The channel was first active at the end of May 2022.

On the outside, it poses as a channel of journalists. Its description sounds platitudinous: “Our task is to help the German state and the German people. The people must be united, Germany must be free.” True, the channel only has around 6,200 followers – but it managed to spread a viral fake in September. Not via a cloned news site, but by use of a manipulated video.

A Telegram post from September 6 claimed that two Stinger missiles had been found on a ship in “Bremen harbor” (a city in northern Germany) but that the missiles were actually destined for Ukraine. Now, the post claimed, they had ended up on the black market. The video was shared by numerous accounts on Telegram and Twitter. We were able to show that the video contained false audio and that the alleged arrests of the Ukrainian smugglers in Bremen never took place.

On September 8, “Journalisten Freikorps” followed up: A Ukrainian radio station had supposedly published “interesting documents” about the case. The post included a letter from Ukrainian Defense Minister Oleksiy Resnikov, in which he allegedly wrote about the weapons that had been found in Bremen. The letter is fake. And it is not the only fake of this kind.

Beyond fake news sites: campaign uses forged Ukrainian and Polish government documents

On June 16, 2022, the Telegram channel “Beregini” shared a letter in which Ukrainian Defense Minister Oleksiy Resnikov allegedly announced that it was necessary to bring back male Ukrainian refugees from abroad due to the acute shortage of soldiers. The letter has the same letterhead date and document number, and except for the text, it looks exactly like the letter about the alleged discovery of weapons in Bremen.

Such official letters from Ukraine really exist. An electronic system creates a unique QR code which is then printed on the bottom left. This QR code assigns a number and a date of creation to the documents. The telltale detail in this case: If you scan the codes of both letters from Telegram, the date “29.04.2022” and the document number “220/3034” show up in both cases. This means, for both fakes, an original document from April had been forged.

Disinformation containing forged documents targeted Poland – and also ended up in Germany via Alina Lipp

The fake documents reveal a pattern that the Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFR Lab) has analyzed. Since June, “Beregini” and another Telegram channel called “Joker DPR” shared several fakes with different content which look like official letters from the Ukrainian or Polish foreign ministries. As DFR Lab’s Givi Gigitashvili tells us, the two channels regularly publish “leaked documents” – and mix them with fake ones.

One example revolves around the false claim that a street in Warsaw was supposed to be named after Ukrainian fascist Stepan Bandera. The alleged proof was a document signed by Polish Deputy Foreign Minister Marcin Przydacz. “Joker DPR” shared it on Telegram on August 17, the post was viewed more than 500,000 times. The same day, Przydacz clarified on Twitter that the announcement was fake. Nonetheless, in Germany, pro-Russian activist Alina Lipp spread the story on her Telegram channel.

“Beregini” and “Joker DPR” are no strangers to each other: The cybersecurity firm Mandiant describes the group behind “Beregini” as “hacktivists” allied with Russia, who have been spreading allegedly leaked letters from Ukrainian military circles for years. The acronym DPR in “Joker DPR” stands for “Donetsk People’s Republic”, which has been ruled by pro-Russian separatists since several years. It’s difficult to uncover the exact identity of the hacking groups, DFR Lab’s Givi Gigitashvili tells us. “But it’s obvious that these actors are trying to undermine relations between Poland and Ukraine, as well as between the U.S. and Ukraine, and trust in the Ukrainian government.”

Whether “Journalisten Freikorps,” “Beregini,” and “Joker DPR” are working together cannot be proven. However, the similar modus operandi is striking.

Speculations about connection to pro-Russian hacking group “Ghostwriter”

Cybersecurity firm Mandiant also concluded in a June analysis that “Joker DPR” and “Beregini,” for their part, could have ties to a pro-Russian hacking group called Ghostwriter, which is close to the Belarussian government. There is no conclusive evidence, but according to Mandiant, the dissemination of the forged documents may have been coordinated with them.

Ghostwriter’s previous campaigns involved hacking social media accounts of Polish citizens and spreading misinformation through them, as DFR Lab also reported. This fits the pattern DFR Lab observed in the summer: the fake document about the alleged renaming of a street in Warsaw was shared on two Facebook accounts that belonged to Polish historians. Again, these appear to be hacks: One of the men told DFR Lab that he did not post the document himself.

Possible connection to Putin’s confidant Yevgeny Prigozhin’s troll factory?

DFR Lab also sees a possible connection to another well-known player: entrepreneur and Putin confidant Yevgeny Prigozhin, who recently publicly admitted to being the founder of the patriotic mercenary group Wagner.

One Russian Telegram channel called “ЧВК Медиа” (“ChVK Media”) most often shares content from the Telegram channels “Beregini” and “Joker DPR”. “An example: ‘Beregini’ published 945 posts between March 2, 2020 and August 18, 2022, and “ChVK Media”mentioned ‘Beregini’s’ posts almost 500 times during this period, starting just one day after ‘Beregini’s’ first post,” DFR Lab’ Givi Gigitashvili explains. According to DFR Lab, “ChVK Media” belongs to the Russian news agency Ria Fan. The news agency, in turn, has ties to the Patriot Media Group and the Internet Research Agency (IRA), which is known worldwide as the largest Russian troll factory discovered to date. Prigozhin is said to be behind both Patriot and the IRA. Prigozhin’s mercenary force is also known as “ChVK Wagner”. ChVK is the Russian abbreviation for a private military company.

None of this is clear evidence that all these actors are cooperating. But the circumstantial evidence is astounding.

“Journalisten Freikorps” systematically built up a story on arms smuggling from Ukraine

Back to “Journalisten Freikorps”: Until the post about the fictitious discovery of weapons in Bremen, the Telegram channel had published only everyday news from Germany. But since the beginning of September, it seems to be pursuing a strategy: two days after the Bremen fake, there were more stories about the alleged arms black market in Germany. The first featured a student in Dresden who allegedly discovered the same kind of Stinger missiles from Ukraine that had turned up in Bremen in an online shop. The student had contacted the Dresden police department with this.

As evidence, “Journalisten Freikorps” shared a photo of a website with weapons, the message from the alleged student “Max” and an email that the student had received from the police. The message from “Max” looks chaotic and contains spelling mistakes. The wording seems awkward, and at the beginning he mentions a last name that is different to the one that can be derived from the email address given on Telegram. However, the Dresden police confirmed to us that a person named Max had indeed contacted the police and that the case was currently being investigated by the State Security Service (Staatsschutz). We also contacted the alleged student, but have not yet received any response.

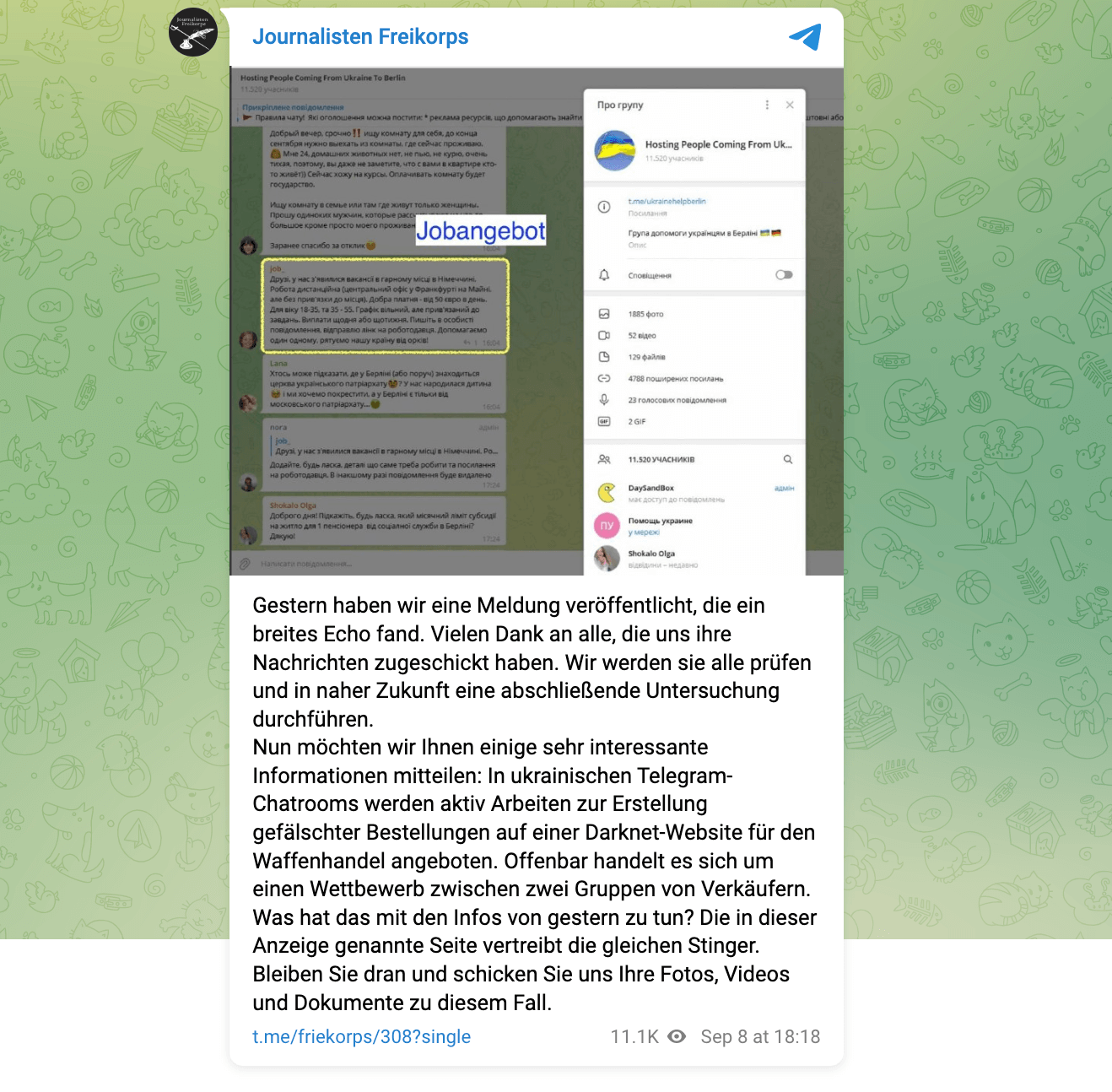

“Journalisten Freikorps” published a second story on September 8. This time it said that they had discovered Ukrainian Telegram chats in which people were being recruited to bid on weapons offered on the Darknet. In the ads they would bid on “the same stingers” – this statement probably refers to the false report about Bremen.

The Telegram channel shares a screenshot from another channel called “Hosting People Coming From Ukraine To Berlin” as evidence. The screenshot highlights a job offer, but the content remains vague. There is talk of telecommuting, a “good salary” and flexible working hours. Anyone who wants to know more about the specific job is asked to send a private message.

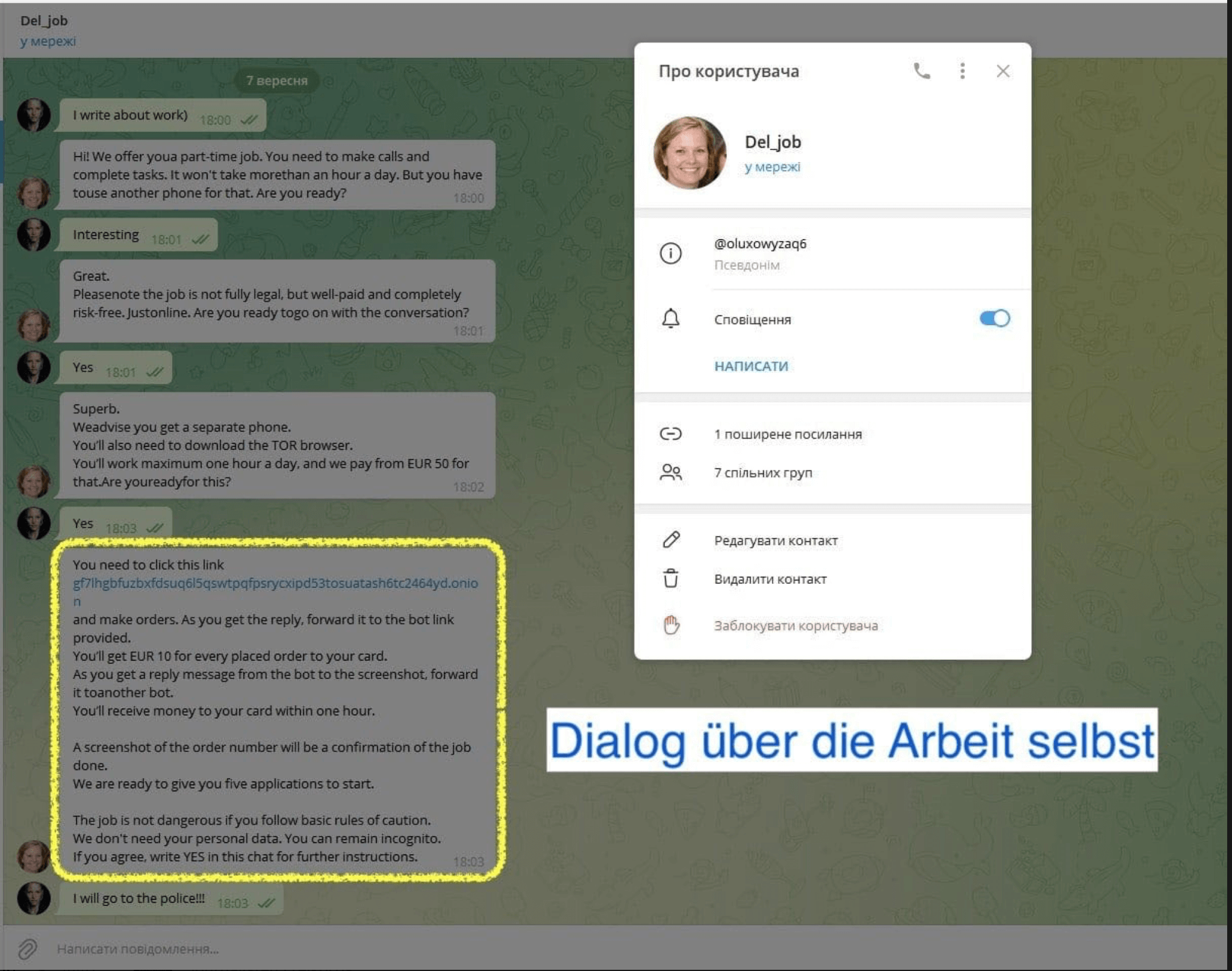

In the Telegram channel “Hosting People Coming From Ukraine To Berlin” we found a message from an account named “Alisa”, who claims to have started a private chat with the provider’s profile in response to the job offer. However, the chat between “Alisa” and the unknown person does not mention weapons from Ukraine.

The job offer itself can no longer be found in the channel “Hosting People Coming from Ukraine To Berlin”; it was apparently removed by an administrator at the request of “Alisa”. Whether the job offer or “Alisa” are genuine remains unknown.

AfD politician from Hamburg takes up allegations about arms trade

Either way, the false report about arms smuggling made its way to German politics: a German website called Weltexpress picked up the entire “research” of “Journalisten Freikorps” on September 14 without any further investigation or verification. The alarmist title of the article reads: “Military aid to Ukraine poses an imminent threat to the inhabitants of Europe.” “The facts uncovered once again pose the question whether continued military aid to Ukraine can still be justified by Germany and other European countries,” the website states.

This report was shared on Facebook by Hamburg AfD politician Olga Petersen on September 27: “Reports on arms smuggling through the ports of Bremerhaven are piling up and our beautiful city of Hamburg also finds mention in the reports,” she wrote. “In order to get to the bottom of this, I would like to submit a question to the Hamburg Senate.” Hamburg is not mentioned in the Weltexpress report; it remains unclear where Petersen found the supposed mention.

Since mid-July, the focus of the Russian operation has been on Germany

One thing is certain: since spring 2022, the Russian disinformation industry has been slowly warming up and is now pulling out all the stops. Meta reports that in the course of the operation, “mini-brands” were created to spread anti-Ukrainian content in different languages: Accounts with the same names (for example, “Freies Deutschland”) were created on different platforms. The goal: to build self-reinforcing echo chambers.

It is also clear that Germany increasingly became the center of attention. Meta’s analysis points out: At the beginning, several countries were similarly affected by the fake news sites. However, this has changed. Since mid-July, at least 40 more websites have been created that imitate German news sites – no new ones have been discovered in other countries since then, according to Meta. Since Meta began blocking the identified websites on Facebook, the process of creating new ones has accelerated again, the report says.

It seems there is no end in sight to the Russian disinformation operation. It is impossible to quantify how big its influence on public opinion is. However, Hamburg police confirmed to us that AfD politician Olga Petersen has submitted her request to the Senate. The campaign has thus already made it into German politics.

Edited by: Matthias Bau, Sophie Timmermann

Most important public sources for this research:

- Analysis by Mandiant: „Hacktivist personas back latest GhostWriter disinfo op targeting Poland, Ukraine“, June 30, 2022, Cyberscoop: Link

- Article by T-Online: „Putins Troll-Armee greift Deutschland an“, August 30, 2022: Link

- Analysis by DFR Lab: „Russia-aligned hacktivists stir up anti-Ukrainian sentiments in Poland“, September 9, 2022, Medium: Link

- Report by Meta: „Taking down coordinated inauthentic behavior from Russia and China“, September 27, 2022: Link

This article was first published in German on September 30, 2022. You can access the German version here.