Energy crisis

How Russia enlisted German politicians, business leaders and lawyers to ensure German dependence on Russian gas.

They really let their hair down: white rabbits, dirndls and Stalin doubles all made appearances during the festivities. Sponsored by a host of companies from Gazprom to Porsche, a new generation of German-Russian business lobbyists celebrated. But what no one seemed to want to notice at the party: these “German-Russian Young Leaders” get-togethers mainly served the interests of the gas industry. Even Olaf Scholz let himself get roped in.

An investigation in cooperation with Policy Network Analytics

April 20, 2023

When Franziska travelled to the “Young Leaders Conference” in Sochi in 2017, she was looking forward to international discussions. But things didn’t quite turn out how she’d imagined. What the young lawyer remembers most is a series of bizarre experiences: women and men in Bavarian dirndls posing next to men in Stalin costumes in the Russian Olympic Park in Sochi. How people sung the Russian national anthem, hands pressed to their hearts, on top of a mountain. And how, late at night, everyone was driven to a disco where “endless amounts of champagne and vodka” were drunk.

“It was the strangest experience of my life,” says Franziska, whose name we have changed. She contacted the editorial team after becoming aware of CORRECTIV and Policy Network Analytics’ investigation into the Gazprom lobby – as did other participants, all reporting similar things. Although they themselves want to remain anonymous, they want the (what they themselves call) “Russian propaganda” to be made crystal clear.

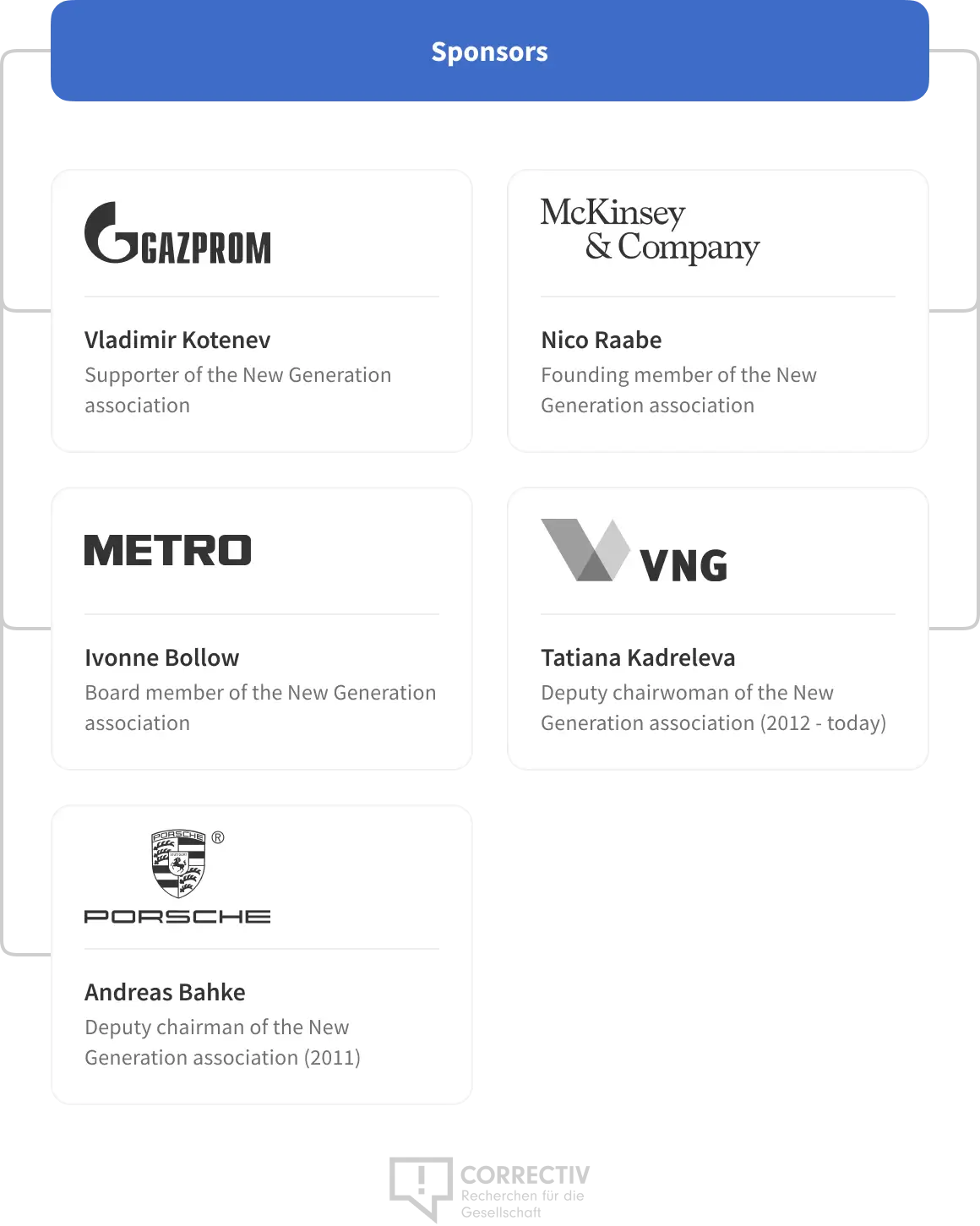

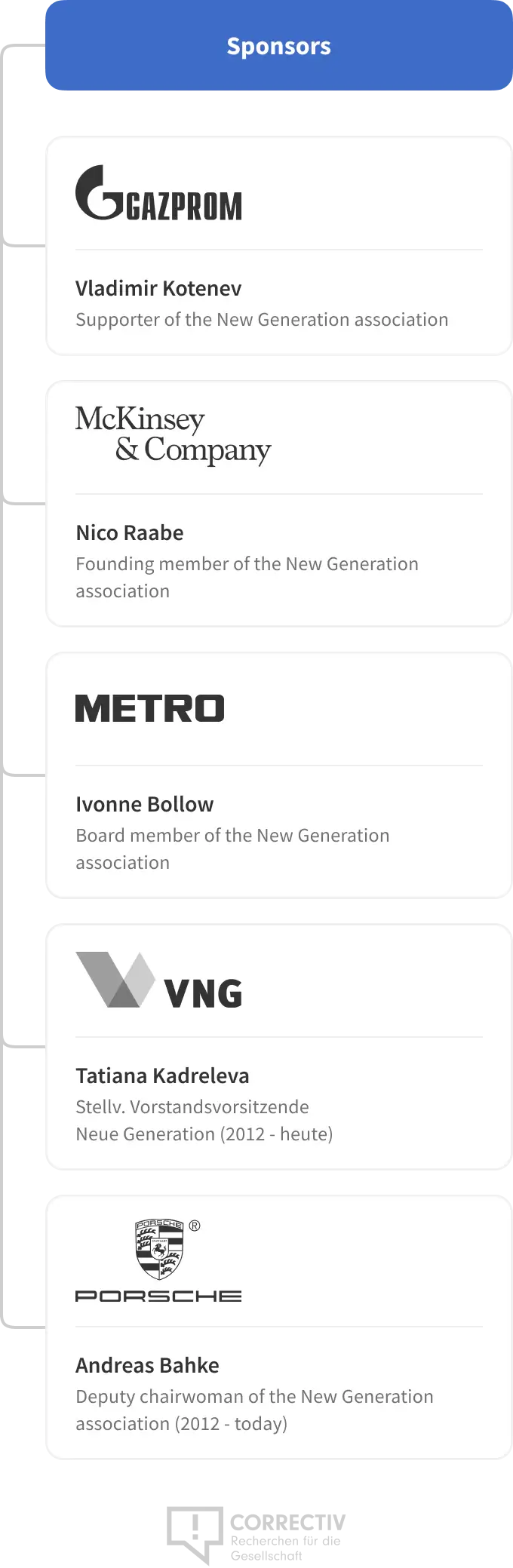

The “German-Russian Young Leaders” conferences saw business elite and high-profile politicians sharing the same stage. Every year, more than 200 talented young people from German and Russian companies met at lavish parties: the children of well-known German business families and the nobility; companies such as Gazprom and Metro sponsored their younger members of staff’s days of extravagance and excess. McKinsey sent dozens of employees to the parties; the Russian ambassador invited them to his villa in Berlin; Olaf Scholz, then mayor of Hamburg, invited them to his banqueting hall. Even the Russian secret service is said to have been among the guests.

Those who attended felt part of a young German-Russian elite; it was the next generation of lobbyists counting on German-Russian business. For many years, there were only winners here: corporations networked for current and future employees. The participants revelled in luxury. Russia’s growing influence on the German energy market went unchallenged, and the “Crimea crisis” did nothing to change the conference. Everything went on like clockwork.

By 2022, Germany was dependent on Gazprom and Russian oil. When Russia started the war against Ukraine, the German government had to spend hundreds of billions of euros to ensure that heating would remain more or less affordable.

No one wanted to admit that leaving the party was long overdue. Not even after the annexation of Crimea in 2014. Today, many of those involved with these parties want to play down or conceal their participation: no one wants to be reminded of who once paid for these lavish events. The sponsors will not disclose how much they spent, and host cities and organisers contradict each other.

These extravagant gatherings show how Germany became dependent on Russia thanks to a mixture of naivety and hubris. CORRECTIV talked to event participants and organisers and, in cooperation with the research initiative Policy Network Analytics, gathered background information on the dense network behind the events, its sponsors and the organisation that founded the conferences.

Franziska ended up in Sochi thanks to a friend. A committed member of the FDP, the German liberal party, recommended her to the organisers and thus ensured her an invitation to the event. The circle is elite, everyone knows each other, and they recommend each other. “Superficially, it was about exchange between young people, who, by the way, were often much older than 30. In reality, however, it was a very shady lobbying event – for the Russian government, for Gazprom,” says Franziska today.

Everything was pompous and extravagant: at the first reception in the evening, vodka and champagne flowed, the tables groaned under the weight of the food, whole animals – suckling pig, salmon and lobster – were served, and everything was in excess – the guests could only eat a fraction of everything on offer. There were workshops on only one of the three days. Everything else was a “luxury binge”. But the organisation left nothing to chance: the seating arrangements were fixed, the rooms in the luxurious 5-star hotel with a view of the Black Sea were pre-assigned – a German man would always share a room with a Russian man, and a German woman with a Russian woman, a tradition stemming from Russian youth groups. Even the exact dress code was prescribed. When Franziska appeared in a trouser suit instead of the stipulated evening gown, someone whispered to her that she was “very brave”.

Conversely, Franziska found the speeches and workshops not very brave at all. There was no space for criticism of the country that had annexed Crimea three years earlier – and would then invade Ukraine just a few years later. From Franziska’s point of view, “Nobody was really interested in political exchange there.” This is also confirmed by Ludwig Fenn, whose name we have also changed, and who attended the conference a few years earlier in 2013 in St. Petersburg. There was hardly any exchange with Russian participants. It was obvious that this was a gathering in which a self-proclaimed elite met to party and network. And, incidentally, to put everyone in a good mood to do business with Russia.

Guests like Franziska were the exception. In 2016, for example, out of 200 participants only five were explicitly listed as students; in 2013, the number was similarly low.

The conferences, which sometimes took place in Russia, sometimes in Germany, were organised by the German association “Deutschland-Russland – die Neue Generation” (“Germany-Russia – the New Generation”). From the very beginning, the association brought in representatives of energy companies, and gathered supporters from the likes of the circles surrounding former chancellor Schröder and Russian company Gazprom, to contacts close to the Kremlin itself. The political foundations of the German conservative party CDU and liberal party FDP were also supporters. Gazprom and McKinsey were conspicuously close. But the association still tells a different story to the outside world.

A brief look into the history of the association is worthwhile.

In 2010, the children of well-connected businessmen and ambassadors met in a Berlin pizzeria. Their professed goal: to promote international understanding between Russia and Germany through an association. It would enable young people to meet each other. One of them was Nico Raabe, the then 31-year-old project manager at McKinsey, one of the largest management consultancies in the world, a man well connected in Berlin circles. Today he is still an expert on the gas industry at McKinsey.

Also at the pizzeria were then 24-year-old Christoph Herzog von Oldenburg and 22-year-old Anne-Marie Großmann. Von Oldenburg comes from an aristocratic family with many connections to Russia, and he would later become the face of the “Young Leaders” conferences. Großmann is the daughter of Jürgen Großmann, the former boss of the German power company RWE. The association was registered in her name. Today she is a managing director at the Georgsmarienhütte steel company, which her father, a friend and skat-playing chum of Gerhard Schröder, once chaired.

The case of Vladimir Kotenev is also remarkable. The then 28-year-old son of the former Russian ambassador was also one of the association’s founding members. The association was supported by the Russian state envoy, as stated in a letter from the association’s lawyer obtained by CORRECTIV.

Von Oldenburg and Raabe had at times had a very close relationship with Kotenev Senior, the Russian ambassador in Berlin at the time. His wife was on the board of trustees of the conference. Kotenev Senior also played an important role at the conference, according to participants’ observations. Some of the first meetings in 2009 and 2010 took place at the Russian Embassy in Berlin. The 2010 programme also included a meeting with former Chancellor Gerhard Schröder.

When the ambassador took up a position at Gazprom in 2010, he helped Gazprom co-sponsor the conference the following year. However, the association later fell out with Kotenev, Oldenburg, the association’s founder, told CORRECTIV. Gazprom and McKinsey forged close ties during the same period. But more on that later.

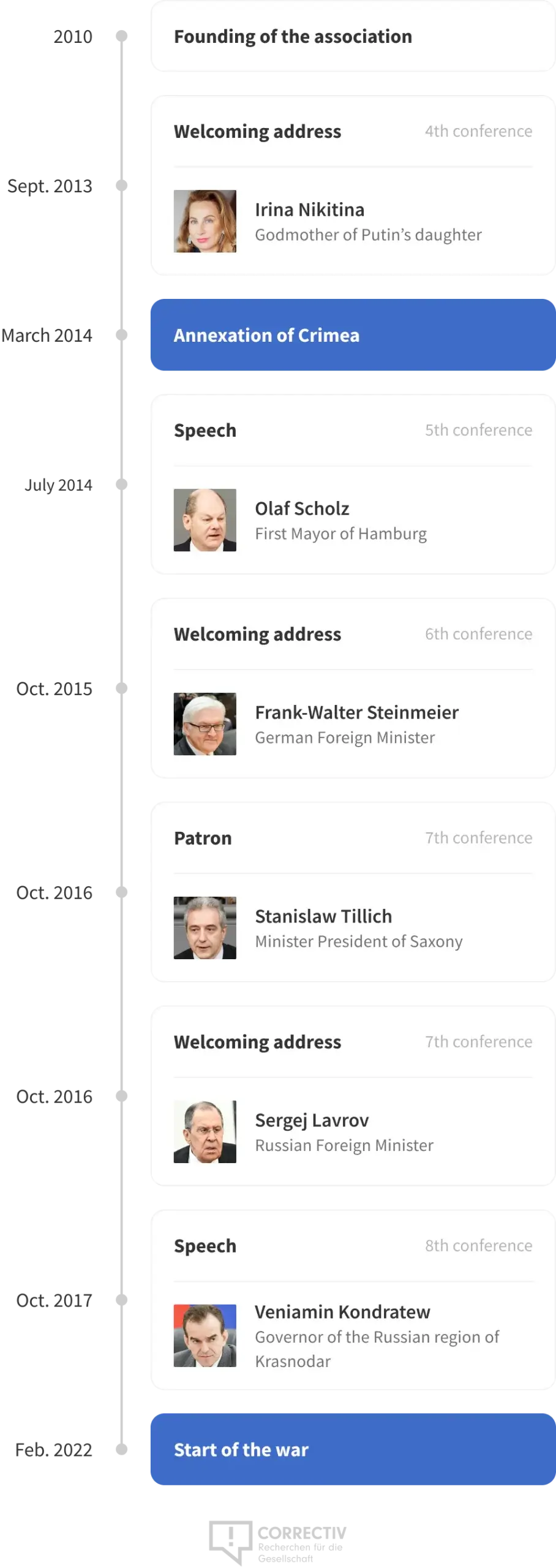

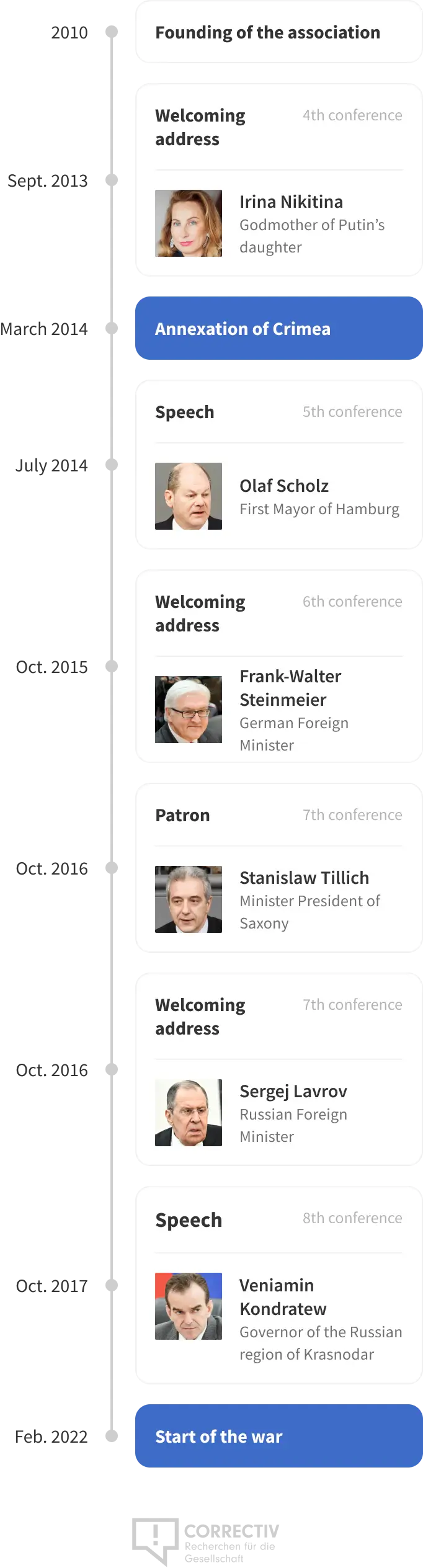

The association apparently sought proximity to Russia’s centre of power. One of the women who sat on the board of trustees is, according to an FAZ investigation into the association, the godmother of Vladimir Putin’s first daughter.

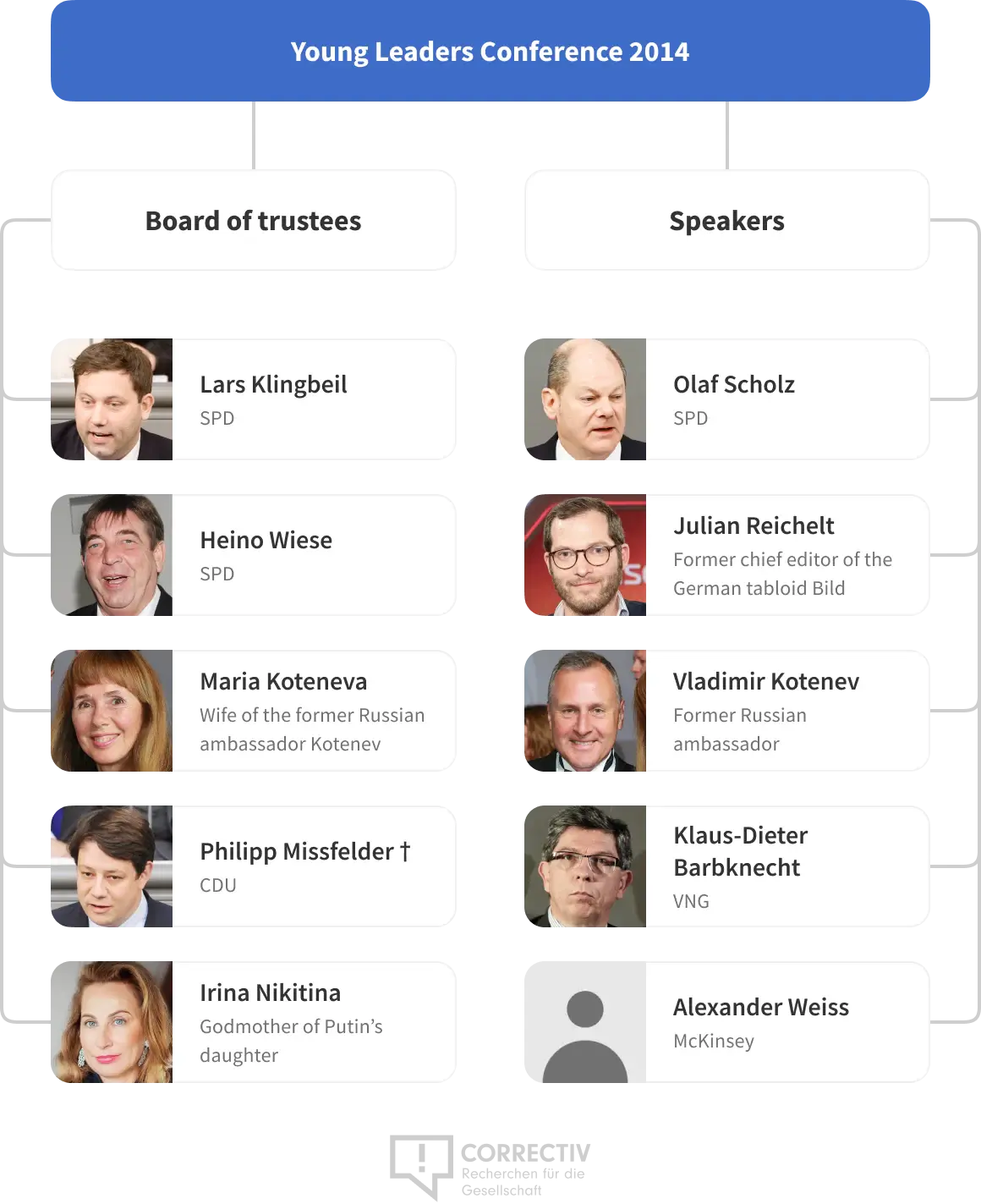

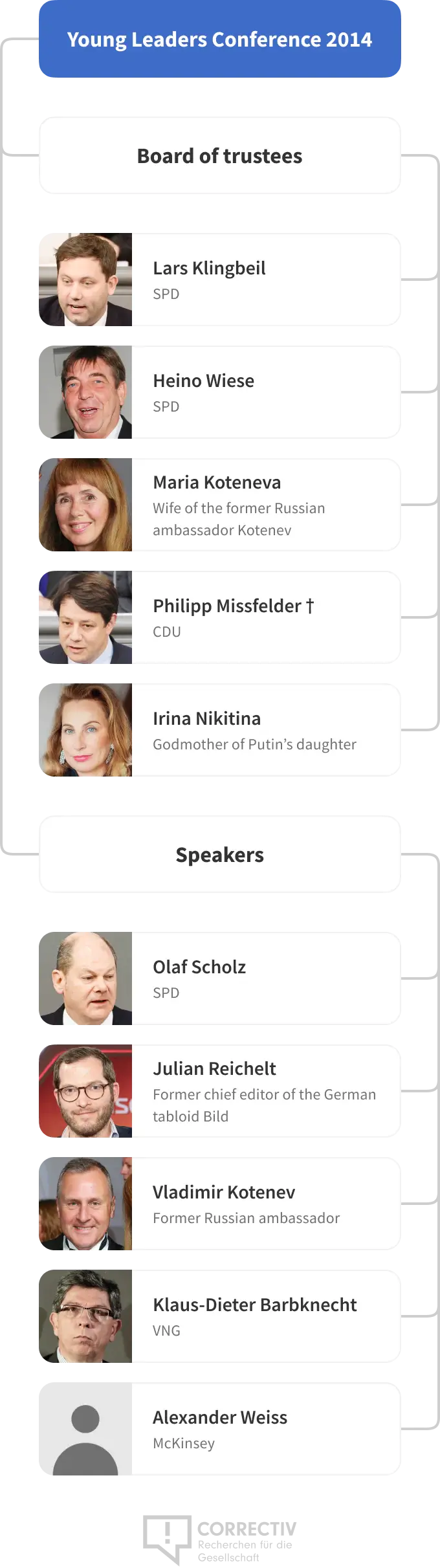

German politicians were also willing to get involved: prime ministers of the conservative CDU, the Bavarian counterpart CSU and the democratic SPD regularly gave the welcoming address. Stanislaw Tillich, former CDU Minister President of Saxony, became a patron of one of the conferences. Former office worker for Schröder and now the current SPD party leader Lars Klingbeil was on the conference’s board of trustees, as was Heino Wiese, one of the key figures for the SPD’s contacts with Russia. The FDP and CDU also supported the “Young Leaders Conferences” through the party-affiliated foundations Friedrich Naumann for the liberal party and Konrad Adenauer for the conservative party. Even after the annexation of Crimea in 2014, the Adenauer Foundation did not withdraw its support. The Naumann Foundation did briefly suspend its involvement in 2014, but returned as a supporter in 2015. Today, no one wants to be self-critical. The annexation of Crimea in 2014 changed the “political framework”, writes a spokesperson for the Adenauer Foundation. However, civil society contacts and corresponding formats have remained unchanged.

Good business with Russia, change through trade: that was the German position, which shocked many other European countries. Especially when it came to energy: the Nordstream pipeline was planned, which would allow ever increasing amounts of climate-damaging gas to flow from Russia. There was hardly any criticism of it in Germany. Yet 2014 could have been a turning point.

As the world held its breath and started to sanction Russia for occupying Crimea, the conference planning carried on as normal. Three months after the invasion, the “Young Leaders” met in Hamburg, under the patronage of Olaf Scholz. At that time, he was still the first mayor (SPD) of the Hanseatic city, today he is the Chancellor of Germany. He gave his welcome speech on the museum ship San Diego, and the next day he again welcomed his guests onto the Elbe. He praised German-Russian relations. There was, he said, no room in the medium nor long term for alienation and thinking in terms of spheres of interest – and that also applied “when the circumstances are more complicated and political differences come to light”.

In his speech, Scholz identified “hopeful signs” for a rapprochement between Ukraine and Russia, even though he stressed that the “sovereign integrity” of a country couldn’t be called into question. This was precisely the tone of the event: especially after the Crimean annexation, trust must be “rebuilt all the more”, as Oldenburg, the association’s chairman, wrote. However, the annexation is not mentioned once in the final 31-page report of the conference. Neither the Federal Chancellery, the SPD, nor Olaf Scholz’s constituency office would comment on the appearances when asked. Scholz’s friend and colleague Lars Klingbeil, one of the two federal leaders of the SPD, is more self-critical. “Close economic cooperation with Russia had cross-party consensus in Germany for many years. Seen from today’s perspective, it was a mistake.”

One participant, who was also involved in the organisation of the conference, reports that some workshops in 2014 were political. There had already been some unrest behind closed doors on the subject of Crimea. She thought the association’s commitment to exchange was good. But she was also amazed at the matter-of-factness with which a Russian member of the Duma, talking to a member of the European Parliament, was able to spout propaganda in Hamburg at the time. It was “harrowing”, even if there was also open opposition to it at the time.

The conferences’ tenor was always the same: cooperation had to be expanded – and criticism had to be quietened. In a report on a discussion on the “role of art in the state”, in which former chairman Julian Reichelt of the tabloid newspaper BILD took part, we find a shocking claim: it can be fruitful to suppress artists. “A hungry artist is the best artist, they work differently.” The report summarises the reaction to this as follows: “This statement sparked a controversial debate, leading to the conclusion that the positive effects of oppression depend on its extent and the general circumstances.”

In the years after 2014, high-profile Russian celebrities also supported the conference. Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, the same one who today explains to the world why Russia had to invade Ukraine, gave a welcoming speech in 2015 and 2016. He called the time a “turbulent situation in world affairs”.

Participating in 2017, Franziska also remembers a “blatantly nationalistic” speech by Veniamin Kondratev, the governor of the event’s hosting region of Krasnodar. In it, he defended the otherwise barely mentioned occupation of Crimea and described it as a necessary reaction by Russia. This caused some unrest in the audience – but the event went on unaffected.

Today, no one wants to give precise information about the sponsorships of the conferences. But extravagant celebrations cost money, a lot of money. Oldenburg, the association’s chairman, told CORRECTIV that the host cities in Germany – Hamburg, Munich and Dresden – would have paid for the reception, for example, with luxurious appetisers, an abundance of expensive fish and meat dishes, champagne and vodka on tap. But the city of Munich says there is no evidence of their sponsorship of the event, the Hamburg Senate, when asked, can at best recall costs for the “reception and technology” of around 10,000 euros. Dresden did not respond to our inquiries. Oldenburg then writes that the correspondence with the cities was “unfortunately not preserved” and that there was no central organising office. But he reiterated that: “From 2011 onwards, one evening at each conference was usually hosted by the host region or city.”

CORRECTIV and Policy Networks Analytics have the lists of companies that supported or sponsored the conferences: Porsche claims to have provided a luxury shuttle service and moderate financial support from 2012 to 2015 in order to “foster relations between emerging labour and business leaders from Russia and Germany.” VNG, Siemens, Gazprom, E.ON, McKinsey and Metro also participated. According to Oldenburg, chairman of the association, direct economic interests played only a very minor role at the conferences. It is therefore interesting that some of the companies on the sponsor lists of the “Young Leaders” were those who found it particularly difficult to say goodbye to business with Russia after the outbreak of the war.

The networking of the young employees also had a long-term effect. At the conferences, the “young leaders” partied together and later found each other on digital alumni platforms. Some of them have gone on to have stellar careers in the corporations that appear in the sponsor lists.

In the “Young Leaders” alumni group, the participants arranged further meetings. The “German-Russian sailing adventure” for example, or the “ski challenge” at the exclusive Kitzbühel ski resort. “As in previous years, we will stay in luxury apartments,” the organisers wrote in a Facebook group. A meeting with representatives of a “large Chinese investment fund” was also scheduled. Luxury fun and business dealings seem to have always been close bedfellows for the “Young Leaders”. Among the participants are representatives of five-star hotels, of the so-called Erben-Zentrum, a consulting firm for wealthy heirs, as well as of investment consultancies, Goldman Sachs, Rheinmetall and market-liberal think tanks such as the Prometheus Institute, whose founder identifies as a climate change denier.

Alexander von Bismarck, who founded the Circle of Friends of the New Generation and is part of the conference’s inner circle, recently proffered a particularly bizarre act of friendship towards Russia. He decorated a tank with 2000 roses in Berlin. The tank had actually been placed in front of the Russian embassy in protest against the Putin regime. Bismarck’s great-nephew said that he wanted to call on the German government to finally negotiate peace.

And it seems to pay off to stay in the alumni network: some of the association members of the “New Generation” are now in high-ranking positions in the “Young Leaders” sponsor groups. Faces from the board of the “New Generation” can now also be found at Metro AG in Düsseldorf and at the VNG Group in Leipzig, for example. Both Metro AG and VNG are still active in Russia today.

And then, of course, there is the gas industry. The Russian energy company Gazprom also appeared as a sponsor of the “Young Leaders” conferences and sent speakers and workshop panellists to events. The sponsors had “no influence whatsoever on the content of the conferences”, the association’s board told CORRECTIV. The network of participants includes at least 28 representatives from Gazprom. They celebrated there together with the employees of a number of German corporations that had sealed profitable contracts with Gazprom during the same period.

Or the consulting firm McKinsey, for example, which sponsored the “Young Leaders” from 2009 to 2012. Over the years, at least 28 representatives of the corporation took part in the conferences. Among them was the co-founder of the association, Nico Raabe. “Everyone knew Nico,” says Franziska, who was there in Sochi in 2017.

According to information from Business Insider, McKinsey was in business with Gazprom from 2010. As maintained by the report, the consulting firm received 50 million euros to organise events, talks and publications for Gazprom in order to make Russian gas “indispensable to German industry”. The head of McKinsey’s German office, Frank Mattern – later also on the board of trustees of the “Young Leaders” – was in talks about the deal with Gazprom Germania head Vladimir Kotenev, the former Russian ambassador. He was also a supporter of the “Young Leaders”, at least in the early years. Mattern wrote a letter to Kotenev during this time. It said: “We would very much like to seize the opportunity to effectively support Gazprom Germania and you personally.”

Then there’s the Leipzig-based energy company VNG. It sponsored the “Young Leaders” conferences from 2012 to 2015. VNG was dependent on state aid after the gas freeze from Russia because its business strategy was strongly oriented towards Russia. In its investigation on the Gazprom lobby , CORRECTIV and Policy Networks Analytics showed that VNG was linked to several pro-Russian lobby organisations in recent years.

Initially, it was a relatively contained circle of managers in associations (which often had similar names to each other), and which continuously deepened business relations, especially in the energy market. That was up until Germany became completely dependent on Russian gas. A quick reminder: in addition to the construction of the Nordstream 2 pipeline, Gazprom was also awarded the contract for Germany’s gas storage facilities in 2015, which was secured by the German government with a billion-euro guarantee.

The German-Russian Forum is one of the associations that is also important in the sphere of gas lobbying. It is here that some old “Young Leaders” acquaintances meet again. McKinsey partner Nico Raabe was on the board of trustees, and several other board members as well as the chairman Oldenburg are members. For a long time Vladimir Yakunin represented the group’s proximity to the Kremlin. An enigmatic figure, Yakunin’s sphere of influence stretched from Moscow to Berlin: he used to be a close friend of Putin’s, worked for the KGB and was a former railway minister in Russia. The oligarch is on the US sanctions list and ran an association in Berlin, the “Dialogue of Civilisations”, which attracted attention mainly for its pro-Kremlin lobbying. The “New Generation” association also sought contact with Yakunin at times: Oldenburg invited Yakunin and the association to a classical concert in the Berlin Philharmonie in 2014. But Oldenburg has not met with Yakunin “for years”, he told CORRECTIV.

Critics of Russia did not have much room at the party. Oldenburg named just a handful of opposition figures who were part of the conferences to CORRECTIV. He stresses that the conferences were about cultural and political exchange. According to Oldenburg, there were also undercover agents from the Russian security services among the participants – although he has no proof of this. That is why it was dangerous for members of the opposition to speak out. Daniil Bisslinger, a Russian who was later suspected of espionage, was at the conference in 2016. The fact that the party of young elites was also filled with informers apparently did not bother the organisers.

The programme of the conference in Sochi 2017 included a trip to the Olympic Park. Franziska remembers that a participant asked the stadium guide in Sochi whether people had actually been forcibly resettled for the Olympic construction project. The man just laughed the question off. “Nobody was seriously interested in an exchange,” says Franziska. She had already participated in various youth events, such as summer schools for European law students or green university groups. “There was real discussion there, struggling for answers – at the ‘Young Leaders’ meetings, the answer was clear: Russia is great.”

The young lawyer will not forget the events in Sochi for the rest of her life. In the Olympic Park, she says, white rabbits were hopping around. Magicians passed by the sumptuous coffee table where she was sat. Franziska, like everyone else that day, wore traditional Bavarian dress, just as the invitation had stipulated. In the stadium itself, she remembers, Stalin doubles stood to have their picture taken with the participants in lederhosen and dirndl. Later, they took the cable car up into the mountains; at the top, national anthems were sung, the Russian, the German, the Bavarian, everyone standing with their hands on their hearts. When Franziska remained seated, an older man she didn’t know with a name tag from the association approached her and said she was being disrespectful and should stand up. Oldenburg says today that he knew nothing about the Stalin doubles.

One day after the outbreak of the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine, on 25 February 2022, Oldenburg wrote a letter to the circle of former conference participants. The letter was made available to CORRECTIV. In it, Oldenburg says how disappointed he was in the Russian leadership and condemned what Putin had set in motion. However, he wrote of Russia’s “military operation” at a time when the West was unanimously talking about a “war” against Ukraine. “Military operation” has always been Putin’s choice of words. It was an oversight, Oldenburg claimed when asked by CORRECTIV, saying he would no longer phrase it that way today. He had condemned the war from the very beginning and made that clear in the letter. In “no way” had he “adopted the Russian narrative.”

His distancing comes rather late: the “New Generation” network was practically lubricating oil for the close ties to the autocratically ruled Russia. And the big party where it all happened was apparently too intoxicating for the Germans to notice who was instrumentalising whom.

Translation: Ella Norman

This investigation into the German-Russian network is dynamic. We started by looking into the Gazprom lobby. We are constantly adding to our findings, not only to document who was involved, but also to publicly show the structures of these lobbying networks. There is hardly any other area in which the influence on politics is now so obvious, and in no other area are the consequences of the decisions made at that time so serious as in the case of gas from Russia.

Support

investigative journalism

We are happy if you support our journalism with a donation. Help us finance CrowdNewsroom investigations like this story.

Unsere Reporterinnen und Reporter senden Ihnen Recherchen, die uns bewegen. Sie zeigen Ihnen, was Journalismus für unsere Gesellschaft leisten kann – regelmäßig oder immer dann, wenn es wichtig ist.