Every year fraudsters are robbing Europe’s citizens of 50 billion euros in tax money. A Europe-wide investigation by 63 journalists from 30 countries, coordinated by CORRECTIV.

The Story

Which version would you like to read?

- It is the largest ongoing tax fraud in Europe: criminal gangs are stealing €50 billion every year from EU members states, according to the EU commission.

- The losses are made worse by a lack of cooperation between EU members. Germany in particular is obstructing joint measures in fighting the tax fraud.

- Fraudsters are now eyeing the market for green power certificates.

- Islamist networks have used the fraud to finance terror.

- CORRECTIV has followed in the footsteps of one fraudster who played a major role in a high profile VAT fraud carousel. Our investigation reveals how this type of organized crime works and how governments in Europe struggle to combat it.

The story of Amir B. shows how a clever teenager rose from mobile phone trader to tax carousel lynchpin within just a few years. Following his tracks reveals the structure of the fraud system and the difficulties the authorities face in the war against VAT fraud.

Most people don’t realize why it’s so much cheaper to buy mobile phones on eBay rather than from the manufacturer direct. But not Amir Baha (name changed) who understood perfectly when as a 16-year-old schoolboy he started selling mobiles in a city in Germany’s North Rhine Westphalia. “All around the world people know: if you want to sell mobiles in Germany, they have to come from fraud. Otherwise there’s no money in it.” That’s how he summed it up nearly a decade later to prosecutors in Cologne.

Baha was a smart kid who rose to be a multi-millionaire in the space of a few short years. He was at home at Dubai’s nightclubs and flew first class. He traded mobile phones, game consoles, copper electrodes and even certificates for carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. At the time of his arrest, he was running eleven companies registered in other people’s names.

He did not, however, earn his money from mark-ups on these products but from the tax he stole. By moving his merchandise in circles across borders and without paying value-added tax (VAT), he siphoned off millions from state coffers, tricking the authorities into paying him and his partners money they weren’t owed. Opinions differ as to how much exactly. Insiders estimate €110 million, one prosecutor puts the number at €60 million, a court verdict against Baha at €40 million.

In any case, a huge amount for somebody who traded in mobile phones. An employee with an above-average salary of €5,000 per month would have to work 1,600 years to earn €100 million. In his crowd, however, Baha was only a medium-sized player.

This kind of crime, dubbed ‘VAT carousels’ or Missing Trader Intra-Community (MTIC) fraud, is costing Germany from €5 billion at the low end of estimates to anything up to €14 billion annually. As Europe’s largest economy, the losses are higher than elsewhere. But VAT fraud carousels are an EU-wide problem with the EU commission fixing the total annual tax loss at around €50 billion.

In October last year, CORRECTIV published its investigation into the highly complex share deals known as Cum-Ex, which are designed to ‘reclaim’ tax that was never in fact paid. The Cum-Ex operators require the assistance of teams of highly sophisticated lawyers and bankers to help engineer the trades. By contrast, VAT fraud, some reckon, is Cum-Ex for the masses.

Even teenagers such as Baha can advance from small-time mobile phone seller to multi-millionaire within a couple of years. For the public, the result is the same: billions of tax money ends up in criminals’ pockets rather than going into hospitals, schools and law enforcement.

“Why people would do any other form of criminality, I don’t know,” says Rod Stone, a former British tax investigator and one of Europe’s leading authorities on the subject. “Why do drugs, why do anything else when they can make so much money out of this?” Stone also questions why hardly any European countries are taking the problem seriously despite the enormous losses. VAT fraud is off the political agenda and rarely makes it into the headlines.

To shed light onto this under-reported issue, CORRECTIV created a European media team with journalists from each of the EU’s 28 member states plus Norway and Switzerland: 63 journalists from 30 countries shared documents and information and jointly investigated the question of why European governments appear helpless in the face of this cross-border VAT fraud. In some cases, it is alleged, the illicit proceeds have ended up not only with organized crime but also with Islamist terror groups, according to official documents.

Get on the list

We keep you in the loop on our investigations. Subscribe to our newsletter here for free.

Troubled

Start

By his own account, Baha has a troubled childhood. The second youngest of six children, he was just a few months old in 1990 when his mother fled their home in Afghanistan to live with a relative in Germany, escaping both the aftermath of the Soviet occupation and her violent alcoholic husband.

But the father came after them. Once he kidnapped Baha to put pressure on his mother. Another time, Baha’s skin was badly burnt when the husband threw a pot of boiling water at his wife. She didn’t want to involve neighbors or the police. Instead, she changed address several times. Baha attended primary schools in different cities.

Baha’s introduction to organized crime began with small, legal attempts to make money. Those who have met Baha regularly say he is charming and obliging, speaks five languages and has a knack for IT.

Initially, he set up a website that brought in small sums in advertising. He also started selling a few mobile phones each month on the side, to family members, at school and using eBay. Because he was only 16, he asked one of his older sisters to obtain a trading license on his behalf.

He had recently turned 18 years when he registered his first company. This time, he involved another older sister who was studying business administration. He told her it was just a matter of formalities. “I assured her everything would be okay. I meant to stay clean through the company,” he later told prosecutors. He was concerned that nobody would take him seriously as a company director because of his age.

Baha used this firm to buy mobile phones in bulk in Luxembourg and the Netherlands, making between €50,000 and €100,000. “Stupidly, I didn’t use the money to pay back debt but for setting up the company and expensive cars for the company,” Baha claimed, according to his arrest warrant.

The legal trade in pre-paid phones on eBay didn’t go well. “So I had to return to my normal ways,” Baha said. Normal being VAT fraud.

Criminals operate across borders. So can journalists.

CORRECTIV is the first non-profit investigative newsroom in the German-speaking region. We strengthen civil society and democracy through independent and investigative journalism.

Grand Theft Europe is a Europe-wide media investigation coordinated by CORRECTIV. We connect Europe with our investigations. Enable more such European investigations by donating to us.

Baha found business partners on online platforms. Every morning he chatted with them and found out which goods were being sold or which were in demand. His status was always “W2B”, or “waiting to buy.”

Baha put these slogans on his instagram account: “Nothing lasts forever – Except Family.” Baha shows off pictures of Emirates first-class flights, Dubai skyscrapers and fancy dinners in upmarket steak houses. He tags them #LaFamilia or #BrothersReunion. The family was his rock but would later prove to be his Achilles’ heel.

A FIRST RED FLAG

By 2007, investigators were on his case. A Cologne savings bank reported a money laundering red flag in relation to the teenager’s company. The bank thought it suspicious that his company was booking €1.7 million in revenues immediately after opening an account, part of it from outside Germany and most of it in cash.

The authorities then froze some of his company’s money and Baha found himself in trouble with the suppliers he bought mobile phone from. “I knew I wouldn’t be able to pay back the money legally. I’d already involved my sister and under no circumstances could my mother know all of this,” he told prosecutors.

One of his clients suggested Baha repay his debt using fraudulent invoices and offered money up-front. He dictated prices, and buyers and sellers. Three ‘businessmen’ visited his sister, demanding their money back and threatening her. His sister “just kept crying. She didn’t have a clue,” Baha later told prosecutors.

Baha, now 19, was in debt, his sister was being threatened, and investigators were searching his flat and going through his company’s books. Following the money laundering report of the savings bank, he was on the radar of tax investigators in state capital Düsseldorf.

Yet Baha was unfazed. He decided to commit himself, later saying this was the moment he turned “really criminal”.

He went on a shopping expedition for merchandise in Luxembourg and the Netherlands. “I had to borrow money from the State,” he told prosecutors, using a German expression to refer to tax theft. “I actually did obtain goods from Luxembourg and Holland. Then sold them in Germany and didn’t report the VAT.”

A complex system

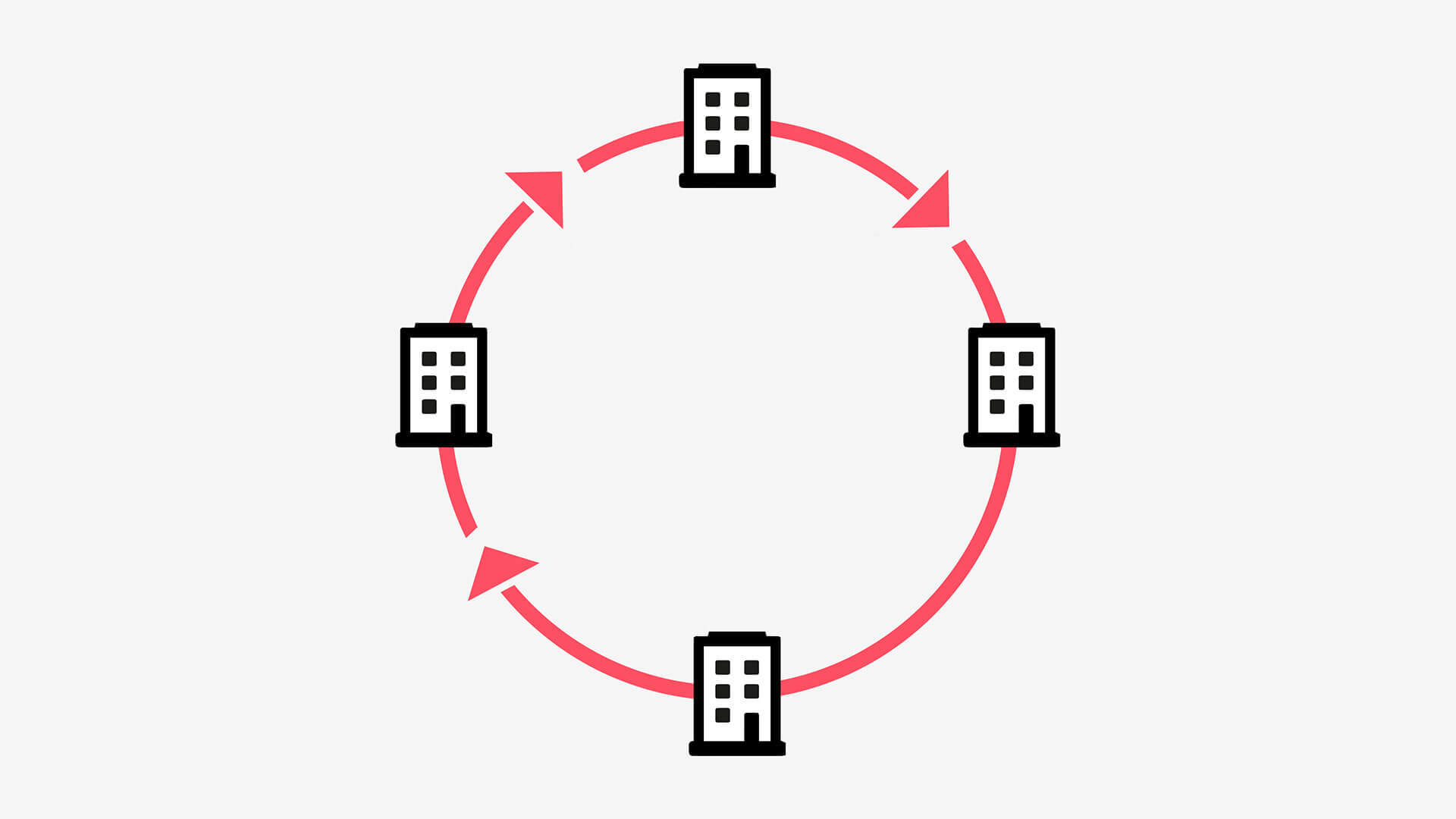

Here is an explanation of how VAT fraud carousels or MTICs work. The same goods are traded several times – in circles – using both real and fake companies. Tax authorities only take note when it is too late and the fraudulent companies have long disappeared.

VAT fraud is enabled by a complex system of tax settlements. Only the final transaction is supposed to be subject to VAT. That’s why legitimate traders invoice their buyers with VAT and pass on the tax, which in Germany is 19 percent in most cases, to the tax office. The traders each in turn ask the tax office to reimburse them for the so-called input tax they have paid when buying their own supplies.

There is a basic flaw. The tax office pays out the rebates without further ado or checks. At the same time, the system assumes that the traders will also pay the due taxes to the state within 90 days.

The European VAT system, introduced with the advent of the European Single Market on 1 January 1993, allows for the really lucrative fraud. Its basic idea: goods and services are taxed at different tax rates across EU member states but can be freely traded across borders.

If a trader in Germany buys goods in France there is no VAT due. If the trader sells the product onto another trader in Germany, he adds 19 percent VAT to his price, as do all further buyers.

But under the fraud, the trader who bought in France does not report any sales nor does he pay VAT to the tax office. The tax office will notice this so-called ‘missing trader’ only many months later. This trader often exists only on paper, in the shape of a letter box and often using a homeless individual as frontman. Or a relative, as in the case of Baha.

The last trader in the chain who sells the goods into to another EU member state is called the ‘distributor’. In a genuine commercial chain, he is eligible to have the VAT paid in Germany reimbursed. But in a fraudulent scheme, any number of middlemen will act as ‘buffers’ between the missing trader and the distributor, making the scheme larger and more difficult to detect. They also act to delay the exposure of the fraud.

Companies controlled by Baha were used as such ‘buffers’. Neither the buffer nor the ‘missing trader’ need to have their own bank account as much of the trade is flowing through online trading platforms. “Profits are somehow calculated at the end and distributed,” Baha said. His companies were used by several sponsors, sometimes in parallel, sometimes in sequence.

It’s like passing ‘Go’ on the board game Monopoly. Every time goods enter the country, there’s money flowing in. The VAT fraudsters just need to make sure they ‘pass Go’ as often and as quickly as they can.

There are several VAT fraud variants. Some involve non-EU member states, others physical goods such as expensive cars which actually cross borders. Sometimes it’s just on paper, something in which Baha also specialized. More on this later.

In principle, any item on which VAT is payable can be used but in practice, goods that are expensive and take up little space work best, allowing traders to avoid high transport and storage costs.

At home in the digital age

“It started with foodstuffs such as onions and potatoes,” says Pedro Seixas Felicio, head of the white-collar crime division at Europol. “Then metals, mobile phones and computer chips, later cars. Finally, virtual goods such as pre-paid phone credits and carbon dioxide emission certificates became really popular.” Felicio has been coordinating EU-wide police operations against VAT fraud for four years.

VAT criminals feel right at home in the digital age. When investigators were still trying to unearth VAT fraud using retail goods and luxury cars, people such as Baha had already moved into more exotic trades involving CO2 emission certificates. This one landed Germany with€800 million of losses in a 12-month period in 2009-10 alone, and other EU member states with an estimated €7 billion losses in total.

The emission certificates were designed to manage climate-harming industrial emissions following the 1992 Kyoto Protocol. But they were also perfect for fraudsters because they were digital and could be traded at high speed.

“Ninety percent of the carbon trade in Europe was fraudulent,” says Stone, the former UK tax investigator. He says that the fraud moves like the waves of the oceans, flowing back and forth between different products and countries.

When Baha caught one of these waves, his business expanded dramatically.

He was still 19 when he first heard about emission certificates. He was attending the huge IT tradeshow Cebit in the German city of Hanover where he had his own stand with a new company. This time, he’d registered the company in the name of a cousin who was honoured that Baha trusted them.

During the tradeshow, Baha happened to meet an Indian businessman calling himself Adam Hicks. A few months later, when they met again in the lobby of a Dubai hotel, ‘Hicks’ would convince Baha to enter the emission certificates scam.

“They were talking about a lot of money, really a lot of money,” Baha remembered later. “That really intrigued me.” Baha’s company was meant to act as a ‘buffer’, a middleman which made the network more difficult to penetrate. And he would contract with customers such as… Deutsche Bank. “The less I knew the better,” Baha said. On advice from Hicks, Baha also set up an account to trade emission certificates on the EU emissions trading system (ETS).

But even as Baha was preparing to enter the emissions racket, every single EU member state was already aware of the issues, says Stone. It was discussed both at Europol and Eurofisc, a European-wide body of tax experts where Stone represented the UK. All member states knew of the new VAT fraud scheme by July 2009 at the latest, Stone says. “After that, it was up to individual member states to stop it.”

A Crime Wave

In Britain, the authorities could see it coming as registrations for emissions trading spiked dramatically, especially from companies that had previously been involved in fraudulent mobile phone trades. The authorities realized that British firms were selling certificates to a France-based trader on a large scale. They warned their French counterparts.

They could only act when the fraudsters were already striking. There is actually a pretty simple tool against VAT fraud. It’s called ‘reverse charge’, which reverses the tax burden. Under this mechanism/provision, only the final buyer pays VAT. Trade between companies along the chain is not taxed and so there are no longer any rebates payable.

The EU needs to approve the application of reverse charge. When it granted approval to France, the fraudsters simply moved to the UK. Even though authorities were prepared, the UK still lost £250 million (€290 million).

It was obvious that the emissions-based fraud would also move on from the UK at some point even though its next target was less clear. The German government at the time showed little interest. When the first reports reached the federal government from German states, the response was: “Come back when losses exceed €100 million.”

A storm was brewing, but the sea was still calm. The German government preferred to sit back and observe. As it turned out, Germany was the fraudsters’ next target.

SIN CITY

On 21 December, 2009, Baha flew from Dubai to Las Vegas with somebody Adam Hicks, the Dubai-based Indian ‘businessman’, had introduced him to. This mysterious individual was supposedly one of the masterminds of the emission certificates-based VAT fraud. While the plane was spewing carbon into the atmosphere, Mr X was speaking non-stop on his satellite phone. “He was in a good mood and said he had sold emission certificates during the flight like never before. Several millions,” Baha told prosecutors.

The two spent a relaxing few days in Las Vegas, burning through between €100,000 and €200,000 a day on a 900-square-foot suite at the five-star Wynn Casino and Resort with a butler, “24-hour limousine service and two female companions“. “We had a great time,” Baha recalled.

They didn’t talk much business. Only that Baha was to use yet another company he’d created, as a ‘buffer’. And he needn’t worry. He’d be well rewarded.

Baha realized only much later that his share of the scheme profits was a mere 0.1 percent, or so he claimed. He said that the ‘missing trader’ and the buffers rarely get more than 0.3 percent. The authorities disagree. One insider say that in the case of Baha, a cut of one percent, or ten times as much as he claims to have earned, is more realistic.

Baha now had different plans. “I wanted to start something new again. But something clean, this time. With my family. You can trust your family,” he said. He refers to the traditional mobile phone trade on eBay. Another jobless cousin living in Germany acted as his front.

Baha himself, however, had relocated to the United States and Dubai. Now 20, he feared that German tax investigators might obtain an arrest warrant against him. He started using cover names on his business trips to Europe, such as Kevin Ahmadi or even George Soros and Warren Buffet. As ridiculous as these pseudonyms might sound, when used in emails or chat messages they were extremely effective in masking his activities and making investigators’ lives more difficult.

VAT fraud based on emission certificates involved not only mobile phone traders such as Baha but also employees at the mighty Deutsche Bank. Forming part of the cross-border ‘trading’ chain, branches of Deutsche bought certificates at below market price from dubious firms and then sold them on to ‘traders’ in other EU member states. Deutsche then had the VAT ‘reimbursed’ by the German tax office.

“I’d been out visiting all the banks that had been involved and given them a full rundown on what had happened,” UK-tax expert Stone says, recalling a 2009 tour of banks.

But when Deutsche entered the trade on a large scale it paid no more attention to the fraud risks than the German government. After Stone’s visit, it merely halted the emissions trading at its London operations and transferred it to its Frankfurt headquarters.

Seven Frankfurt-based executives were put on trial in 2016. One of them was jailed for three years while the others received suspended sentences. Years later, in 2018, Deutsche paid back €220 million to the German state.

Once the wave hit, Germany finally applied to Brussels for the use of reverse charge, which came into effect only in July 2010. Other states such as the UK introduced reverse charge and applied for permission at the EU retrospectively.

Germany had allowed Baha and his confederates to plunder the German tax coffers for a full nine months when divine retribution struck.

Wrath of Odin

Frankfurt prosecutors had named their Operation Odin after the ancient German god of war. They gathered 4,355 binders of evidence and wire-tapped 12,000 phone calls by the time 1,500 officers raided 500 companies across six jurisdictions: Denmark, the United Kingdom, Cyprus, Dubai, Hong Kong, and Germany on 28 April, 2010.

Meanwhile, other investigators had wire-tapped Baha’s phonecalls. Although he was one of 200 suspects and his name was on one of 14 arrest warrants, his residence in Dubai and the US seemingly put beyond the reach of German prosecutors.

But when his older sister was arrested, Baha contacted prosecutors in Cologne through a lawyer. He then sought to exonerate his sister via Skype and put down€450,000 for her bail. Prosecutors were interested less in Baha and his sister than in the masterminds behind the fraud. But talking about the masterminds was dangerous.

Baha refused to enter into a witness protection programme: it covered only two relatives but his family is much larger. He agreed to make an anonymous statement, but communication with prosecutors was difficult. His ‘superiors’ had allocated him a minder, he said. Baha could use Skype only when the minder was asleep.

Prosecutors learnt from Baha that the fraudsters had switched to the power and gas, and copper markets, now that the fraud using CO2 certificates had been stopped. He said that the fraudsters’ daily turnover on the power and gas market was €20 million, resulting in €3.2 million of tax ‘rebates’.

Europe:

a hamstrung response

“We’re talking about top criminals,” says Pedro Felicio of Europol. “They’re known. Most law enforcement agencies in Europe know who they are.” But they’re out of reach in tax havens like Dubai which show little interest in where their residents’ funds come from. And they don’t extradite to other countries.

The lack of political will in most EU member states also makes life hard for VAT fraud investigators. Inter-agency rivalry between law enforcement bodies and mistrust between member states outweigh the multi-billion losses, it appears.

Heinz Zourek has witnessed this first hand. Until 2015, the Austrian national was the EU’s top-ranking tax official. His failure to introduce a European-wide VAT form, he says, is his biggest regret from his time in office. “I was naive to think that would be possible.” He proposed 20 entry fields. Member states had other ideas, their proposals ranged from nine to up to 140 entry fields. Germany ruled out any changes to its own form altogether.

Member states’ tax offices are deeply mistrustful of each other, says Zourek. “The system is working well from one’s own perspective so any attempt at interference from outside is seen as an irritation.”

That’s why most experts think a proposed solution drafted in Brussels is already dead in the water. Under the so-called ‘final VAT system’, trade between member states would be taxed. VAT would only be levied in the country where the final transaction in the chain occurs.

It sounds simple but there’s at least one catch. When a German company sells a product in Bulgaria, the Bulgarian state would have to pass on the VAT to Germany. “Apparently German authorities prefer not to levy tax rather than trust their Bulgarian counterparts,” says Zourek. German states protested vigorously when the proposal was made in 2018.

The Czech Republic is a big victim of VAT fraud carousels and about the only EU member state that has put combatting the fraud on its political agenda. It has convinced Brussels to allow it levy all VAT using the reverse charge mechanism from 2020. But experts fear the fraudsters will simply adapt. When a study group set up by two German states looked at the reverse charge method, it concluded it would reduce but not eliminate the fraud.

Rod Stone, the British expert, says that only a standard VAT rate across the entire EU would completely solve the problem. In effect, the EU would have to be a federal state with harmonized tax legislation where Brussels levied all tax and distributed it across Europe. It is a vision that is not exactly popular with the European member states’ electorates.

The United Kingdom has shown, however, that it is possible to greatly curtail the fraud at national level, from £3.5 billion (€4 billion) before 2006 to around £500 million just three years later.

“Working in real time and creating a hostile environment are two things that work, from my experience,” says Stone, a conclusion he came to after 40 years as a tax investigator.

This strategy includes legislation that permits tax investigators to inspect offices of suspicious companies at any time day or night; immediate criminal prosecution in promising cases; asset freezing; and heavy punishments. Organized tax fraud in the UK is punishable with life-sentences.

Germany:

uniquely vulnerable

By comparison, Europe’s largest economy Germany is not up to speed. Three things ensure that VAT fraud is booming: the federal structure of the German state, tax secrecy and a lack of political interest.

Germany’s 16 states are responsible for levying VAT and investigating tax fraudsters. But neither prosecutors nor tax offices coordinate across state boundaries. Nor can German states directly ask counterparts in other EU member states for information. They have to go through the federal government and data protection officers of multiple agencies, which can take months.

The EU would like to accelerate criminal prosecutions but Germany is applying the brakes. EU member states are already exchanging information using Eurofisc, the network of national tax officials set up to combat fraud. Eurofisc recently introduced analysis of cross-border fraud networks.

But Germany is the only member state that opted to limit its participation in Eurofisc to observer status believing that joint data analysis would impinge on its tax secrecy regime, considered sacrosanct in Germany. Effective law enforcement will take more than joint data analysis. A new EU prosecution agency is planned to start work but not until November 2020 at the earliest.

In Germany, the government also hesitates to take up the fight, with powerful economic and financial interests fearing a higher tax burden. Taxpayers are almost entirely unaware of the scale of the fraud. And the government appears to prefer it that way, releasing hardly any information on the subject.

VAT Cat

Baha, meanwhile, was doing well, apart from the investigations in distant Germany and the minder of his partners in crime left. He was now 25, living mostly in California, had married and was active in real estate with his aunt and cousin.

Baha broke off contact with prosecutors in Cologne in the summer of 2011, after six months of negotiations. But his file continued to thicken. In January 2014, the Bundeskriminalamt (BKA), Germany’s equivalent of the FBI, entered the fray and contacted the US authorities. Prosecutors in Cologne wrote a second, detailed arrest warrant that ran to 90 pages.

On 31 March, 2014, the German authorities received a tipoff. The US Department of Homeland Security sent a message to the BKA, saying that Baha had just boarded Emirates flight 255 at Dubai international airport’s Terminal 3. The 15-hour flight to San Francisco departed Dubai at 8.26am. US law enforcement would need an international arrest warrant issued by Germany to take him into custody.

With the plane in the air, German officials had just five hours to translate the warrant and file it with their US counterparts. Tight, but they made it. Just when Baha presented himself at passport control in San Francisco, he was immediately arrested.

Baha was transferred to the Santa Clara county prison in San José neighbourhood (rated 2.4/5 stars on Google). It was not what he’d become used to. His daily diary entries talk of an overcrowded prison cell shared with twelve other detainees, most of them drug addicts. There was only one toilet and the water from the tap was brown. Baha’s skin was soon covered in rashes and boils. He wrote about his fears and how he joined one of the prison gangs to feel safer.

One year on, after a US judge granted extradition, three BKA agents come to collect him. On 13 April, 2015, they accompanied him to Frankfurt onboard Lufthansa flight 455. Returning to Germany for the first time in years, Baha had with him some lip balm, credit cards and his precious hand-written notes, amongst other items. And a special edition Audemars Piguet Royal Oak luxury watch, retail price approximately €60,000.

The trial 12 months later in a Cologne court lasted 14 days. All four defendants pleaded guilty. Baha’s evidence was helpful in securing convictions in the Deutsche Bank cases.

On 14 April, 2016, Baha himself was sentenced to five years and six months in jail on 47 counts of tax fraud, and of abetting tax fraud in another 22 cases. The German state was able to recover €5 million of the illicit gains run up by schemes involving companies controlled by Baha. That’s €5 million out of €40 million according to the indictment and against other estimates of up to €110 million.

The judge described the lenient sentence as appropriate given that Baha had shown himself to be cooperative and remorseful, and had been coerced into the crimes by others. The verdict stated that Baha was initially susceptible to financial inducement at a young age and later on was pressured into organized crime due to financial difficulties.

With two years in pre-trial detention, after just three months, Baha was once more a free man. German law enforcement is unsure of his current whereabouts. But Instagram provides a few clues as to how he has been enjoying his freedom, with selfies from the Champs-Elysées in Paris, safari trips in Kenya, New Year parties in Hong Kong and more nightlife in Las Vegas.

In all, Baha personally had effectively paid back €500,000 to the German state. His bank balance, it seems, is still sufficient to allow him the same kind of lifestyle he had during the peak years of his VAT carousel life of crime.

Become part of the story

We focus on long-term investigations. Your donation helps us to remain independent. Every little helps.

We keep you in the loop on our investigations. Subscribe to our English-language newsletter here for free.

Do you have information on tax fraud or other types of criminal activity? You can reach our journalist under marta.orosz@correctiv.orgor via or encrypted letter box.

Publications

by 30 European media

Information

Danish directors involved in VAT fraud that spans several EU countries

A large fraud worth millions of Euros by a criminal network including several Danish businessmen is being investigated by authorities in Europe and in the USA. The money appears to have been stolen in a VAT fraud with electricity that covers Norway, Poland, Germany, Slovenia, UK and Italy. The revelations are a result of a cross border investigation with Correctiv! And a network of journalists from several EU countries, the Danish newspapers Jyllands-Posten and Dagbladet Information. At the center of the fraud is the company Castor Energy, which was owned and operated by a group of Danish businessmen, but which had offices in several European countries. The directors used “missing traders” to steal of VAT from European treasuries. The VAT fraud case has connections to much broader investigation involving people in the US and Dubai.

Read the article

Jyllands Posten

Danish VAT fraud case with secret FBI investigation

For years, authorities in Europe and United States have investigated what seems to be a syndicate involving Danish citizens committing VAT fraud including the use of power trading. Millions of euros disappeared through a complicated series of transactions in Norway, Poland, Germany and Slovenia. We reveal how this case has ties to a possible fraud case in the US involving a secret FBI investigation into a much broader Danish network of persons residing in the US and Dubai.

Read the article

CORRECTIV

A multi-million teenage fraudster

The story of Amir B. shows how a clever teenager rose from mobile phone trader to tax carousel lynchpin within just a few years. Following his tracks reveals the structure of the fraud system and the difficulties the authorities face in the war against VAT fraud.

ZDF/Frontal 21

The big fraud

The biggest tax heist in history – fraudsters and terrorists are looting European tax coffers each year as European states fail to agree a common VAT system.

Read the article

Handelsblatt

Germany’s most dogged prosecutor

Handelsblatt met an insider who for many years was part of a VAT carousel fraud, providing insights into the scheme and its structures. Handelsblatt has also spoken to Marcus Paintinger, a prosecutor in the southern German city of Augsburg who has a reputation as the most dogged prosecutor in Germany. He is responsible for dozens of indictments and jail terms.

Read the article

Neo Magazin

Become a millionaire in months?

A tale made for satire: Jan Böhmermann explains how you can make millions while politicians fail to take the fraud seriously.

FAQ

The carousel explained in 100 seconds

Under the scheme, fraudsters claim the reimbursement of value-added tax (VAT) from the tax office that they never paid in the first place. VAT is supposed to be paid only by the final buyer of a product. Traders who pay VAT on the purchase of unfinished goods reclaim the tax paid from the tax office.

Fraudsters trade goods between EU member states several times and exploit the fact that no VAT is due on cross-border trades as member states have different VAT rates. If a fraudster based in Germany buys a car in France at zero percent VAT, he can sell it on to another trader in Germany with a 19 percent surcharge. He is obliged to pass this onto the tax office but instead keeps the money. By the time the tax office has noticed, the trader has disappeared, which is why he also called the missing trader, and this type of crime is also known as ‘Missing Trade Intra-Community’ (MTIC) fraud. Fraudsters mostly use expensive goods such as mobile phones or luxury cars, or virtual goods that can be traded without transport and storage costs such as emission certificates.

The EU Commission estimates the annual losses at €50 billion. In Germany, Europe’s largest economy, estimates range from€5 to €15 billion a year.

Only a fraction of the losses are ever recovered. Prosecuting VAT fraud takes years and in most cases only low-level operators are sentenced. The key players quickly move their illicit gains to off-shore accounts in tax havens, where the money is out of reach of European law enforcement.

50 BILLION

This much can be done with €50 billion

It’s hard to imagine what can be done with so much money.

Try for yourself!

THE COOPERATION

63 journalists – 35 newsrooms – 30 countries

Grand Theft Europe is an investigation by the German non-profit newsroom CORRECTIV, which in 2018 also coordinated the CumEx Files. The journalists again shared files and information to investigate the criminal networks. The participating newsrooms offer for the first time an overview on VAT carousel fraud across Europe.

Austria: Stefan Melichar (Addendum) Belgium: Lars Bové (De Tijd) Bulgaria: Rossen Bossev (Capital) Croatia: Anuška Delić, Mašenjka Bačić (Oštro) Cyprus: Yiannis Seitanidis (Politis) Czech Republic: Jiri Nadoba (RESPEKT) Denmark: Bo Elkjaer, Sebastian Gjerding, Lasse Skou Andersen (Information), Niels Sandoe, Matias Seidelin (Jyllands Posten) Estonia: Piret Reiljan (Äripäev) Finland: Magnus Berglund (YLE/MOT) France: Emmanuel Fansten, Jacques Pezet (Libération) Germany: Oliver Schröm (CORRECTIV), Marta Orosz (CORRECTIV), Christian Salewski (CORRECTIV), Anne-Lise Bouyer (CORRECTIV), Simon Wörpel (CORRECTIV), Ruth Fend (CORRECTIV), Frederik Richter (CORRECTIV), Corinna Cerruti (CORRECTIV), Hans Koberstein (ZDF Frontal 21), Markus Reichert (ZDF Frontal 21) René Bender (Handelsblatt), Jan Keuchel (Handelsblatt) Jean Peters (Neo Magazin Royale), Lisa Seemann (Neo Magazin Royale), Johannes Oberkrome (Neo Magazin Royale) Greece: John (Yannis) Souliotis, Tasos Telloglou (Kathimerini) Hungary: Blanka Zöldi (Direkt36, 444.hu) Italy: Giulio Rubino (CORRECTIV), Angelo Mincuzzi (IlSole24Ore) Latvia: Filips Lastovskis (Delfi) Lithuania: Liucija Zubrute (Verslo žinios), Vytautas V. Zeimantas (Verslo žinios) Luxembourg: Laurent Schmit (Reporter.lu) Malta: Caroline Muscat (The Shift) Netherlands: Eric Smit (Follow the Money), Robert Kosters (Follow the Money), Dennis Mijnheer (Follow the Money) Norway: Jan Gunnar Furuly (Aftenposten) Poland: Wojciech Cieśla (Fundacja Reporterow), Anna Kiedrzynek (Newsweek) Portugal: Elisabete Miranda (Expresso) Romania: Razvan Lutac (Libertatea), Laura Stefanut (Libertatea) Slovakia: Peter Sabo (Aktuality.sk) Slovenia: Anuška Delić (Oštro), Klara Škrinjar (Oštro) Spain: Olaya Argueso (CORRECTIV), María Zuil (El Confidencial) Sweden: Emelie Rosen (Sverige Radio) Switzerland: Sylke Gruhnwald (Republik), Marguerite Meyer (Republik) UK: Madlen Davies (The Bureau of Investigative Journalism), Ben Stockton (The Bureau of Investigative Journalism)

Belgien: Lars Bové (De Tijd) Bulgarien: Rossen Bossev (Capital) Dänemark: Bo Elkjaer (Information), Sebastian Gjerding (Information), Lasse Skou Andersen (Information), Niels Sandoe (Jyllands Posten), Matias Seidelin (Jyllands Posten) Deutschland: Oliver Schröm (CORRECTIV), Marta Orosz (CORRECTIV), Christian Salewski (CORRECTIV), Anne-Lise Bouyer (CORRECTIV), Simon Woerpel (CORRECTIV), Ruth Fend (CORRECTIV), Frederik Richter (CORRECTIV), Corinna Cerruti (CORRECTIV), Hans Koberstein (ZDF Frontal 21), Markus Reichert (ZDF Frontal 21), René Bender (Handelsblatt), Jan Keuchel (Handelsblatt), Jean Peters (Neo Magazin), Lisa Seemann (Neo Magazin), Johannes Oberkrome (Neo Magazin) Estland: Piret Reiljan (Äripäev) Finnland: Magnus Berglund (YLE/MOT) Frankreich: Emmanuel Fansten (Libération), Jacques Pezet (Libération) Griechenland: John (Yannis) Souliotis (Kathimerini), Tasos Telloglou (Kathimerini) Italien: Giulio Rubino (CORRECTIV), Angelo Mincuzzi (IlSole24Ore) Kroatien: Anuška Delić (Oštro), Mašenjka Bačić (Oštro) Lettland: Filips Lastovskis (Delfi) Litauen: Liucija Zubrute (Verslo žinios), Vytautas V. Zeimantas (Verslo žinios) Luxembourg: Laurent Schmit (Reporter.lu) Malta: Caroline Muscat (The Shift) Niederlande: Eric Smit (Follow the Money), Robert Kosters (Follow the Money), Dennis Mijnheer (Follow the Money) Norwegen: Jan Gunnar Furuly (Aftenposten) Österreich: Stefan Melichar (Addendum) Polen: Wojciech Cieśla (Fundacja Reporterow), Anna Kiedrzynek (Fundacja Reporterow) Portugal: Elisabete Miranda (Expresso) Rumänien: Razvan Lutac (Libertatea), Laura Stefanut (Libertatea) Schweden: Emelie Rosen (Sverige Radio) Schweiz: Sylke Gruhnwald (Republik) , Marguerite Meyer (Republik) Slowakei: Peter Sabo (Aktuality.sk) Slowenien: Anuška Delić (Oštro), Klara Škrinjar (Oštro) Spanien: Olaya Argueso (CORRECTIV), María Zuil (El Confidencial) Tschechien: Jiri Nadoba (RESPEKT) Ungarn: Blanka Zöldi (Direkt36, 444.hu) Vereinigtes Königreich: Madlen Davies (The Bureau of Investigative Journalism), Ben Stockton (The Bureau of Investigative Journalism) Zypern: Yiannis Seitanidis (Politis)tanidis (Politis)

CORRECTIV

Investigative. Independent. Non-profit.

CORRECTIV is the first non-profit newsroom in the German-speaking region. We investigate crime, injustice and abuse of power. CORRECTIV is financed by donations.

An investigation by CORRECTIV

Project Management: Marta Orosz (head), Christian Salewski, Oliver Schröm

Investigation: Marta Orosz, Hans Koberstein, Markus Reichert, David Crawford

Writing: Ruth Fend, Oliver Schröm

Design: Benjamin Schubert

Joint investigation platform, data & infrastructure: Anne-Lise Bouyer, Simon Wörpel

Pictures: Ivo Mayr

Visualisation: Simon Wörpel, Anne-Lise Bouyer, Corinna Cerruti

Development: Benjamin Schubert, Michel Penke

Contributions: Corinna Cerruti, Marius Wolf

Social Media: Luise Lange, Katharina Späth, Valentin Zick, Corinna Cerutti

Animation Video: Daniel Schleusner

Trailer Video: Benjamin Schubert, Simon Wörpel

English-language production: Frederik Richter

Photo credits: Karan Bhatia / unsplash, Camera Press / Picture Press, Michael Fenton / unsplash, Frontal 21/ZDF, Romeo Gacad / AFP, Daniel Leal-Olivas / AFP, Ivo Mayr / CORRECTIV, Giulio Napolitano / AFP, David Rodrigo / unsplash, Boris Roessler / dpa, Daniel Roland / AFP, Ant Rozetsky / unsplash, John Thys / AFP, Patrick Tomasso / unsplash, Romain V / unsplash

May 7th 2019